0502 - Ed Wheatley

Ed Wheatley is the vice president of the St. Louis chapter of the Society for American Baseball Research, an award-winning author of multiple baseball books, and an Emmy Award-winning filmmaker. During our conversation, he referenced a handful of things and people upon which you may want to do more research. Consider this page to be your “liner notes” for the episode so you can follow along.

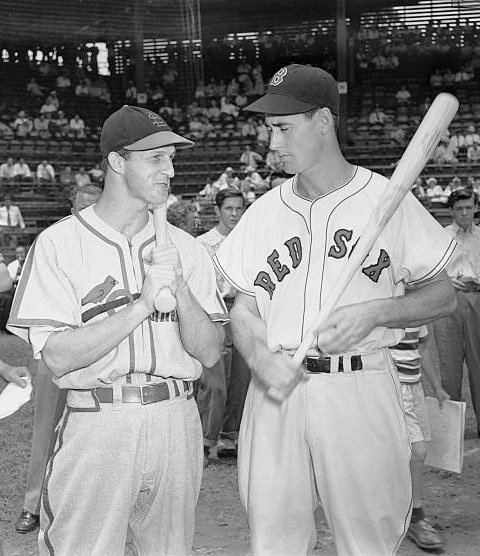

Me and Ed Wheatley after recording our interview in his home near St. Louis.

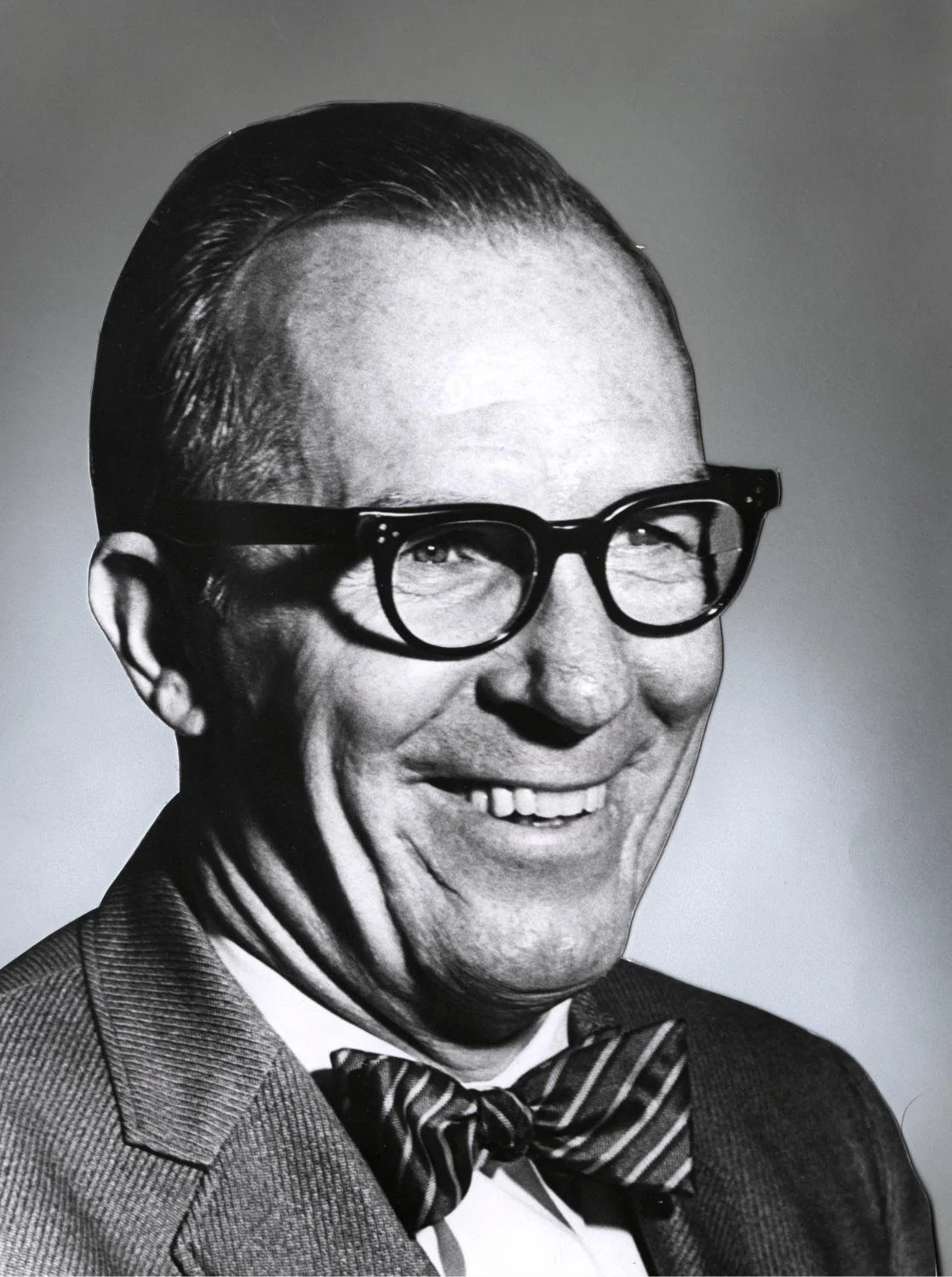

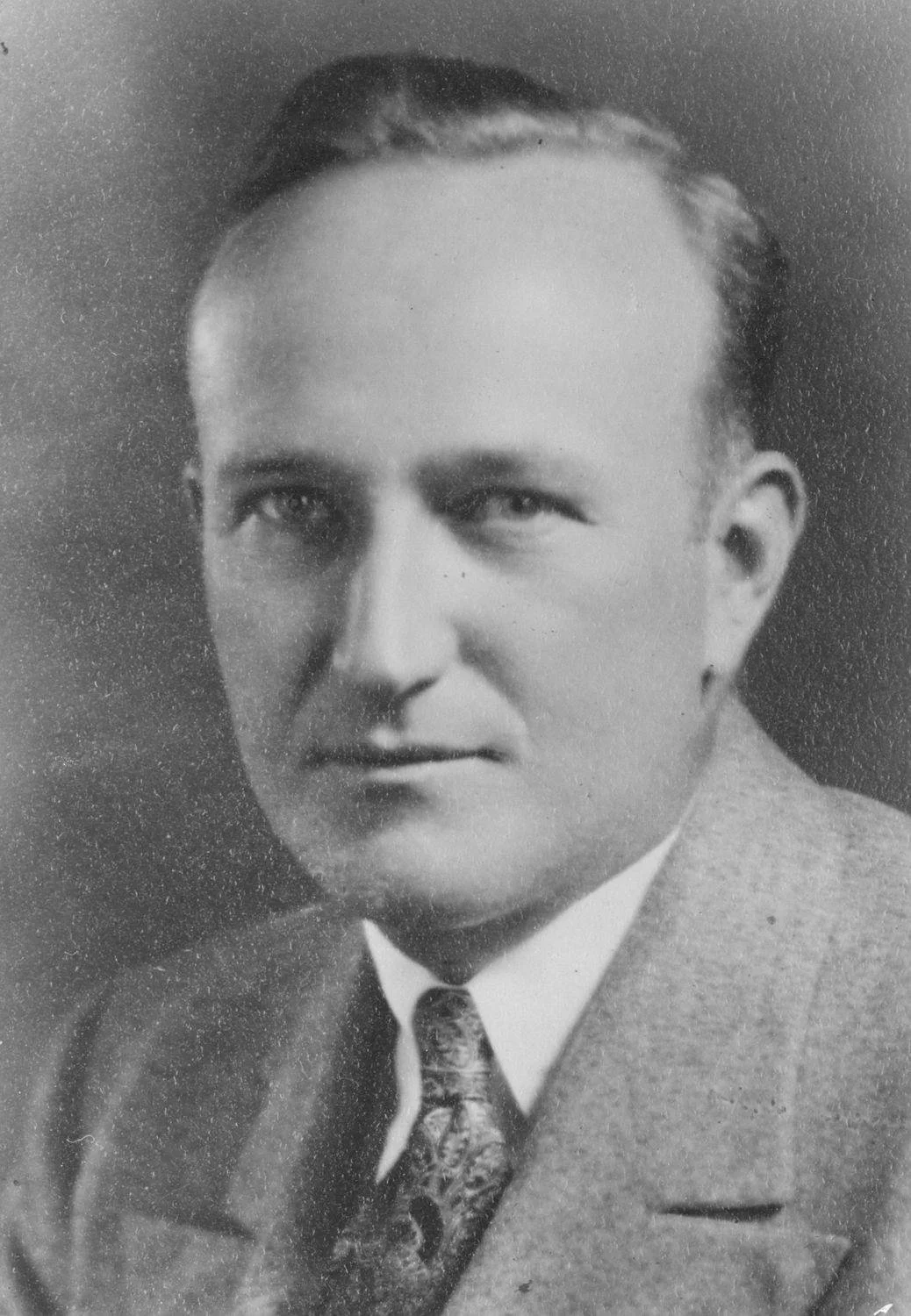

Ed Wheatley

Ed Wheatley is a St. Louis Cardinals fan and historian, and an award-winning author of multiple baseball books. He is also a filmmaker who has produced three films, with each of them receiving EMMY Award nominations, as well as a win in 2020.

Bob Broeg

Bob Broeg was a titan of sports writing and knowledge in St. Louis for six decades. He was a local boy through and through, growing up in south city, attending the University of Missouri, and working in St. Louis (aside from a very brief time early in his career in Boston), from 1946 until his death.

He held his dream job, St. Louis Cardinals beat writer, at the St. Louis Post-Dispatch, before being promoted to sports editor, and then to assistant to the publisher.

The St. Louis chapter of the Society for American Baseball Research bears his name.

Greater St. Louis Amateur Baseball Hall of Fame

Ed is an inductee in the Greater St. Louis Amateur Baseball Hall of Fame, being honored as a Contributor in the Class of 2023. With his induction, Ed joined his father, Ed Wheatley, Sr., who had been honored as a Player in the Class of 1989.

St. Louis Browns: The Story of a Beloved Team

Ed’s book, St. Louis Browns: The Story of a Beloved Team, was Sports Collectors Digest’s selection as the best baseball book in 2017. It was also nominated for the Lawrence Ritter Award by the Society for American Baseball Research for the best baseball book of 2017, and is #45 on Book Authority’s list of 100 Best Baseball Books of All Time.

You can BUY IT HERE.

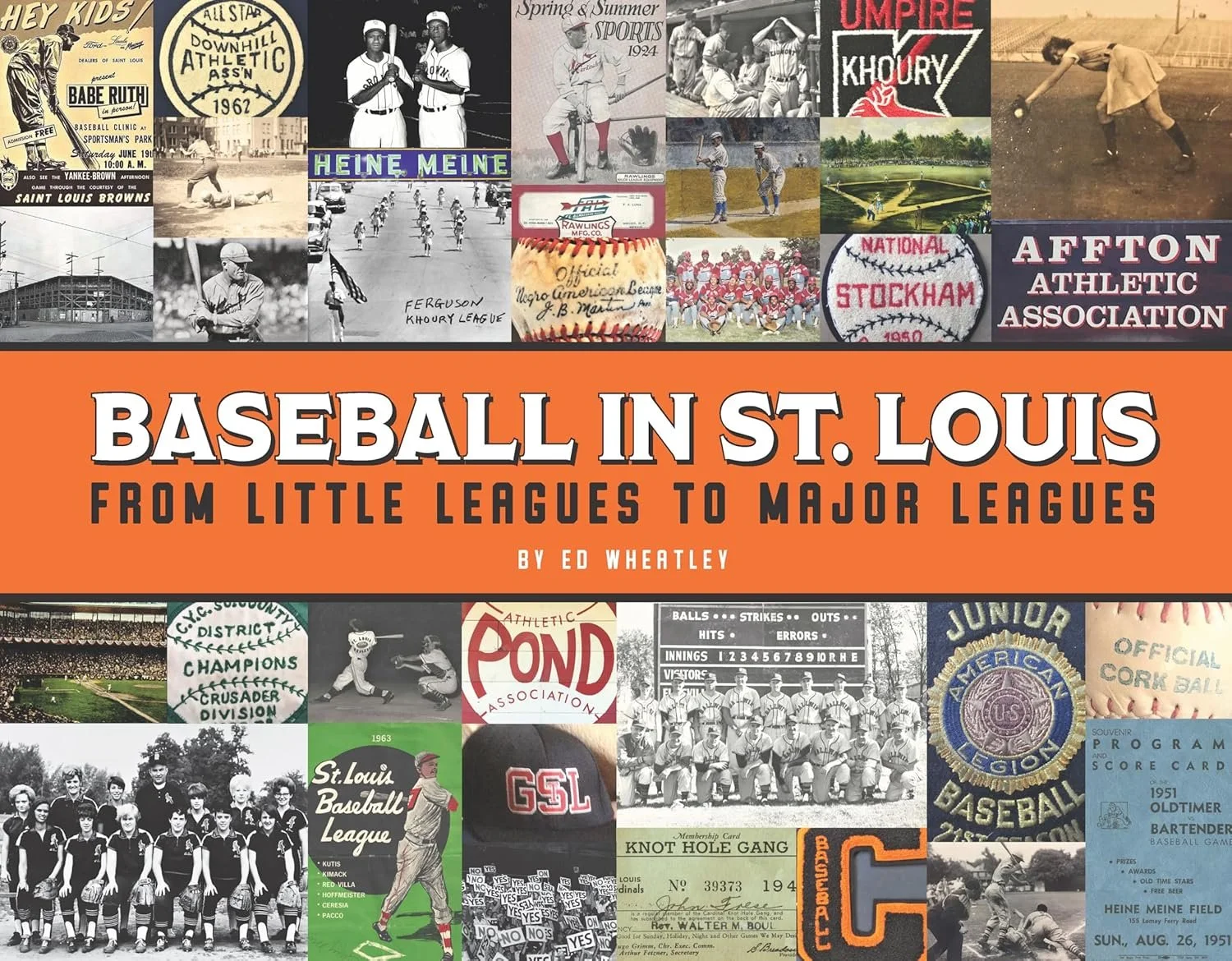

Baseball in St. Louis: From Little Leagues to Major Leagues

Ed’s book, Baseball in St. Louis: From Little Leagues to Major Leagues, was selected by the St. Louis Post-Dispatch as one of the top 25 books of 2020 , and is #73 on Book Authority’s list of 100 Best Baseball Books of All Time.

You can BUY IT HERE.

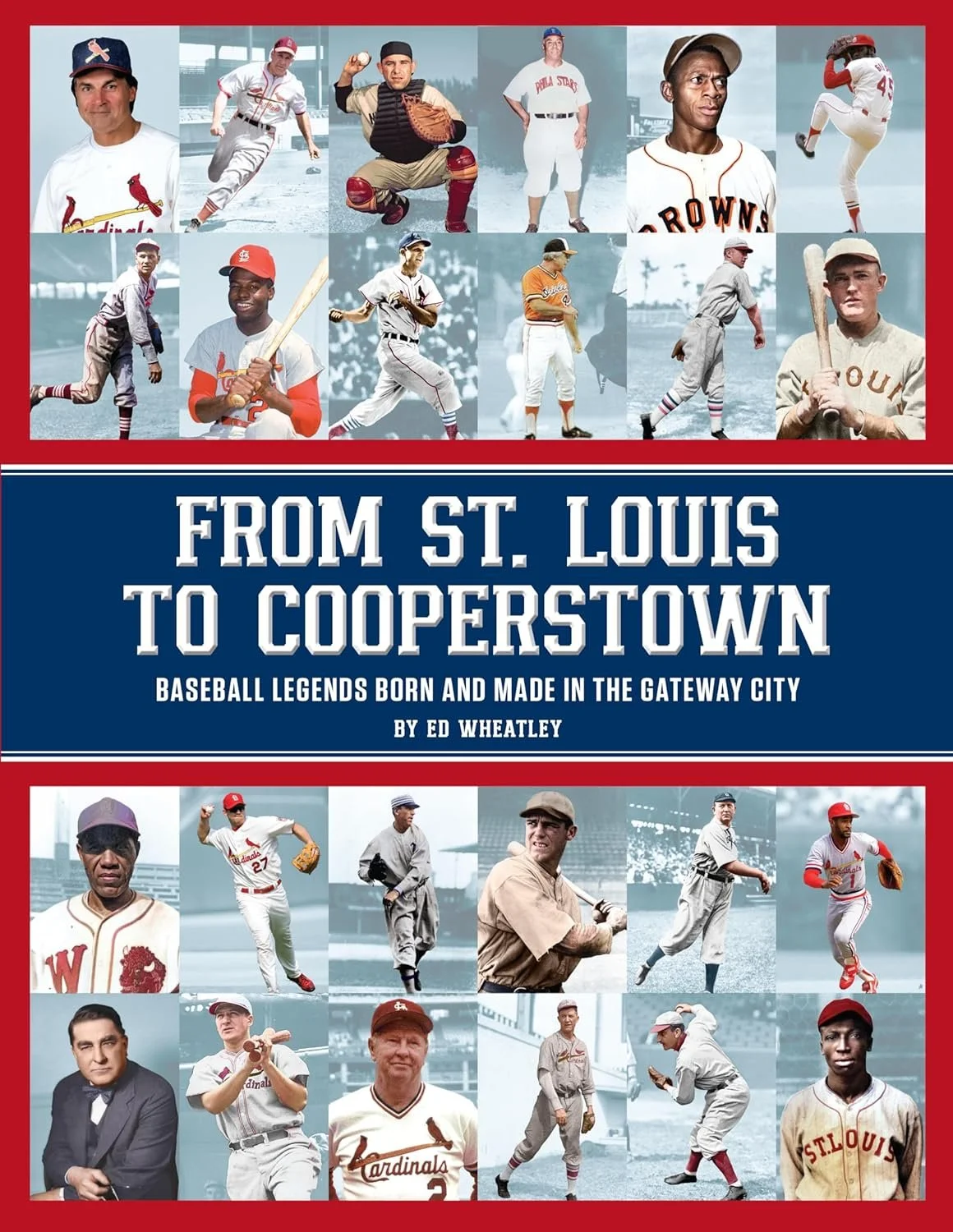

From St. Louis to Cooperstown: Baseball Legends Born and Made in the Gateway City

Ed’s most recent book, From St. Louis to Cooperstown: Baseball Legends Born and Made in the Gateway City, came out in May of 2025 and walks us through the chronology of the city’s baseball history, detailing the moments each player had on their road from St. Louis to Cooperstown.

You can BUY IT HERE.

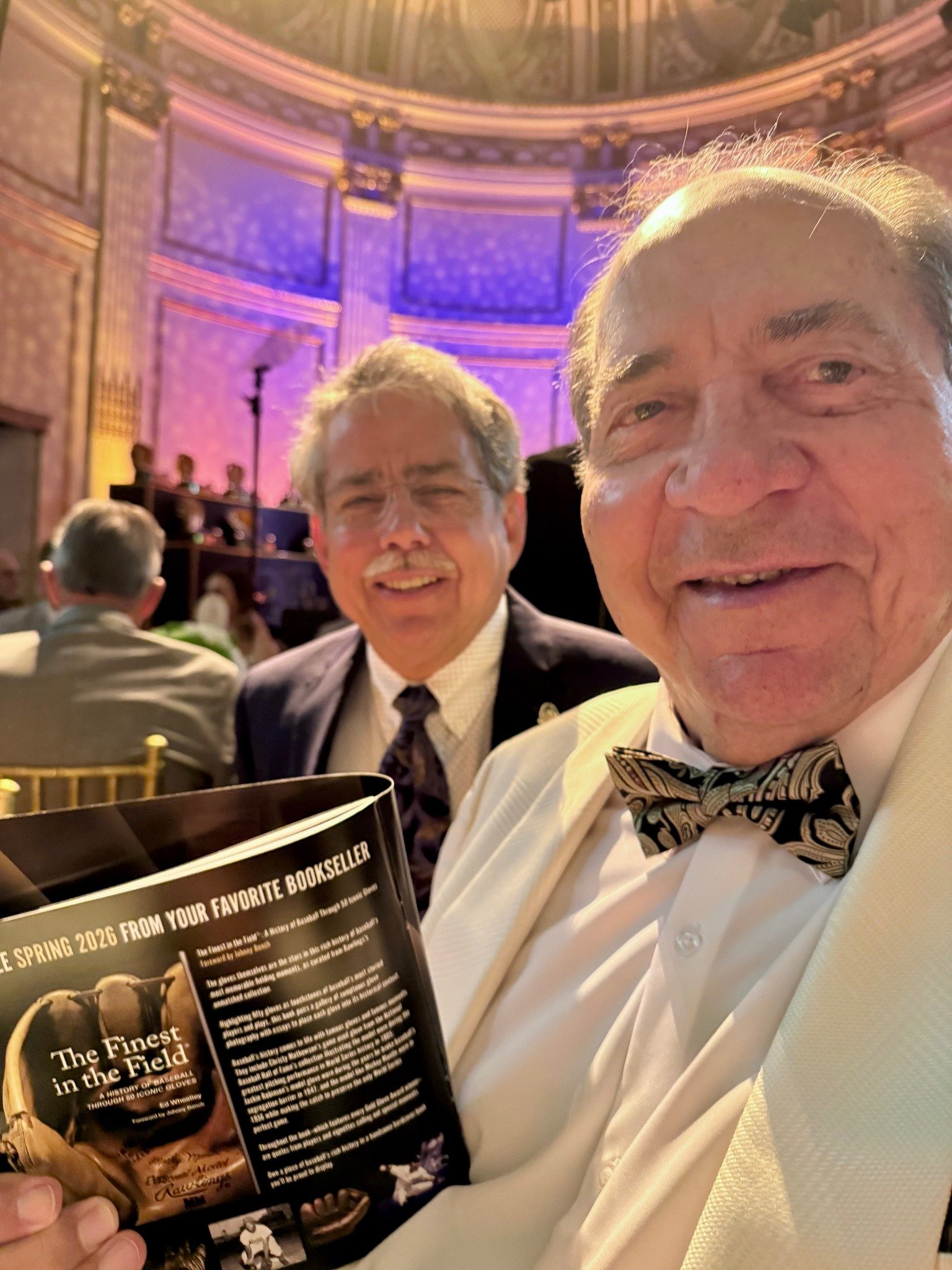

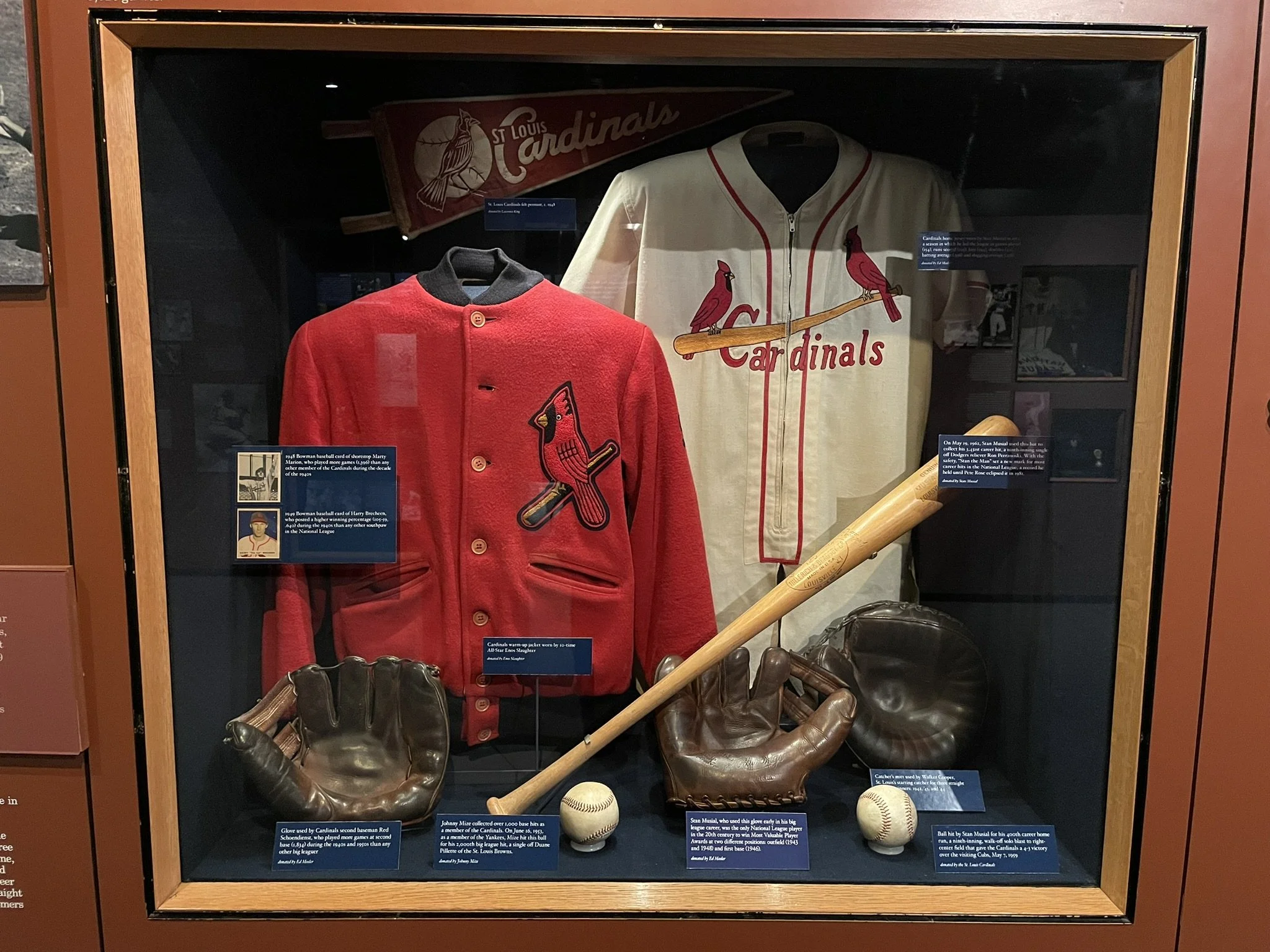

The Finest in the Field®: A History of Baseball Through 50 Iconic Gloves

Ed’s next book is a collaboration with Rawlings which is set to be released in April of 2026.

It is called The Finest in the Field®: A History of Baseball Through 50 Iconic Gloves, which highlights fifty gloves as touchstones of baseball’s most storied players and plays.

It will pair a gallery of sumptuous glove photography with essays, archival photos of the players, period advertisements, and other memorabilia to place each glove into its proper historical context.

You can BUY IT HERE.

World Series Wins

The Cardinals have won 19 National League pennants, which is third most in history behind the Dodgers and Giants. Their 7 National League Championship Series victories trail only the Dodgers, who have won the NLCS 10 times.

The Cardinals have won 11 World Series titles, which is the most of any team in the National League, and second most in history, behind the Yankees.

The Cardinal Way

“From practice drills to roster management, The Cardinal Way has been used to describe everything that the St. Louis Cardinals organization does and why they do it. It has served as a conduit through which the organization has blended the philosophies of all its past and present managers and coaches. This blend has even helped mend organizational schisms between the management of the Major League club and the overall development of the minor league system.” - Kyle Thompson, MLB.com

George Kissell

George Kissell was a minor league player, manager, coach, scout, and instructor, as well as a Major League coach for the St. Louis Cardinals organization, and a key in establishing The Cardinal Way.

Kissell summarized the reason for The Cardinal Way best: "Tell me and I'll forget. Show me and I'll remember. Involve me and I'll understand."

Dave Ricketts

Dave Ricketts was a catcher and coach who played parts of six seasons (1963, 1965, 1967–1970) with the St. Louis Cardinals and Pittsburgh Pirates.

Ricketts was a reserve catcher on the 1967 World Series champion Cardinals and their 1968 pennant winners. He later served as a longtime bullpen coach of the Cardinals (1974–1975, 1978–1991), including their 1982 World Series champions and 1985 and 1987 pennant winners, after having been the bullpen coach for the Pirates from 1971 to 1973, including the 1971 World Series champions.

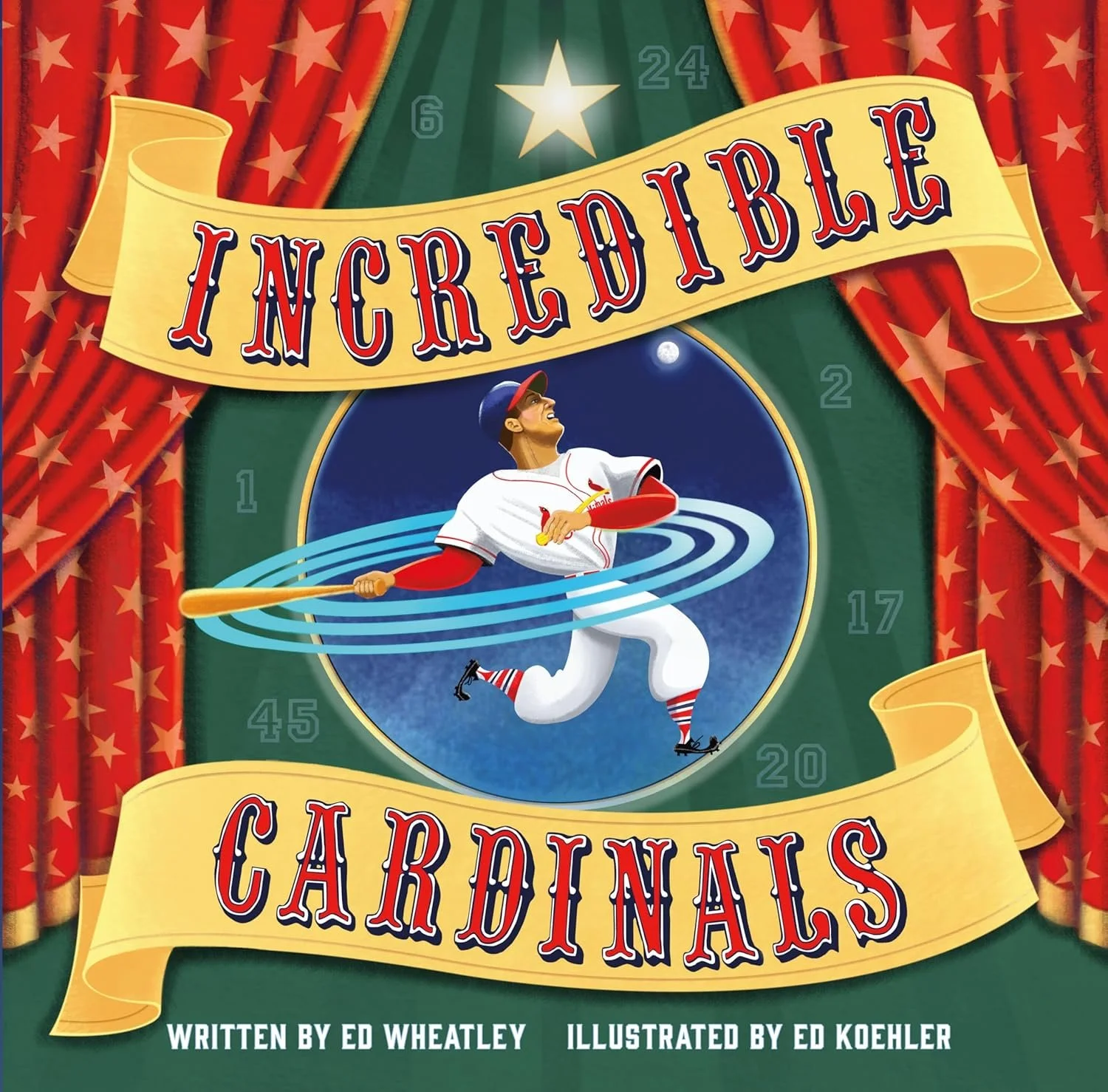

Incredible Cardinals

Ed’s book, Incredible Cardinals, came out in 2018 and discusses each of the 14 individuals who have had their number retired by the Cardinals organization.

You can BUY IT HERE.

Beaumont High School

Ed’s dad, Edward R. Wheatley, Sr., played ball at Beaumont High School in St. Louis, which produced a number of professional baseball players in the 1940s and 1950s.

Whitey Herzog

Whitey Herzog made his major league debut as a player in 1956 with the Washington Senators. After his playing career ended in 1963, Herzog went on to perform a variety of roles in Major League Baseball, including scout, manager, coach, general manager, and farm system director.

As a scout and farm system director, Herzog helped the New York Mets win the 1969 World Series. As a big-league manager, he led the Kansas City Royals to three consecutive playoff appearances from 1976 to 1978.

Hired by Gussie Busch in 1980 to helm the St. Louis Cardinals, the team made three World Series appearances, winning the 1982 World Series over the Milwaukee Brewers and falling in 1985 and 1987.

Semi-Pro League

In the 1950s and 1960s, St. Louis had one of the premier semi-pro leagues in the country, thanks to the vast amount of talent and decades of teaching that had gone into the area.

As a little kid, Ed was a bat boy for his dad’s teams in those leagues. It was during these years, being around ex-major leaguers and future stars, when Ed truly developed his love of the game.

1951 & 1952 Fon du Lac Panthers

Ed’s dad batted .260 with 112 walks, 90 RBI, and 104 runs in 153 games for the Yankees’ Class D Fon du Lac Panthers over 153 games in 1951 and 1952. He played briefly for the Joplin Miners in 1953, which is a team Mickey Mantle had played for in 1950.

Stockham Post 245

The 1956 Fred W. Stockham Post 245 team won the championship.

Players from Beaumont and Central High Schools began playing together on the same Legion team for the first time that season. Beaumont was coming off a Missouri state high school title, while Central previously had won three consecutive state titles.

Minor League Systems

In the 1940s and 1950s, the minor league system was much different from what it is today. Some teams had dozens of farm teams, meaning you had to beat out hundreds of other prospects if you wanted a chance at the big league club.

Here, Brooklyn Dodgers prospects do some running at Dodgertown in Vero Beach, Florida in 1948.

Photo courtesy of the George Silk The LIFE Picture Collection/Shutterstock

Senior League

Ed plays baseball to this day, in competitive senior leagues which travel all over the country.

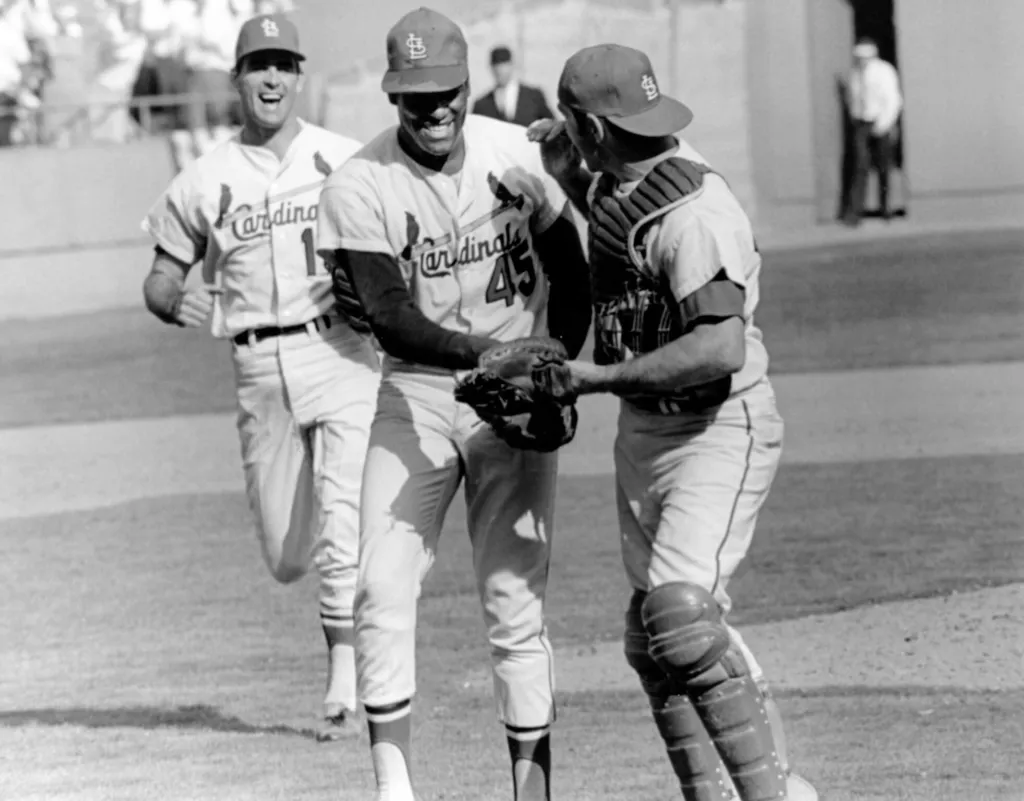

1964 World Series

The 61st edition of the World Series matched the National League champion Cardinals against the American League champion Yankees.

St. Louis won in seven games, giving the Cardinals their seventh world championship.

The Yankees, who had appeared in 15 of 18 World Series since 1947, would not play in the Series again until 1976.

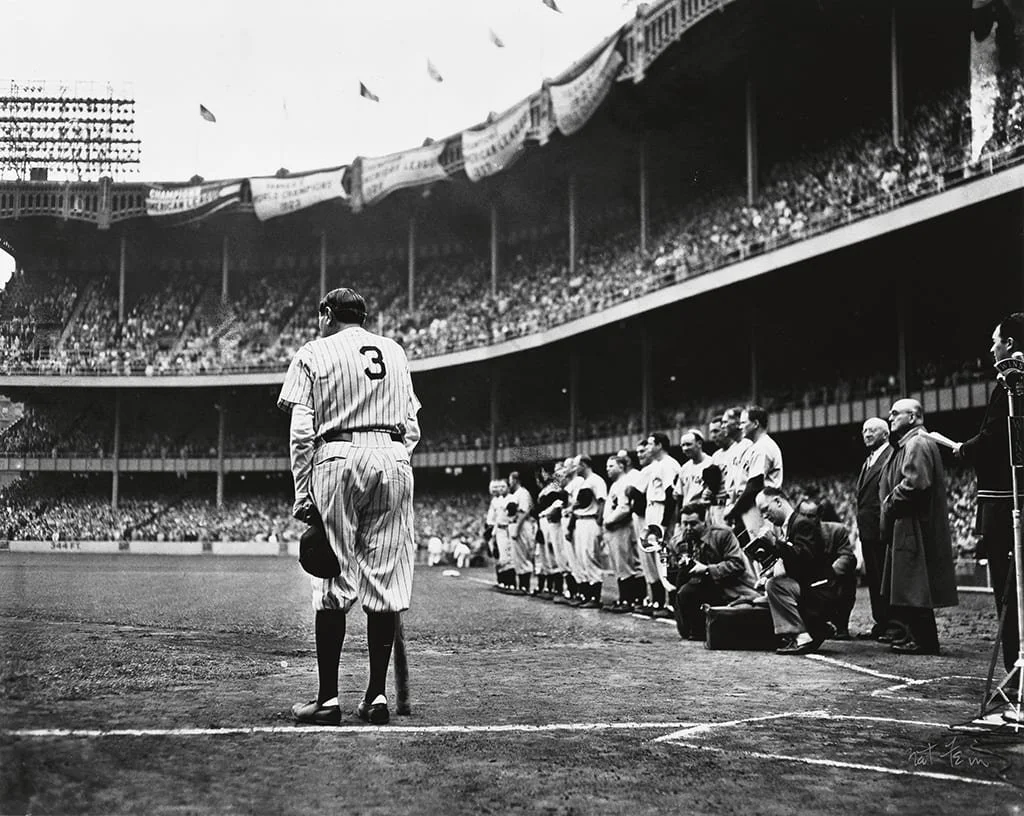

Babe Bows Out

Nat Fein’s photo of Babe Ruth from what many believed would be Babe’s final public appearance on June 13 of 1948 is one of the lasting images of the sport’s greatest hero.

“Babe Bows Out” won Fein the Pulitzer Prize.

“I saw Ruth standing there with his uniform, No. 3 . . . and knew that was the shot. It was a dull day, and most photographers were using flash bulbs, but I slowed the shutter and took the picture without a flash.”

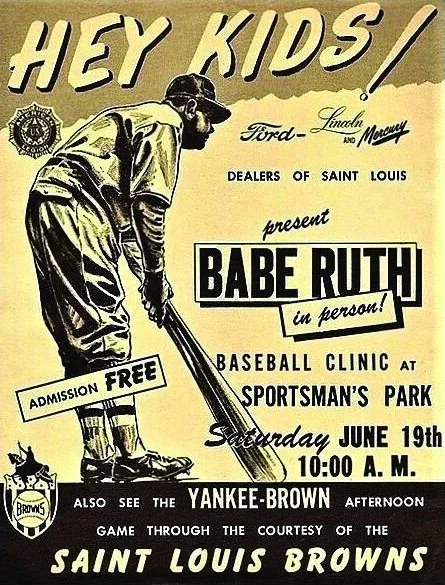

Babe’s Actual Last Appearance At a Major League Stadium

While many people think that Babe Ruth’s final appearance at a Major League stadium was June 13, 1948 at Yankee Stadium, they are mistaken. Babe’s actual last appearance at a Major League stadium came six days later, at Sportsman’s Park in St. Louis, as Babe continued his tour across the country promoting American Legion ball.

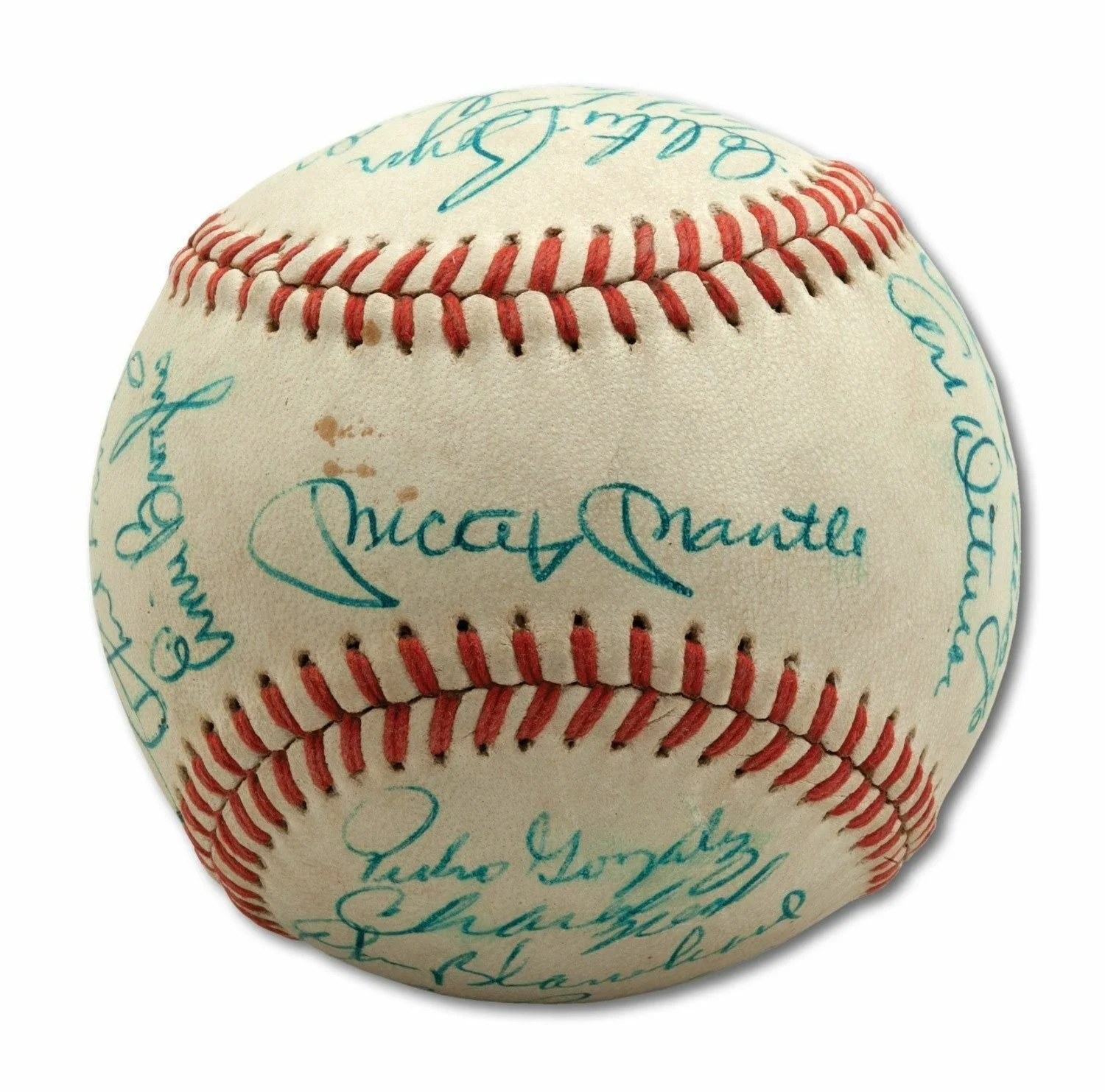

Signed Baseball

Babe gave each player from the American Legion teams an autographed baseball, so Ed’s dad got one that day. 75+ years later, Ed now has that ball in his possession, despite bringing it to school growing up for one of the most expensive versions of “Show And Tell” ever.

Luckily, Ed and his classmates didn’t have a Sandlot moment with the ball…

How Quickly They Forget

Ed speaks at a lot of schools in the St. Louis area, and he is surprised to see how few kids today know who Stan Musial was.

Maybe Ed is a tad biased, because Stan was his favorite player growing up, but it just goes to show you how time marches on.

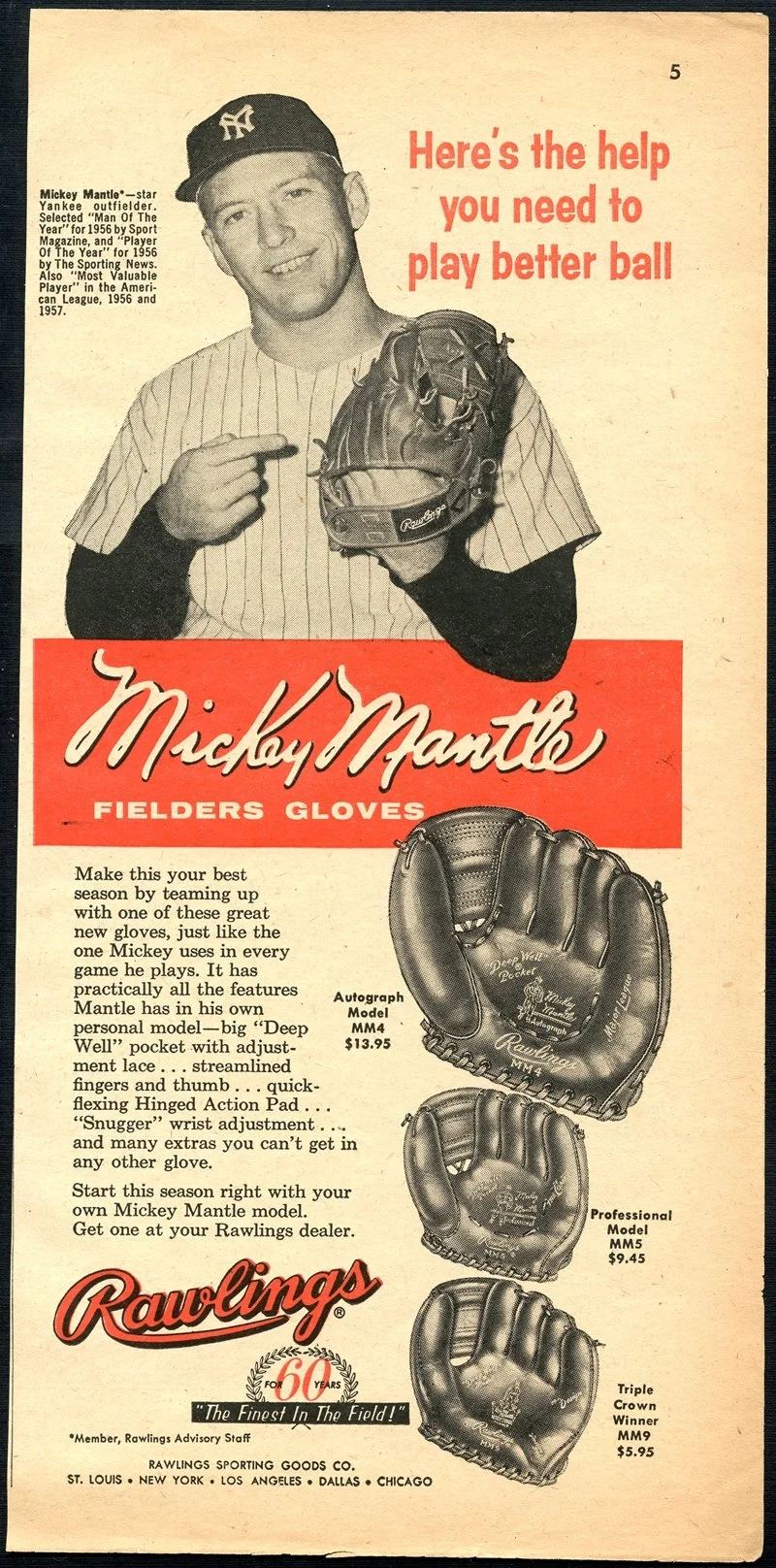

Mickey Mantle’s Signature

Mickey’s signature is magical. His autograph is one of the most coveted signatures in the hobby. Collector and historian Kelly Eisenhauer put together this incredible article for Sports Collectors Digest with dozens of examples of Mickey’s signature throughout the years, showing the major (and minor) changes over time.

I urge you to actually go read the article and see all of the different examples Kelly put together to show the decades of change in Mickey’s signature.

If you’re new the to show, you may have missed Episode 7 of Season 4, which was a discussion with Tom Catal, who is Mickey Mantle’s former autograph agent, and was the founder and curator of the Mickey Mantle Museum in Cooperstown, New York. We talk about the different changes in Mickey’s signature over time, and cover many other incredible topics.

Mickey’s 1964 Signature

Winning 99 regular-season games, the 1964 New York Yankees were the last edition of the great Bronx dynasty that could trace its origins back to the 1947 season.

Even though the team had some fresh blood in the likes of pitcher Jim Bouton and first baseman Joe Pepitone, the team was top heavy with aging stars such as Mickey Mantle and Whitey Ford.

Though they lost in seven games to the Cardinals in the World Series, the 1964 Yankees were still the top A.L. team that year.

Rawlings

Ed knows what he’s talking about when it comes to the different signatures on a Mickey Mantle autograph model glove and a Mickey Mantle signed baseball, because his current project (set to be released in April of 2026) is a book with Rawlings about 50 of the most significant baseball gloves in history.

You can BUY IT HERE.

Elston Howard

Aside from Stan Musial, Ed’s favorite player growing up was Elston Howard. Elston Howard was a catcher and a left fielder during a 14-year career from 1948 through 1968 which saw him play in the Negro leagues and Major League Baseball, primarily for the New York Yankees. A 12-time All-Star, he also played for the Kansas City Monarchs and the Boston Red Sox.

In 1955, he was the first African American player on the Yankees roster, eight years after Jackie Robinson had broken MLB's color barrier in 1947. Howard was named the American League's Most Valuable Player for the 1963 pennant winners after finishing third in the league in slugging percentage and fifth in home runs, becoming the first black player in AL history to win the honor.

He won Gold Glove Awards in 1963 and 1964, in the latter season setting AL records for putouts and total chances in a season.

Roger Maris

And aside from Elston Howard, Ed’s other favorite player was Roger Maris. Maris is best known for setting a new MLB single-season home run record with 61 home runs in 1961, but he also appeared in seven World Series, playing for Yankees teams that won the World Series in 1961 and 1962, and for a Cardinals team that won the World Series in 1967.

Maris made his major league debut for the Cleveland Indians in 1957. He was traded to the Kansas City Athletics during the 1958 season, and to the New York Yankees after the 1959 season. Maris finished his playing career as a member of the St. Louis Cardinals in 1967 and 1968. Maris was an AL All-Star from 1959 through 1962, the AL MVP in 1960 and 1961, and an AL Gold Glove Award winner in 1960.

Ed’s Own Playing Career

Ed has played in tournaments all over the country, from the Midwest, to Florida, to North Carolina.

Ed has played with and against players from all over the world, including former Major League players, former Minor League players, and former college players.

Ed’s teams have played against teams from all over the world, including Canada, Puerto Rico, the Dominican Republic, and Venezuela.

The Original Green Monster

When the Red Sox renovated the Green Monster at Fenway Park to put seating on top of it, they took the original wall and sent it down to their minor league stadium in Florida. That’s one of the places Ed’s team plays in a tournament, which is always a thrill for him.

Terry Park

The Terry Park Ballfield (also known as the Park T. Pigott Memorial Stadium) in Fort Myers, Florida hosted Major League Baseball spring training for years, as well as a dozen years of Florida State League baseball. The stadium has hosted the Philadelphia Athletics, Cleveland Indians, Pittsburgh Pirates, and Kansas City Royals spring training needs throughout the years.

Babe Ruth, Lou Gehrig, Ty Cobb, Roberto Clemente, Jimmy Foxx, Bob Feller, Tris Speaker, and George Brett are some of the Hall of Famers who have played at Terry Park, but Ed especially loves walking in the footsteps of George Sisler.

Fearless

While the level of play in Ed’s senior leagues is very competitive, he shows no fear on the mound. After all, how could he, when he’s thrown to Ozzie Smith before?

Baseball in St. Louis

There have been dozens of genuinely great Major League players who have come out of the St. Louis area over the years, including more than a handful Hall of Famers.

Ed talks about St. Louis’ rich baseball history in his book, Baseball in St. Louis: From Little Leagues to Major Leagues.

You can BUY IT HERE.

Rick Hummel

Rick Hummel, nicknamed the “Commish”, covered the Cardinals for the St. Louis Post-Dispatch for 50 years before retiring after the 2022 season.

The Busch Stadium Press Box is named after both Rick and Hall of Fame writer Bob Broeg, who also covered the Cardinals for the Post-Dispatch.

J. Roy Stockton

J. Roy Stockton was a sportswriter who covered the Cardinals from 1915 to 1958, mostly for the St. Louis Post-Dispatch. In addition to his newspaper work, Stockton wrote several books, had a weekly radio show, served as president of the Florida State League, and was a member of the Veterans Committee of the Hall of Fame.

Shortly before his death in 1972, he was honored by the Hall of Fame with the J.G. Taylor Spink Award

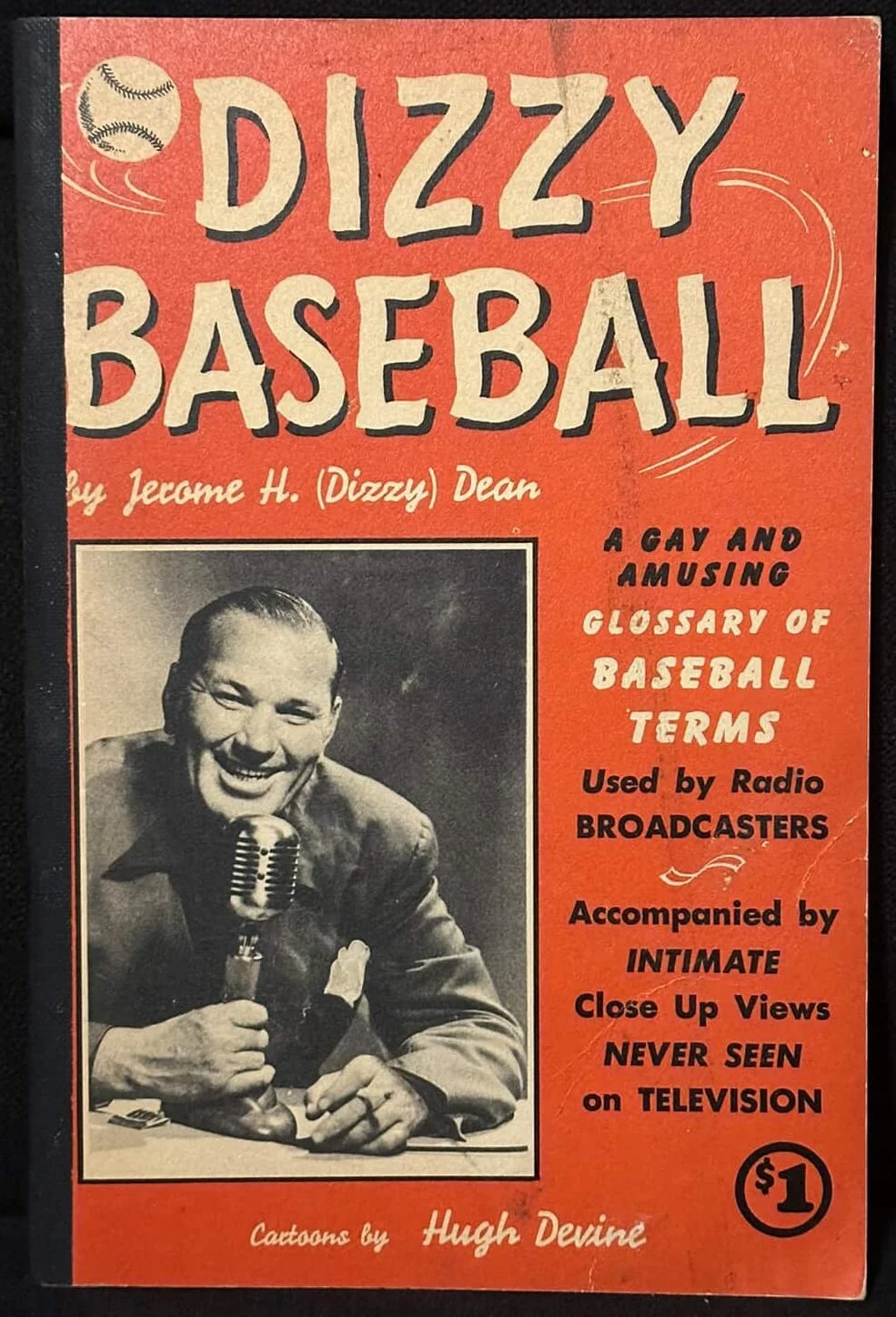

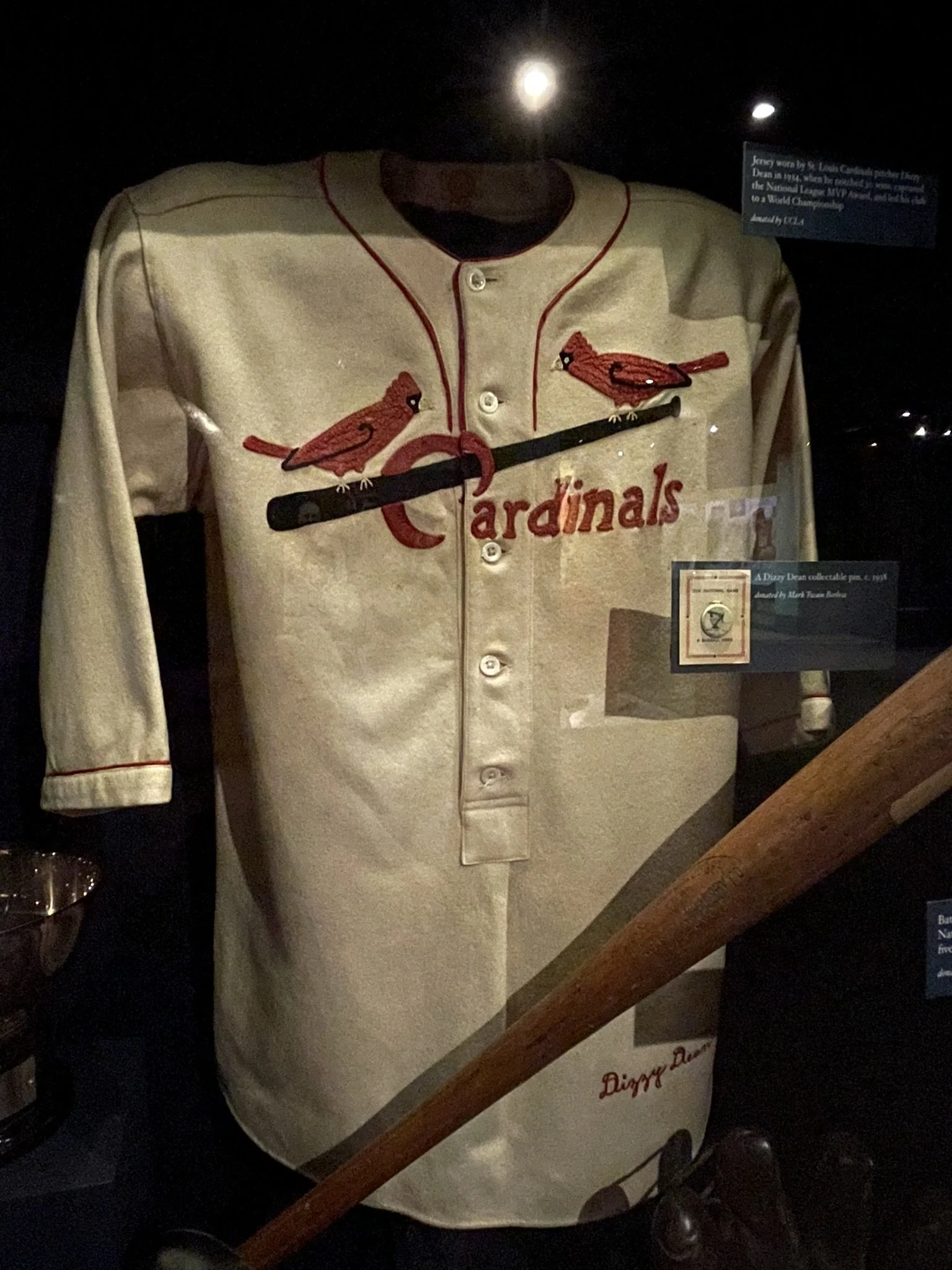

Dizzy Dean

As a radio announcer, Dizzy Dean earned a devoted following and some enemies. He broke into song, usually "The Wabash Cannonball," during dull games, and his neologisms and malapropisms, such as "He slud into third" and "The players returned to their respectable bases," became legendary.

In 1946 two Missouri schoolteachers complained to the Federal Communications Commission that Dean's broadcasts were "replete with errors in grammar and syntax" and were "having a bad effect on their pupils."

Norman Cousins of the Saturday Review of Literature was among those who rallied to Dean's defense, and Dizzy himself offered something of an apology. "Maybe I am butcherin' up the English language a little," he said. "Well, all I got to say is that when me and Paul and pa was pickin' cotton in Arkansas, we didn't have no chance to go to school much. But I'm glad that kids are gettin' that chance today."

September 28, 1947

A crowd of 15,910 attended Sportsman’s Park on September 28, 1947 to see 37-year-old Dizzy Dean face off against the White Sox. It would be the second-highest attendance the Browns would have all season.

Dean pitched three innings without allowing a run, scattering three hits and walking one batter. In bottom of the third, Dean also hit a single! However, he pulled a muscle on the hit and left after pitching the fourth inning.

Dizzy’s Injury

This injury, more than 10 years before his appearance for the Browns, would be the beginning of the end for Dizzy as a pitcher in the Major Leagues.

Harry Caray

Harry Caray caught his break when he landed a job with the National League St. Louis Cardinals in 1945 and, according to several histories of the franchise, proved as adept at selling the sponsor's beer as at the play-by-play description.

Caray teamed with former major-league catcher Gabby Street to call Cardinals games through 1950, as well as those of the American League St. Louis Browns in 1945 and 1946.

Caray’s subsequent partners in the Cardinals' booth included Stretch Miller, Gus Mancuso, Milo Hamilton, Joe Garagiola, and Jack Buck.

Jack Buck

Jack Buck was one of Missouri’s sports broadcasting pioneers. In 1954 Buck was hired by KMOX in St. Louis to be a member of the famous St. Louis Cardinals broadcasting team alongside Harry Caray, Milo Hamilton, and Joe Garagiola. As the main play-by-play announcer for KMOX radio, Buck was known as the “Voice of the St. Louis Cardinals” for nearly half a century.

He was also a nationally recognized television and radio announcer who covered games for the National Football League, the National Hockey League, and the National Basketball Association. In all, Buck called seventeen Super Bowls and eight World Series and was inducted into numerous sports broadcasting halls of fame.

Cardinal Nation

What started out because of KMOX’s incredibly strong radio signal has become a tradition now multiple generations old: listening to the Cardinals on the radio, even if you live hundreds of miles away from St. Louis.

Bob Costas

Bob Costas once told Ed that he used to go sit in his dad’s car as a kid and listen to Cardinals games on the radio.

KMOX

Partners in a great tradition … the Cardinals and the Voice of St. Louis (and beyond).

Union Printers National Baseball League

As early as 1883, union printers in New York City had organized the New York Morning Newspaper Baseball League with teams representing different New York and Brooklyn newspapers. The first Union Printers National Baseball League Tournament took place in New York City in September of 1908.

Sponsored each year by the International Typographical Union (ITU), the tournament brought together teams representing the ITU from different cities for several days of sports, camaraderie, and brotherhood.

3,000,000+ Fans

From the Home Run Race summer of 1998 through 2019, the final normal regular season before COVID, the Cardinals drew 3 million or more fans in 21 of the 22 seasons. The only season in that span during which they didn’t reach 3 million was 2003, when they still drew 2.9 million.

Brown Stockings

The St. Louis Brown Stockings entered the National League in 1876 as a founding team along with five other former National Association teams and two new professional league entrants.

George Bradley pitched the first no-hitter in Major League history on July 15, 1876, when the Brown Stockings defeated the Hartford Dark Blues, 2–0.

Red Stockings

The St. Louis Red Stockings were a professional baseball team in the National Association of Professional Base Ball Players for the 1875 season. The site where they played their home games is first known to have been used for baseball in about 1867, when it was the home of something called the Veto Club, and was called the Veto Grounds.

The grounds were evidently already well-known, as local newspapers in 1867 were calling it the "old" Veto Grounds. In 1874, the Red Stockings—then a local amateur club—built a grandstand behind home plate and a wooden stockade fence around the field.

Chris von der Ahe

Chris von der Ahe’s meteoric rise to baseball prominence predated the modern-day World Series. Von der Ahe was the owner of the original St. Louis Browns franchise from 1881 to 1899. immigrated alone to New York around 1870 as a teenager with little means. Just six weeks later, von der Ahe traveled west to St. Louis and began a career as a grocery store clerk. Within two years he had saved enough to start his own saloon.

As he heard enthusiastic stories of baseball from his patrons, von der Ahe sensed the game could serve as a business opportunity. As the majority owner of the St. Louis club, von der Ahe transformed the vacant lots next to his saloon into a baseball field that would become known by many names, most notably “Sportsman’s Park.”

American Association

The American Association of Base Ball Clubs was a professional baseball league that existed for 10 seasons from 1882 to 1891. Together with the National League, founded in 1876, the AA participated in an early version of the World Series seven times versus the champion of the NL in an interleague championship playoff tournament. At the end of its run, several AA franchises joined the NL. After 1891, the NL existed alone, with each season's champions being awarded the Temple Cup (1894–1897). Pictured here is the 1885 St. Louis Browns.

St. Louis Maroons

The St. Louis Maroons were a professional baseball team from 1884 to 1886. The club, established by Henry Lucas, were the one near-major league quality entry in the Union Association, a league that lasted only one season, due in large part to the dominance of the Maroons (who started the 1884 season 20-0).

When the UA folded after playing just one season, the Maroons joined the National League. In 1887 the Maroons relocated to Indianapolis and became the Indianapolis Hoosiers, where they played three more seasons before folding.

1892 St. Louis Browns

The 1892 St. Louis Browns season was the team's 11th season in St. Louis, and their first as members of the National League.

The Browns joined the National League when the American Association folded after the 1891 season and have remained a member ever since; the team has been known as the St. Louis Cardinals since 1900. This was the team’s final season before moving from the original Sportsman's Park to New Sportsman's Park.

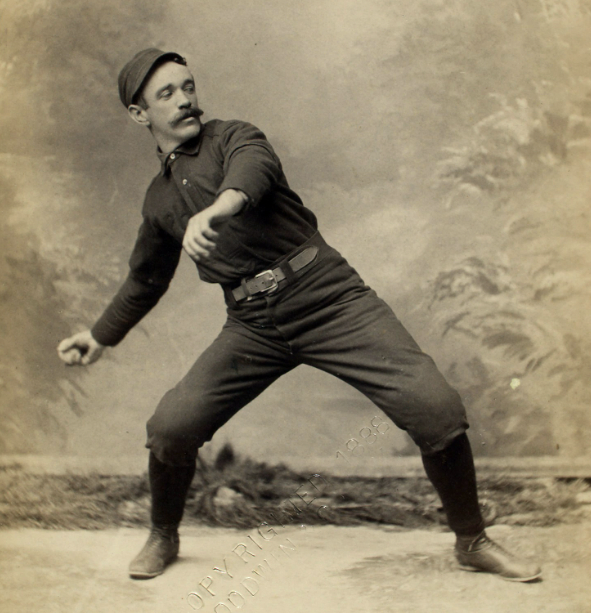

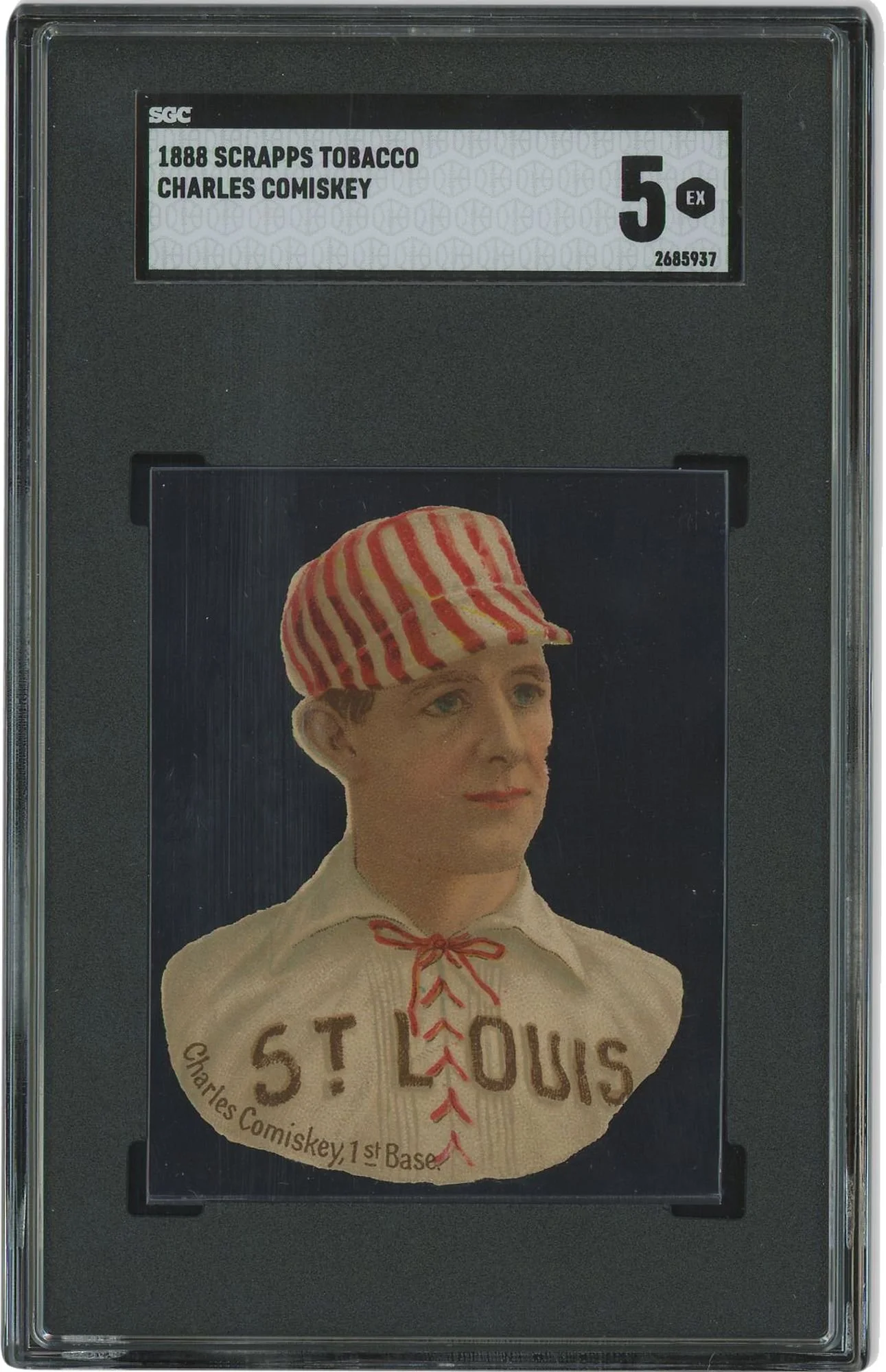

Great Browns Players

Pictured here is the 1896 St. Louis Browns team. Some of the best players of the Browns National League teams of the late 1880s were Bob Caruthers, Tip O’Neill, Arlie Latham, Theodore Breitenstein, and Charles Comiskey.

Bob Caruthers’ SABR Biography

Tip O’Neill’s SABR Biography

Arlie Latham’s SABR Biography

Theodore Breitenstein’s SABR Biography

Charles Comiskey SABR Biography

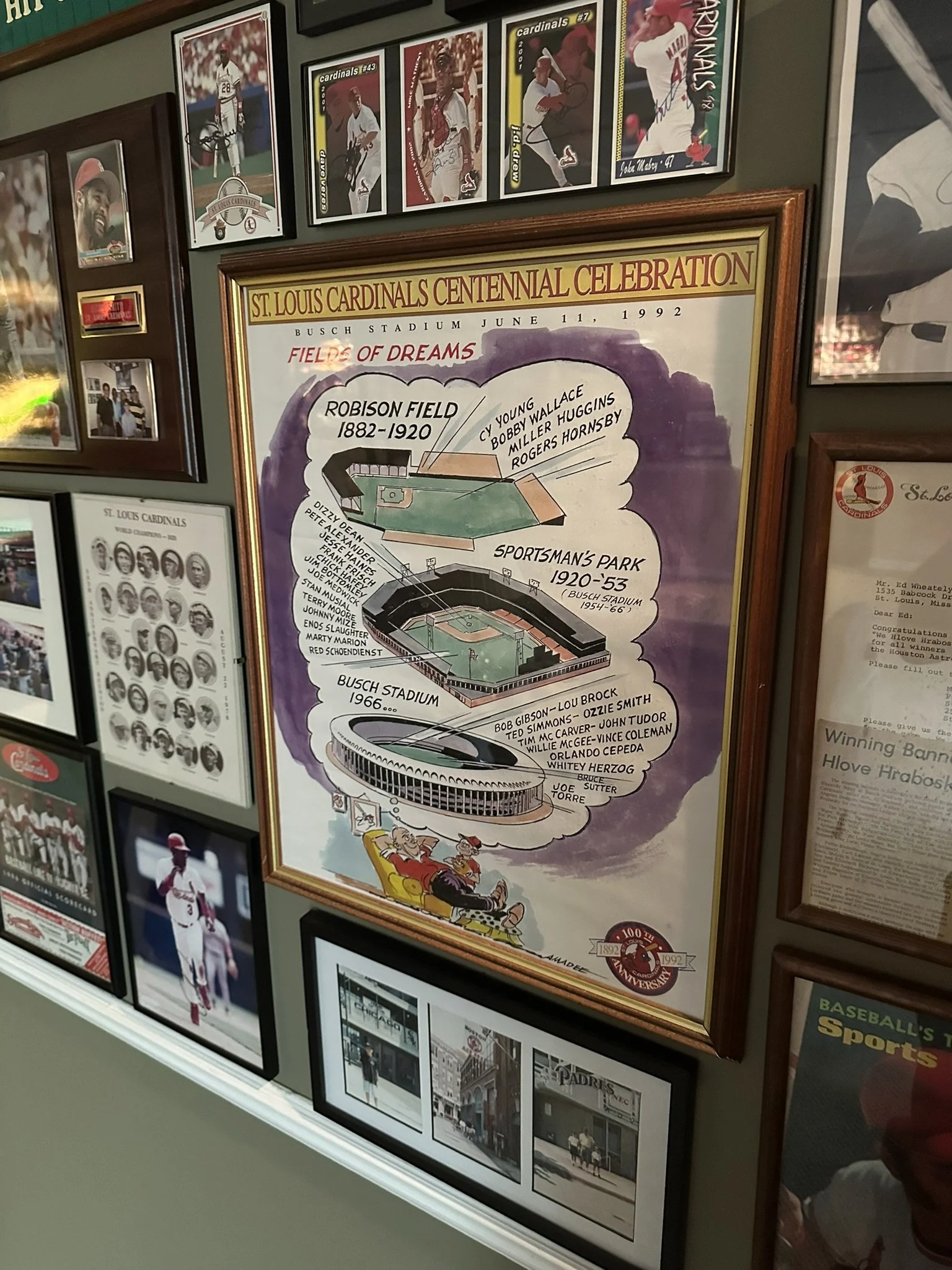

100th Anniversary?

In 1992, the St. Louis Cardinals sold all sorts of memorabilia with this logo on it, from books to baseballs, celebrating the team’s 100th anniversary. But was it really??

Logo courtesy of SportsLogos.net

Charles Comiskey

Charlie Comiskey took over as a full-time player/manager at 25 years of age towards the end of the 1884 season. The unequivocal team leader piloted the Browns to four straight American Association pennants, winning at least two-thirds of his games in each season between 1885 and 1888.

Comiskey’s Browns defeated the National League’s Chicago White Stockings (led by Hall of Fame player/manager Cap Anson) four games to two in the 1886 World’s Championship Series, staged between the two leagues in a prelude to the modern-day World Series.

Heralded as a solid defender, “The Old Roman” is widely credited as being one of the first players not to hug the first base bag, but rather played closer to second base, enabling him to field more ground balls and having the pitcher cover first base.

Comiskey was an organizational selection to be inducted into the Cardinals Hall of Fame Class of 2022.

Concentrated Greatness

Not only did St. Louis have an American League and a National League team (who played in the same park for many years, no less), they also had a Federal League team and multiple Black baseball teams over the years, as well.

Looking at this map of the area shows you exactly how close together all of their stadiums were, and how easy it was for fans to know where to go to see great baseball being played.

The Robison Brothers

The team had new owners as the Robison Brothers, Frank and Stanley, bought the team from the outrageous but business minded Chris Von der Ahe. Frank was in business with his father-in-law, Charles Hathaway, operating cable cars in Cleveland and Stanley had a degree in civil engineering and moved to Fort Wayne, Indiana where he also worked with his brother at the Hathaway and Robison, Street Railway Contractors and Builders based out of Cleveland. Stanley would oversee the business holdings from his home in Fort Wayne.

The Robison brothers changed the team color to red, and the name of the ballpark to League Park (the same name of the park they owned in Cleveland). The red color proved so popular that fans and sportswriters began referring to the team by the shade of red: cardinal. The next season, the team officially became the Cardinals.

1899 St. Louis Perfectos

The 1899 team benefited from many players who were transferred from the Cleveland Spiders, who were also owned by the Robison brothers. This led to the Spiders compiling the worst season in MLB history, losing 134 games. However, the Perfectos wound up finishing only fifth.

The pennant-winning Brooklyn Superbas benefited from a similar arrangement. Brooklyn's owners also owned the Baltimore Orioles, allowing them to also transfer their better players to one team. After the 1899 season, such arrangements were outlawed in the National League. Both the Spiders and Orioles were among four teams eliminated from the league.

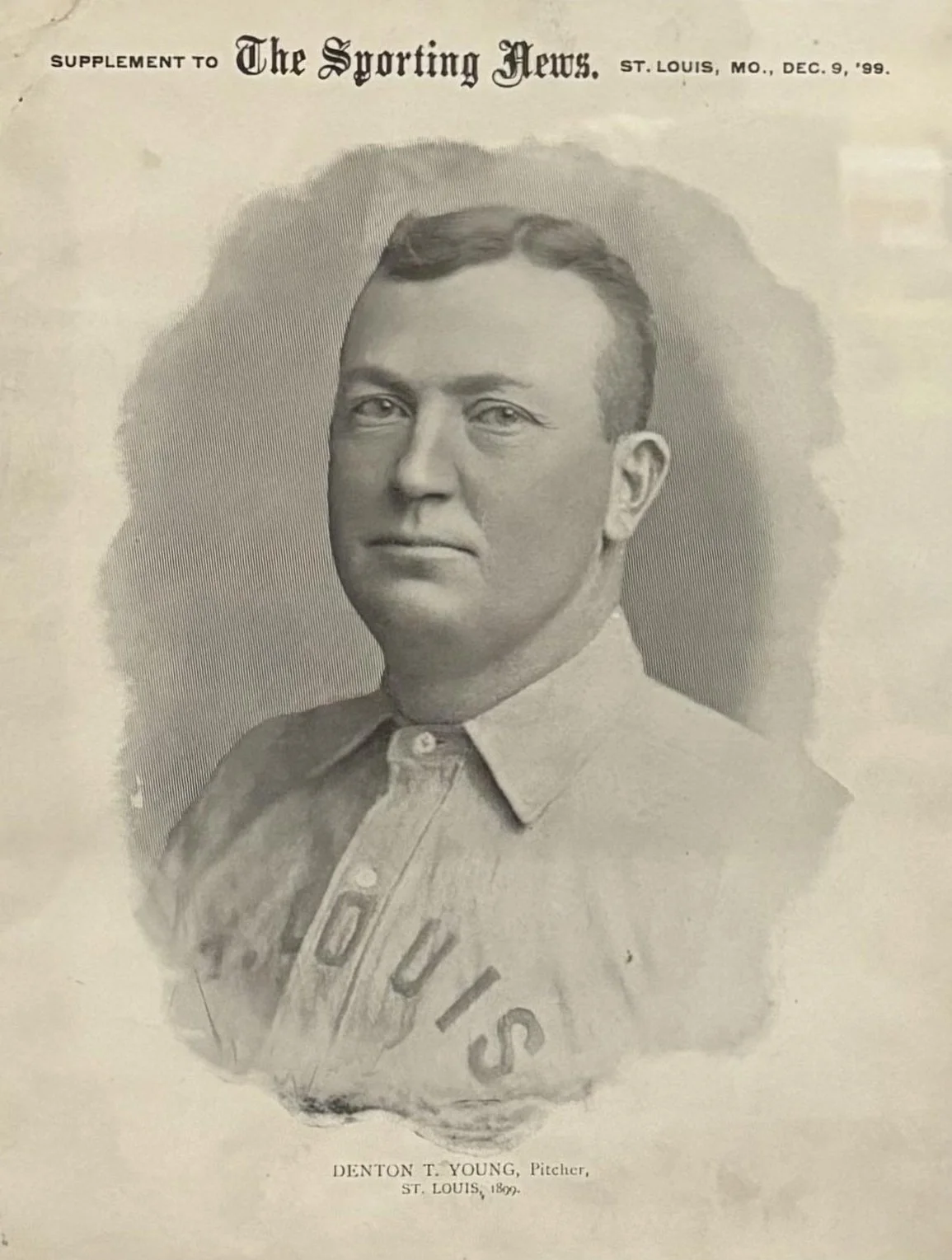

Cy Young

Cy Young holds nearly all of the career counting statistics records for pitchers, including most Wins all time (511), most Losses (315), most Games Started (815), most Complete Games (with 749!), most Innings Pitched, most Batters Faced, and a handful of others.

He passed away in 1955, and in 1956, they started calling the award given to the best pitcher at the end of every season the Cy Young Award.

Jesse Burkett

Jesse Burkett was transferred to the St. Louis Cardinals in 1899 by the Spiders’ owner Frank Robison, who owned both teams. That year, Burkett hit .396 – a figure that was revised down from .402 in future years. After two more seasons with the Cardinals – which included a .376 average in 1901 that was good for his third National League batting crown – Burkett jumped to the St. Louis Browns of the American League for three years.

Burkett actually batted over .400 twice and held the major league single-season hits record for 15 years. In 1946, Burkett was elected into the National Baseball Hall of Fame. Burkett holds the record for the most inside-the-park home runs in MLB history, with 55.

For his career, Burkett compiled a .338 batting average on the strength of 2,850 hits. He scored 1,720 runs and notched 320 doubles.

1901 Milwaukee Brewers

The American League started in 1901 and had a team in Milwaukee (called the Brewers), who finished in dead last place with a record of 48-89.

For some reason, though, St. Louis did not have an American League franchise, despite being the 4th largest city in America at the time.

Ban Johnson, the President of the American League, saw that as a missed opportunity, and had the Milwaukee Brewers move to St. Louis for the 1902 season, renaming them the St. Louis Browns.

Bobby Wallace

“[Bobby Wallace] is one of the greatest fielding shortstops who ever lived,” fellow St. Louis Browns player Jimmy Austin said. “It was a delight to play third base next to that fellow.”

In 1901 with the St. Louis Cardinals, Wallace led all National League shortstops in chances per game, assists and double plays and was still a threat at the plate, batting .324 with 91 RBI.

He jumped to the American League's St. Louis Browns in 1902, holding down the starting shortstop job for 11 seasons. He also served as the team's manager during the 1911 and 1912 seasons. He was elected to the Hall of Fame in 1953.

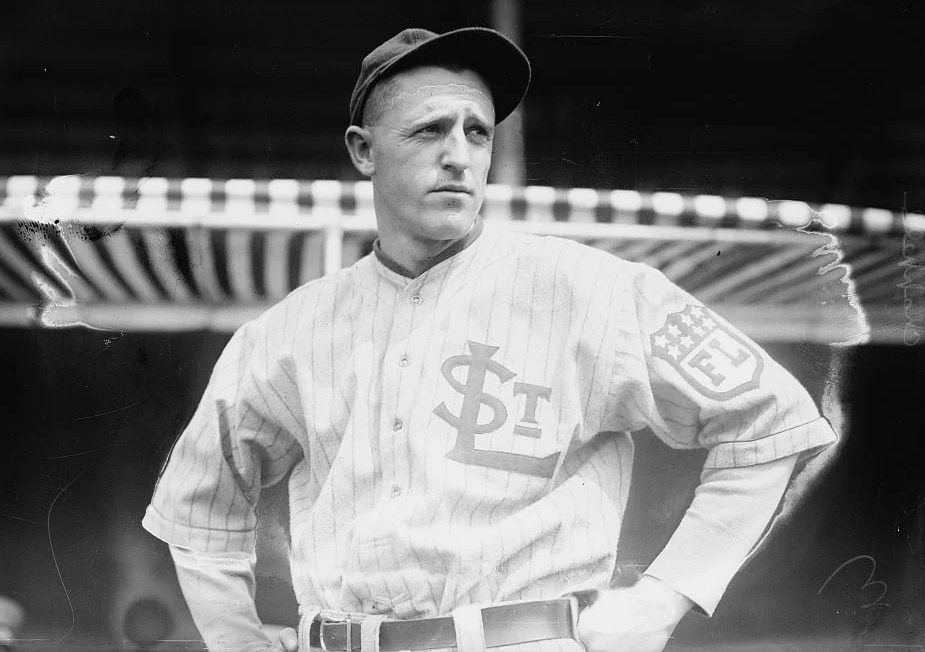

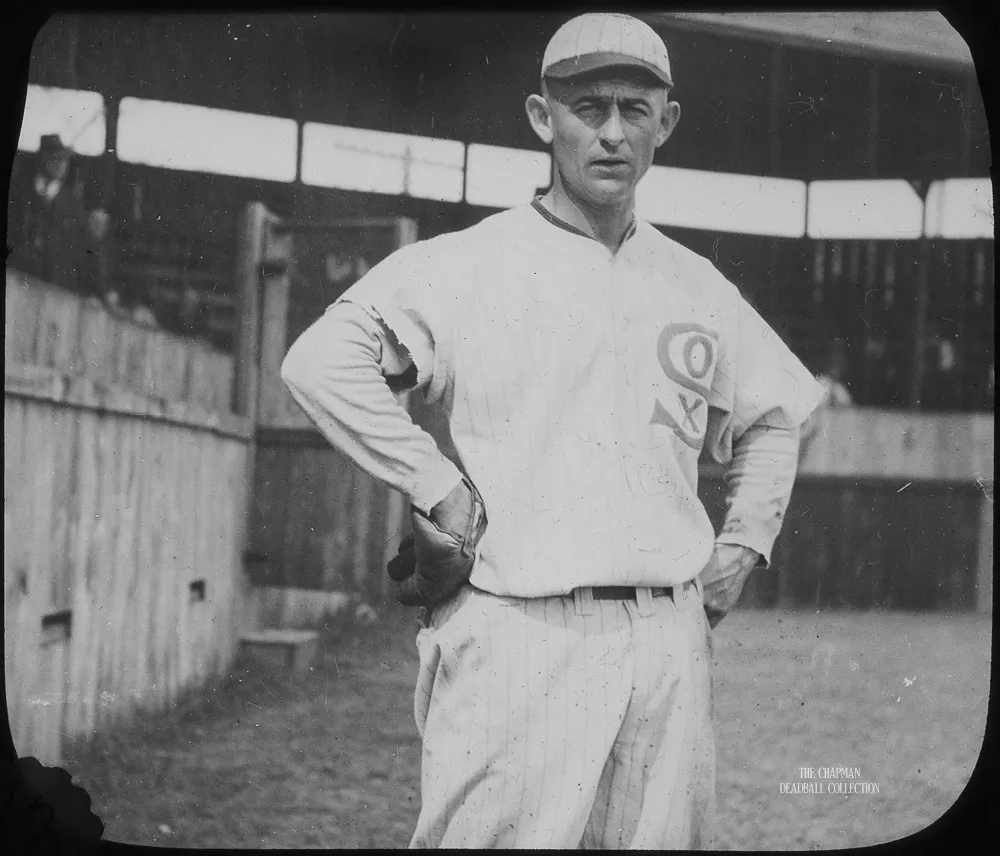

Branch Rickey

Branch Rickey had a brief and undistinguished career as a major league catcher for the St. Louis Browns (1905–1906) and New York Highlanders in 1907. On offense, his batting average dropped below .200; on defense, an opposing team once stole 13 bases in a single game, thanks to Rickey’s weak throwing arm.

Photo courtesy of National Photo Company Collection, Prints and Photographs Division, Library of Congress, LC-DIG-npcc-19279

Branch Manager

Rickey enrolled at the University of Michigan’s Law School. In his second year, he signed on to coach the university’s baseball club, where he mentored George Sisler. Between 1910 and 1913, Rickey earned a 68-32-4 record. Despite his limited success as a player, the St. Louis Browns rehired Rickey to serve as the team’s manager from 1913 to 1915.

The St. Louis Browns outfield of Ken Williams in left, Baby Doll Jacobson in center, and Johnny “Jack” Tobin in right, was a talented trio on an under-performing team.

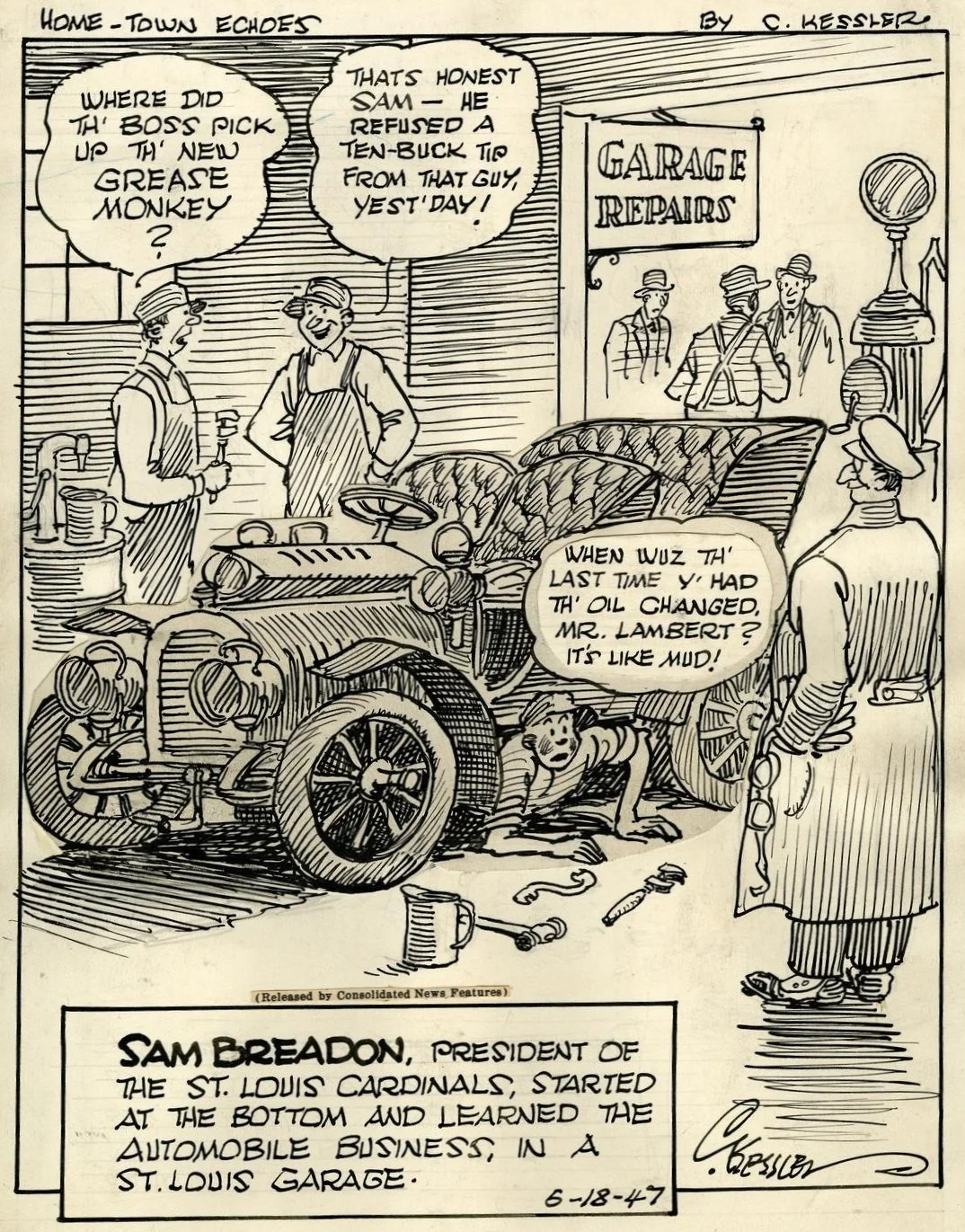

Sam Breadon

Sam Breadon bought a minority interest in the Cardinals in 1917, and two years later, in 1919, Browns manager Branch Rickey joined the Cardinals. Breadon bought out the majority stake in 1920 and appointed Rickey as the team’s business manager.

The Cardinals won nine pennants and six World Series from the time Breadon took over in 1920 until he sold the club in November of 1947. The Cardinals’ record during that time was 2,470-1,830 (.574).

“I realized that it’s the ballclub that counts, not the individual,” Breadon said. “And I never again was afraid to trade a player.”

Helene Hathaway Britton

In March 1911, with woman suffrage a popular topic in the newspapers, a major league baseball club owner’s death caused a stir in the worlds of sports and society. The will left by Stanley Robison revealed that he had bequeathed controlling interest in the St. Louis Cardinals to his niece, Helene Robison Britton. The remaining shares went to Helene’s mother, the widow of former club co-owner Frank DeHaas Robison, Stanley’s brother.

Early reports dismissed the notion that a woman - or women - would maintain ownership, least of all control, of a baseball franchise. But Helene, a young wife and mother of two small children, surprised the male-dominated world of baseball by not only refusing to sell her acquisition but taking an active role in its operation for the next six years, becoming the first woman in history to own a major league baseball club.

National League owners at the December 1911 league meeting. Helene Hathaway Britton is the only woman present.

The Minor League Farm System

Branch Rickey conceived the minor league farm system in an attempt to bolster his club, a concept he tried to pursue while with the Browns.

By leasing use of Sportsman’s Park from the Browns instead of building their own stadium, the Cardinals were able to afford to implement Rickey’s idea for a farm system. That’s when the franchise took off.

Sam Breadon

On June 6, 1920, the Cardinals played their last game at Robison Field (renamed Cardinal Field in 1917), which had been their home field since 1893. They beat the Cubs, 5-2.

One of Sam Breadon’s first decisions as the team’s new owner was to agree to a ten-year lease for $20,000 annually, allowing his team to move six blocks to share Sportsman’s Park with the Browns, and allowing him to use the money from the sale of the aging ballpark to finance Branch Rickey’s idea of establishing a farm system by investing in a club affiliation with a minor league team in Houston, Texas.

This cartoon depicts Sam Breadon as a mechanic in a St. Louis garage. Long before becoming the President of the Cardinals, Breadon moved to St. Louis as a struggling, young mechanic from New York.

Photo courtesy of the National Baseball Hall of Fame Library

Robison Field

Robison Field is the best-known of several names given to a former Major League park in St. Louis. It was the home of the Cardinals from April 27, 1893 until June 6, 1920.

Robison Field was the last remaining major league ballpark that was primarily wooden. The Cardinals sold the property to the developers of Beaumont High School, which was built on the site and was opened in 1926.

This photo depicts a fire at the field on May 4, 1901.

The new Sportsman’s Park was state of the art when it was built in 1909. Since it was constructed with steel and concrete, it was not susceptible to fires in the same way that previous wooden ballparks had been.

Philip De Catesby Ball

Philip De Catesby Ball is perhaps best known for demoting pioneering baseball executive Branch Rickey from general manager to business manager in 1915, which led to his departure for the Cardinals.

He considered Rickey's ideas, such as the development of an integrated farm system, to be too radical for the time; however, he also sought to prevent other teams from experimenting with these ideas by unsuccessfully seeking a court order to vacate Rickey's 1917 contract with the Browns' crosstown rivals.

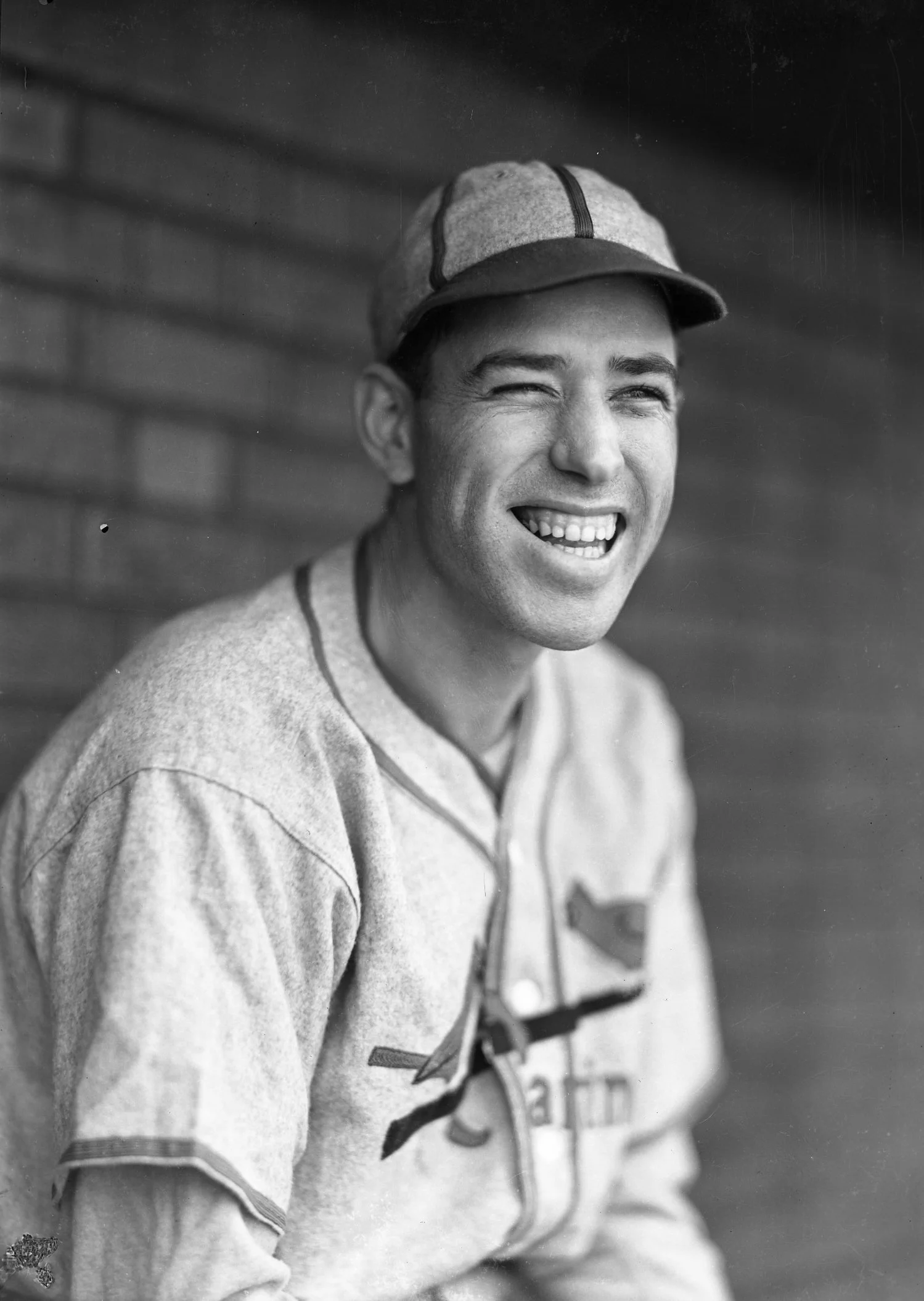

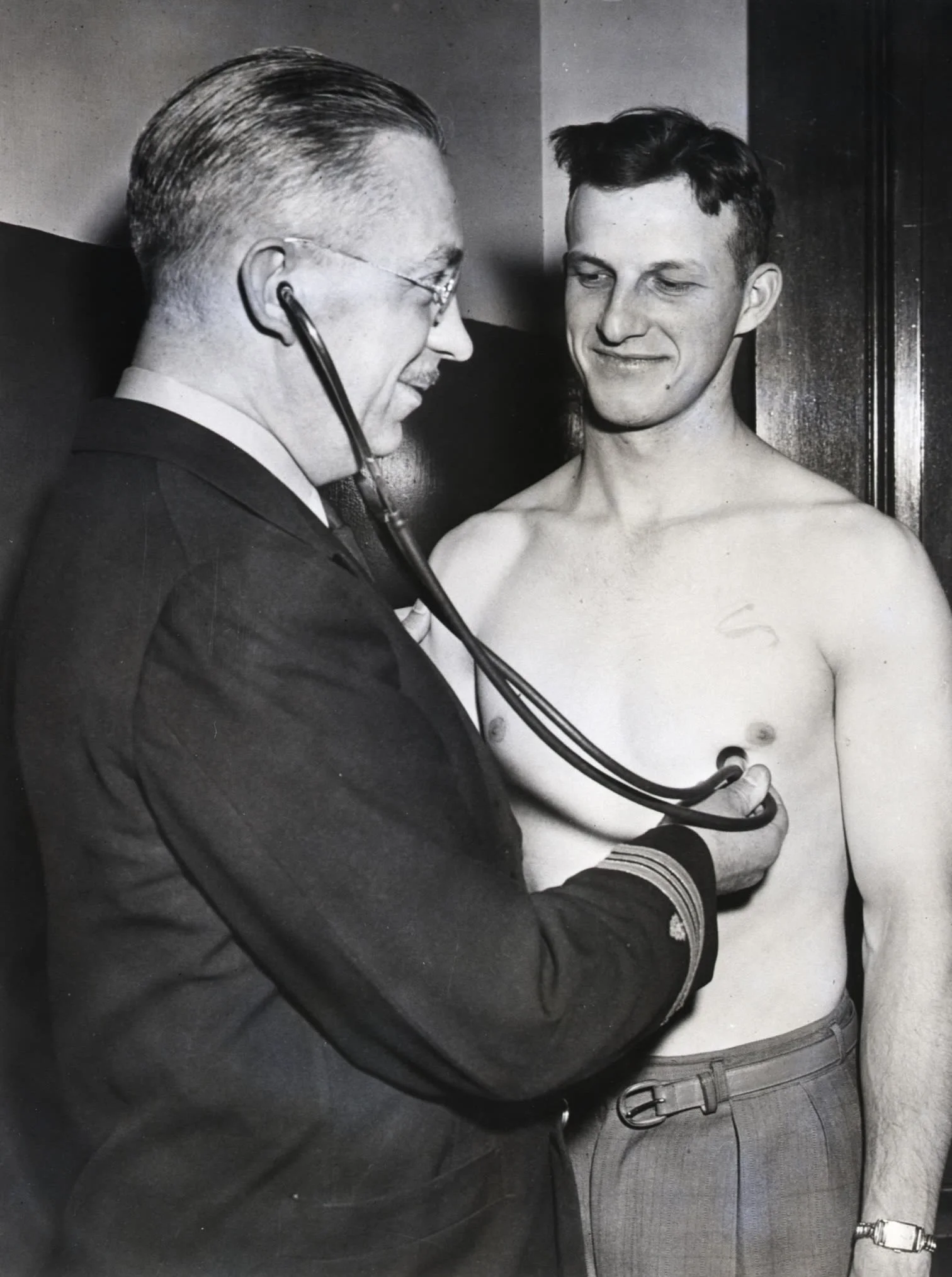

Birds on Bat

In 1922, the Cardinals introduced the Birds on Bat logo and wore it on their uniform for the first time. Here, Austin McHenry proudly shows off the new threads.

By the time he was 25 years old, St. Louis Cardinals outfielder Austin McHenry was considered one of baseball’s best outfielders and hitters, especially after enjoying a 1921 season that saw him finish with a .350 batting average, second only to teammate and future Hall of Famer Rogers Hornsby.

McHenry also finished second to Hornsby in slugging at .531, placed among the top five National League hitters in doubles, home runs, RBIs, total bases, and extra-base hits, and was one of only six N.L. hitters with 200 hits that season.

Combined with a strong arm and an easy gait that was sometimes mistaken for indifference, McHenry was considered not only one of baseball’s best outfielders and hitters after his remarkable 1921 campaign, but one of the ten best left fielders of all time to that point in baseball history.

Austin McHenry’s SABR Biography

Photo courtesy of cardinalsuniformsandlogos.com

Peter Capolino

Peter Capolino is the founder and former owner of the Mitchell & Ness Nostalgia Co. in Philadelphia. Peter is nearly single-handedly responsible for the proliferation of throwback jerseys and the uniform literacy of the average fan.

He was our guest for Episode 3 of Season 3. You can listen to that episode HERE.

Allie May Schmidt

The Birds on the Bat design originated from hand-painted cardboard birds created by Allie May Schmidt. She was asked to create table decorations for a Men’s Fellowship Club event at the Ferguson Presbyterian Church on February 16, 1921.

Allie May was inspired when she saw cardinal birds perched on a lilac bush. Branch Rickey was in attendance at the event, and was impressed with Allie May’s painted cardboard birds (seen here).

Rickey commissioned Allie May’s father, Edward H. Schmidt, who was head of the art department at the Woodward and Tiernan Printing Company, to create a new design for the team’s uniforms. The uniforms debuted in an exhibition game against the American League St. Louis Browns on April 8, 1922.

Photo courtesy of cardinalsuniformsandlogos.com

Single Bird

Newspaper accounts for the 1923 season claim the Cardinals wore the Single Bird as their primary weekday uniform, and the Birds on the Bat as their Sunday uniform. However, collaborative research efforts between cardinalsuniformsandlogos.com and Jeff Scott at birdbats.com has lead us to refute the newspaper claim. According to our photo identification and Jeff Scott’s player number identification, we think the Cardinals wore the Birds on the Bat at home on weekdays and wore the Single Bird uniform on Sundays.

Variations of the Single Bird uniform were also used during the 1927 season, with the words WORLD CHAMPIONS surrounding the bird on the left chest.

The Cardinals’ 1928 home uniform, which was also worn for Game 3 of the 1928 World Series, was also a variation of the Single Bird logo.

Here, Fred Toney models the 1923 version.

Photo courtesy of cardinalsuniformsandlogos.com

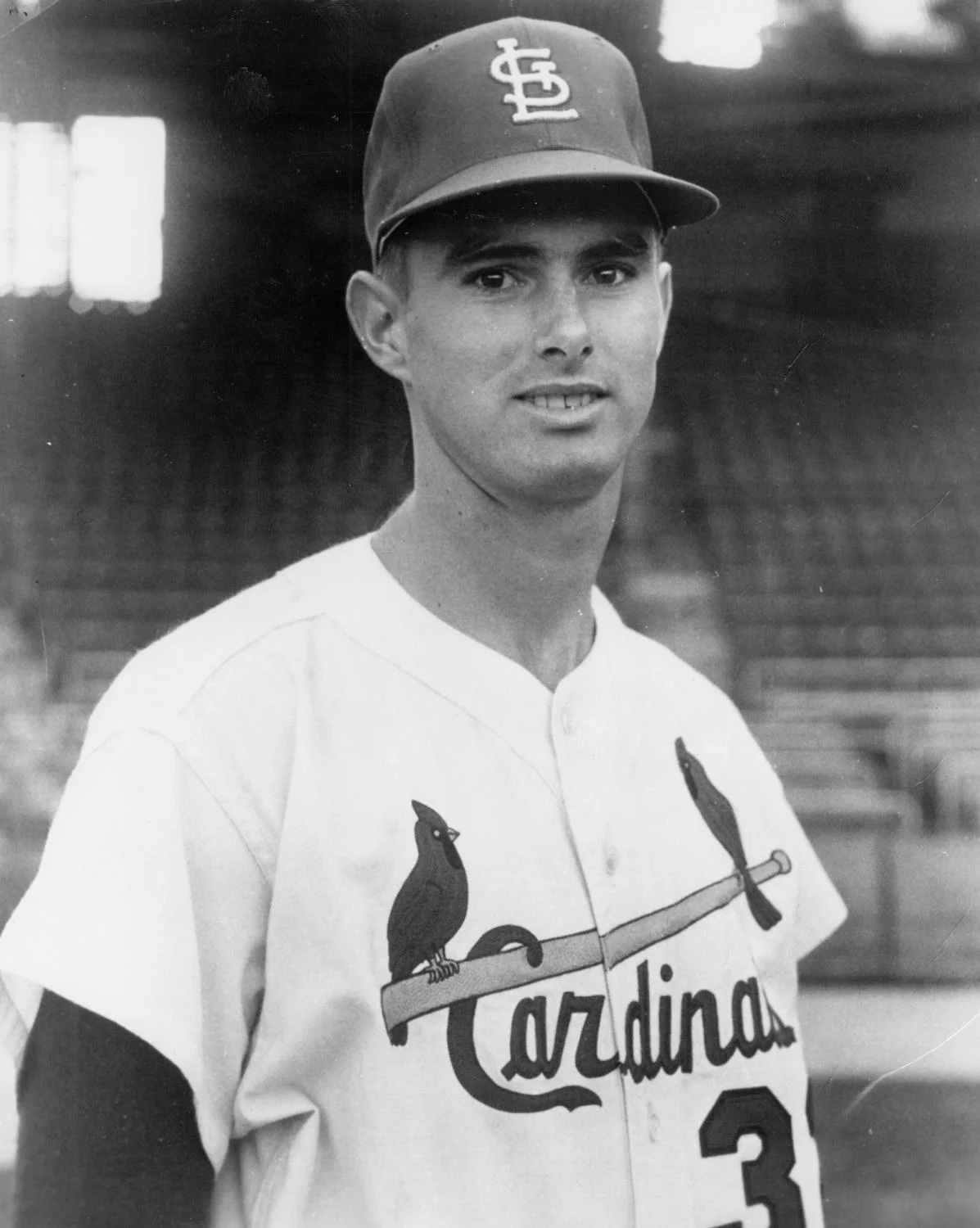

1956 Cardinals Uniforms

The 1956 Cardinals uniforms may be the most controversial of all time. General Manager Frank Lane, the man who traded Red Schoendienst in 1956, and who also attempted to trade Stan Musial, removed the Birds on the Bat from the uniforms. In its place was a cursive script that read Cardinals.

Sluggerbird was embroidered on the left sleeve, batting left handed. This is the first season Sluggerbird appeared on the team’s jersey.

Frank Lane’s original plan was to only wear the cursive script at home, and wear an interlocking STL on the chest for the the road uniform.

Photo courtesy of cardinalsuniformsandlogos.com

Slight Changes

In 1951, the team refreshed their look with a new Birds on the Bat logo across the chest. It was the first Birds on the Bat logo to feature a yellow/gold bat, as opposed to the black bats which had always adorned the logo since their inception on the 1922 uniforms. The bat has remained yellow/gold since 1951.

The Cardinals also wore a sleeve patch during the 1951 season, commemorating 75 years of the National League.

Here, Red Schoendienst is seen wearing the 1951 Cardinals uniform.

Red Schoendienst’s SABR Biography

Photo courtesy of cardinalsuniformsandlogos.com

St. Louis Browns Logo

The Apotheosis of St. Louis is a statue of King Louis IX of France (who is the namesake of St. Louis, Missouri) which is located in front of the Saint Louis Art Museum.

Part of the iconography of St. Louis, the statue was the principal symbol of the city between its erection in 1906 and the construction of the Gateway Arch in the mid-1960s.

The eight stars represent the eight original teams of the American League, while the nine bars represent the nine innings of a baseball game, and the nine players on each team.

Logo courtesy of SportsLogos.net

Ed At The Hall Of Fame

Ed has spoken at the National Baseball Hall of Fame in Cooperstown a number of times. Here he is on one of his visits to the Hall with Mary Moore, Maybelle Blair, and Shirley Burkovich of the All-American Girls Professional Baseball League.

Rogers Hornsby

The best player on the team during this era was second baseman Rogers Hornsby, who was a Cardinal from 1915-1926, and then again for 46 games in 1933. He is, perhaps, the greatest right handed hitter in baseball history.

He led the National League in batting seven times, including an incredible six-year stretch from 1920 through 1925 during which he averaged .397. He won the Triple Crowns in 1922 and 1925, and the Cardinals won the 1926 National League pennant and World Series, the first time they had won either.

Hornsby was the player/manager of the Cardinals in 1925 and 1926, yet two months after winning the championship, he was fired.

Babe Promises A Homer

Resting in bed in Essex Fells, 11-year-old Johnny Sylvester told his dad the only thing that could cheer him up would be a baseball from the World Series between the Yankees and Cardinals. His father asked a well-connected friend for help. Days later, both the Cardinals and Yankees shipped signed balls to Johnny’s dad – with Ruth scrawling, “I’ll knock a homer for you in Wednesday’s game.”

Sure enough, Ruth hit not one but three home runs in Game 4. Alas, the Bombers lost the series in seven games.

Soon after, on Oct. 11, 1926, Ruth and his business manager, Christy Walsh, visited Johnny at home in Essex Fells. The next day, the Daily News ran a front-page photo of Ruth and Johnny shaking hands, with the headline “‘Dr.’ Babe Ruth at Bedside.”

Right Field at Sportsman’s Park

During the 1929 season, the visiting Detroit Tigers hit eight home runs in a four-game series (July 2-4). Surprisingly, the Browns won three of the four games. Nonetheless, in an effort to help the Browns shell shocked pitching staff, Browns management used the off-day of July 5 to install a 21 1/2-foot screen in RF, placed above the existing wall.

The screen was in play and raised the barrier to RF homers from 11.5 to 33 feet. The screen ran from the foul line to about right center-near the 354-ft. mark, and covered nearly all of right field.

Grover Cleveland Alexander

In Game 6 of the 1926 World Series, 39-year-old Grover Cleveland Alexander tossed a complete game eight-hitter, holding the Yankees to just two runs in St. Louis’ 10-2 win, tying the Series at three games apiece.

Without a single day of rest, Cardinals manager Rogers Hornsby summoned Alexander from the bullpen in Game 7 with the bases loaded, two outs and future Hall of Famer Tony Lazzeri at the plate – and St. Louis clinging to a 3-2 lead in the 7th inning.

Lazzeri missed a grand slam by the slimmest of margins with a blast down the left-field line, then struck out to end the inning. Alexander’s heroics gave the Cardinals their first World Series title.

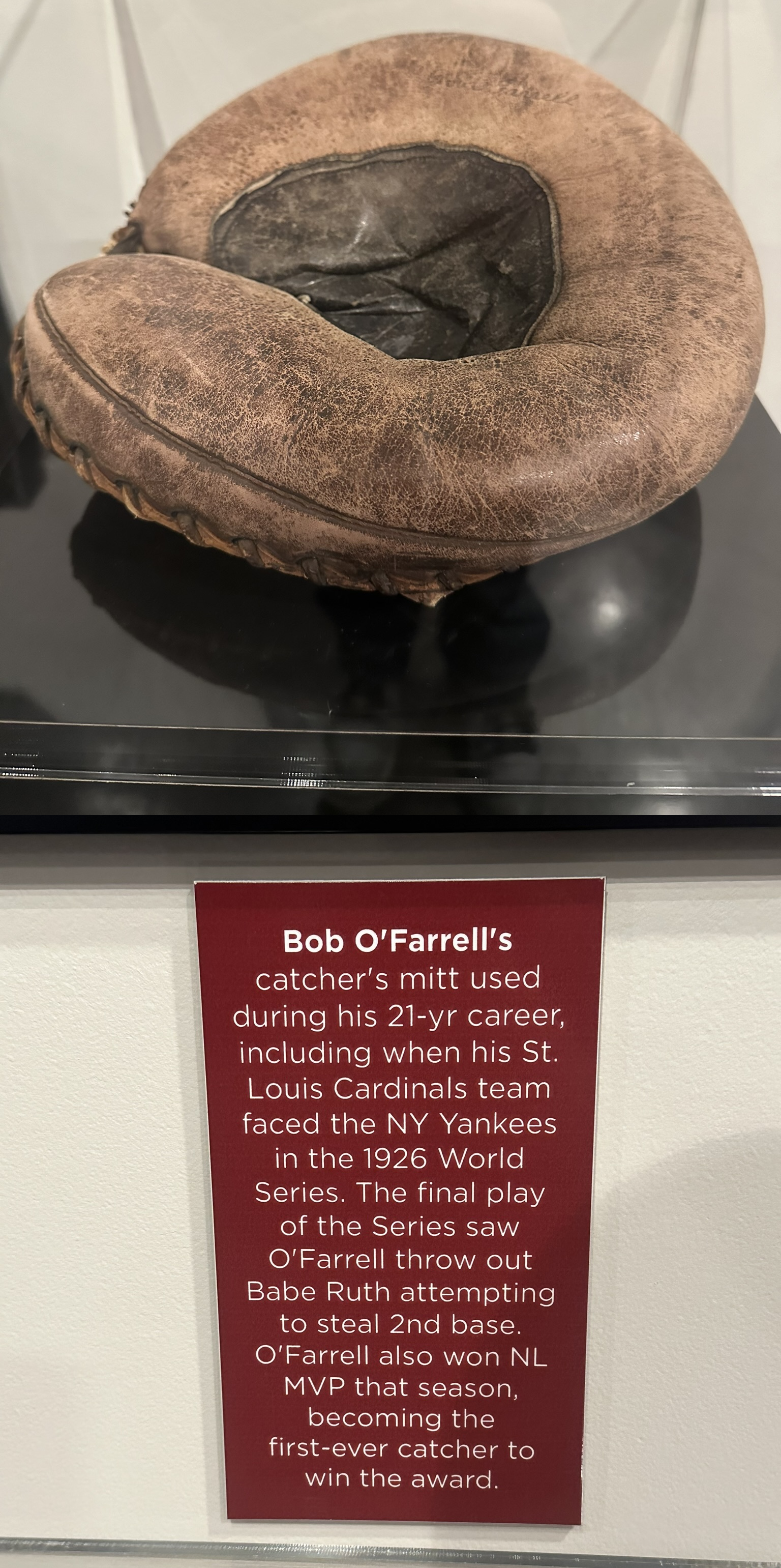

Bob O'Farrell

Bob O'Farrell played 21 seasons in Major League Baseball with the Chicago Cubs, St. Louis Cardinals, New York Giants, and Cincinnati Reds. He was considered one of the greatest defensive catchers of his generation.

O'Farrell experienced the highlight of his career in 1926 when he hit for a .293 average with a career-high 30 doubles, 7 home runs and 68 runs batted in as he helped the Cardinals clinch the National League pennant. He also led National League catchers in games caught and in putouts.

In the 1926 World Series against the New York Yankees, O'Farrell produced a .301 batting average, but is remembered for throwing out Babe Ruth trying to steal second base for the last out of the seven-game series as the Cardinals claimed their first-ever world championship.

In November of 1926, he was voted the winner of the 1926 National League Most Valuable Player Award with 79 out of the possible 80 votes. He was the first catcher to win a Most Valuable Player Award.

In December of 1926, the Cardinals traded their manager, Rogers Hornsby, to the New York Giants for Frankie Frisch and Jimmy Ring, and subsequently named O'Farrell player-manager.

This glove is on display at the Grovewood Baseball Museum in Tennessee.

Breadon vs. Hornsby

Left to right, at the 1926 World Series: Sam Breadon, Mrs. William Niekamp, Mrs. Breadon, Mrs. Hornsby, Rogers Hornsby

After the 1926 season, Rogers Hornsby and Cardinals owner Sam Breadon quarreled during contract talks. Reaching a boiling point, Hornsby stormed out of Breadon’s office, slamming the door behind him, triggering his banishment from the club.

Photo courtesy of the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum

Rogers Hornsby with William Veeck, Sr. (left) and Bill Veeck (right). Neither relationship ended amicably, prompting Bill’s mom to ask her son, “Did you not learn anything from your father?!”

Hank “Bow Wow” Arft

Hank Arft played first base for the St. Louis Browns from 1948 to 1952. His top season was 1951, during which he achieved career highs in wins above replacement, games played, plate appearances, hits, home runs, RBIs, stolen bases, total bases, and OPS+.

Arft suffered a concussion during batting practice on May 24, 1952, when manager Rogers Hornsby refused to let the infielders take their reps with the protection of a screen as the batters hit balls into play. X-rays showed no fracture, but Arft missed the next two weeks, and the team grew more resentful of Hornsby’s decision making.

Hornsby in the Hall

Rogers Hornsby was inducted into the National Baseball Hall of Fame in 1942, and rightfully so; he’s one of the greatest players to ever live.

Since 1900, only two players have batted .400 on three occasions – Ty Cobb and Rogers Hornsby.

Only two players have won multiple Triple Crowns – Ted Williams and Hornsby.

Retired “Number”

Although he wore a couple different uniform numbers with the Cardinals when uniform numbers were first becoming a thing, there isn’t a single number that is truly connected to him.

The Cardinals honored him by “retiring” his uniform with an “SL” emblem instead of a number, so he is recognized in the ballpark as one of the franchise’s truly great players.

Joe “Ducky” Medwick

In just his second full season in the big leagues in 1934, Joe Medwick had already established himself as one of the National League’s best hitters at age 22 and led the Cardinals to the World Series. Medwick opened Game 1 with four straight hits (including a home run) and went on to hit .379 in seven games against the Tigers, winning his first and only World Series ring.

A solid defensive outfielder, Medwick would go on to become one of the National League’s most dangerous hitters in the 1930s. After Top 5 finishes in the NL MVP race in 1935 and 1936, Medwick received the NL MVP in 1937 when he won the NL Triple Crown and also led the league in hits, runs, doubles, total bases and slugging percentage.

The Cardinals unveiled the new display for their retired numbers on their outfield wall before the 2022 season.

1931 Cardinals

The 1931 Cardinals went 101-53, and won their second World Series. The team featured Chick Hafey and Pepper Martin in the outfield, Jim Bottomley at first base, and Frankie Frisch at second.

The pitching staff included Bill Hallahan, Burleigh Grimes, and Jesse Haines.

Chick Hafey’s SABR Biography

Pepper Martin’s SABR Biography

Jim Bottomley’s SABR Biography

Frankie Frisch’s SABR Biography

Bill Hallahan’s SABR Biography

Burleigh Grimes’ SABR Biography

Jesse Haines’ SABR Biography

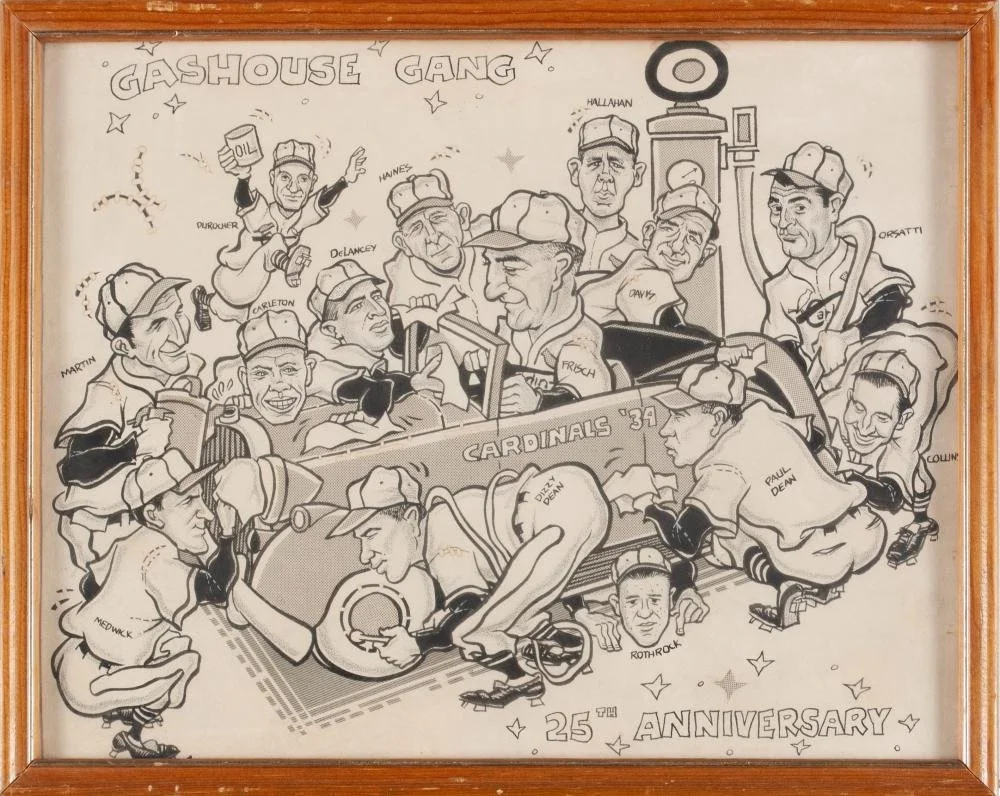

"The Gashouse Gang”

The nickname Gashouse Gang, by most accounts, came from the team's generally very shabby appearance and rough-and-tumble tactics. An opponent once stated the Cardinals players usually went into the field in unwashed, dirty, and smelly uniforms, which alone spread horror among their rivals.

According to one account, shortstop Leo Durocher coined the term. He and his teammates were speaking derisively of the American League, and the consensus was that the Redbirds — should they prevail in the NL race — would handle whoever won the AL pennant. "Why, they wouldn't even let us in that league over there. They think we're just a bunch of gashousers."

The Team… Band?

Outfielder Pepper Martin got some of his teammates together and started a band called the Marvelous Musical Mississippi Mudcats. It included pitcher Bill McGee, Frenchy Bordagaray, Ripper Collins and Bob Weiland.

in 1936, Collins was traded to the Cubs and Martin's Mudcats lost a musician. Happily, during a Cubs-Cardinals game on September 10, 1937, they got the band back together. In the photo seen here, you can spot Collins thanks to his Cubs jersey.

Left to right, the rest of the group is: Bordagaray, McGee, and Martin resting his leg on a bat. Pitcher Bob Weiland is playing glove in the back.

CLICK HERE to listen to James McDonald’s SABR 51 presentation about the band.

Jim Bottomley

In his 11-year tenure with the Cardinals organization, he made an indelible mark on the team, city and their fans – with one of his most memorable moments coming in 1928, when he was named the National League’s Most Valuable Player.

In 1928, Bottomley batted .325 and posted league-leading numbers in home runs (31), RBIs (136) and triples (20). His efforts propelled the Cardinals to the National League pennant.

From 1926-31, “Sunny Jim,” as he was often referred to for his light-hearted disposition, led the Cardinals to the World Series four times (1926, 1928, 1930-31) with his stellar regular season stats. From 1924-29, he posted 100 or more regular season RBI and batted .300 or better from 1927-31.

Pepper Martin

Going into the 1931 season, Pepper Martin’s major league career amounted to playing in just 45 games with the Cardinals in 1928 and 1930. He remained primarily a bench player until June 15, when the Cardinals traded outfielder Taylor Douthit to the Cincinnati Reds. The trade finally allowed him to crack into the everyday lineup.

Martin finished the regular season with a .300 batting average and 16 stolen bases in 123 games, leading all of the team’s outfielders with 282 putouts.

Paul “Daffy” Dean

“We’re just a couple of natural born pitchers from down Texas way,” bantered Paul “Daffy” Dean about himself and his famous brother, Dizzy. “Two good natured ordinary fellers who God gave perfect pitchin’ bodies.”

After Dizzy worked on a no-hitter for 7⅓ innings in the first game of a doubleheader on September 21, 1934, Daffy upstaged his loquacious older sibling by tossing a no-hitter to complete the St. Louis Cardinals’ shutout sweep of the Brooklyn Dodgers.

“There’s little you can add when writing about the Deans,” quipped Brooklyn sportswriter Tommy Holmes. “Superlatives are useless.”

Jay Hanna “Dizzy” Dean

Dizzy Dean made his professional debut in 1930 and worked his way up to the major leagues that same year, throwing a complete game three-hitter for a win with the Cardinals on the final day of the season.

Dean became a regular starter for St. Louis in 1932, leading the league in shutouts and innings pitched. It was also the first of four straight seasons he led the league in strikeouts. The four-time All-Star won 150 games in 12 seasons, with 1,163 strikeouts and a 3.02 career ERA.

"When ole Diz was out there pitching it was more than just another ballgame,” said teammate Pepper Martin. “It was a regular three-ring circus and everybody was wide awake and enjoying being alive.”

Jesse “Pop” Haines

Jesse Haines played his first full season in the major leagues as a 26-year-old in 1920. Despite the late start, Haines would pitch for the next 18 years for the Cardinals thanks to his knuckleball. He finished his career with 210 wins and a 3.64 ERA.

Haines pitched in four World Series, helping the Cardinals to two championships. The first of those titles came in 1926. He beat the Yankees twice in the Fall Classic, shutting them out in Game 3 and winning Game 7 with help from Grover Cleveland Alexander's legendary relief appearance. Haines built on the momentum from the World Series to have the best season of his career in 1927. That year he went 24-10 with a 2.72 ERA and led the National League in complete games (25) and shutouts (six).

In the first game of a doubleheader against the Brooklyn Dodgers on September 21, 1934, Dizzy Dean (right) threw a three-hitter. In the second game, his brother, Daffy (left), threw a no-hitter.

X-Rays of Dean’s Head Show Nothing

Sent to first base as a pinch-runner in Game 4 of the 1934 World Series, Dizzy Dean attempted to break up a double play on a ground ball. The second baseman's throw ended up hitting him square in the head, knocking him unconscious.

Dean's X-ray at the hospital came back negative -- giving way to a supposed newspaper headline of "X-rays of Dean's head show nothing."

That nothing came back to pitch in Game 5 and toss a World Series-winning, complete game shutout in Game 7.

Clockwise from top left: Frenchy Bordagaray, Lon Warneke, Pepper Martin, Bob Weiland

Frankie Frisch

After Frankie Frisch was done managing, he became a member of the Hall of Fame's Committee on Baseball Veterans, which is responsible for electing players to the Hall of Fame who had not been elected during their initial period of eligibility by the Baseball Writers; Frisch eventually became chairman of the committee.

In the years just prior to his death, a number of his Giants and Cardinals teammates were elected to the Hall of Fame, including Jesse Haines, Dave Bancroft, Chick Hafey, Rube Marquard, Ross Youngs, and George Kelly.

Chick Hafey

Hampered by poor eyesight and severe sinus problems, Charles James “Chick” Hafey played just 1,283 games but still managed to amass 1,466 hits and a career batting average of .317. Hafey won one batting title and was named to the inaugural All-Star Game, where he collected the first ever hit in All-Star Game history.

Hafey was one of the first products of Rickey’s farm system, arriving in St. Louis as a rookie in 1924. He was a part of the 1926 Cardinals team that won the World Series, but was limited after suffering several beanings that season. It is believed his health problems were a result of the beanings, and he would become the most prominent player of his era to wear eye glasses. Hafey continued to wear glasses throughout his career.

Leo Durocher

Leo Durocher’s life in baseball began as a small, slick-fielding shortstop with the dynastic New York Yankees of the 1920s. While he was not an imposing hitter, Durocher’s scrappy play and maximum effort led Babe Ruth to call him “the All-American out.”

Durocher won the 1928 World Series with the Yankees, then won another Fall Classic as captain of the St. Louis Cardinals’ “Gashouse Gang” in 1934.

In addition to his hustle, Durocher also garnered his famous nickname “The Lip,” or “Lippy,” for his hard-scrabble conversations with umpires from the dugout. His temper was thought to have stemmed from his relationship with another diminutive Hall of Famer: Rabbit Maranville.

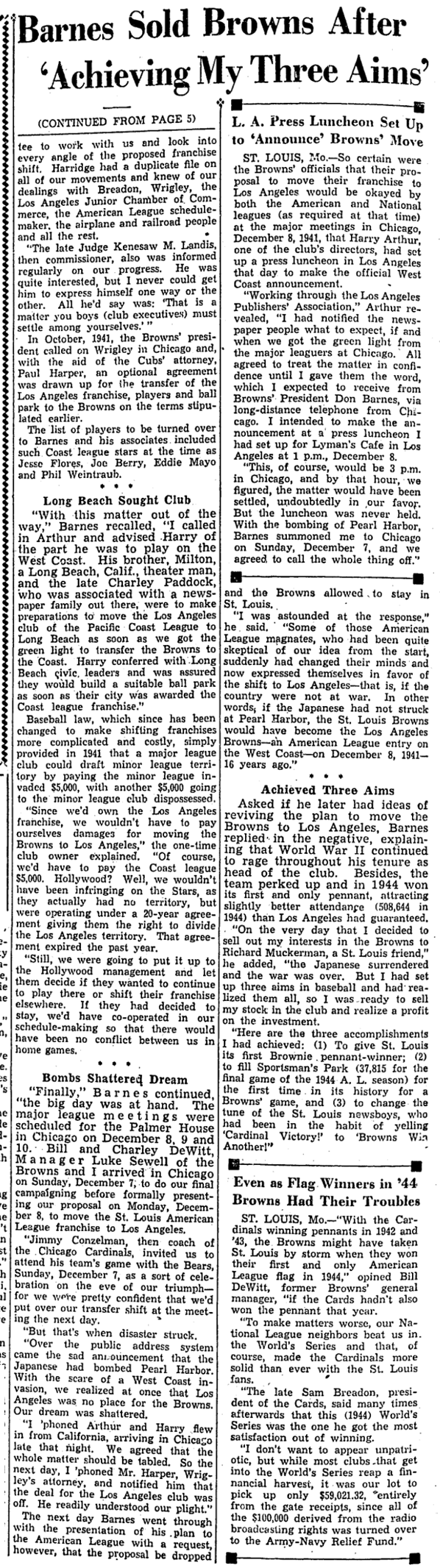

Bob Uecker

This little stunt may have gotten Bob Uecker into some trouble off the field, but it’s one of the lasting images of his time as a colorful character during his playing career.

Dizzy Did It First

30 years before Bob Uecker did it, Dizzy Dean was doing it in 1934.

Dizzy led the Gashouse Gang, winning the MVP in 1934, and leading the National League multiple times over the course of his career in wins, strikeouts, innings, complete games, and shutouts. He led the league with 28 wins in 1935, and was selected to four consecutive All-Star Games from 1934 to 1937. His number 17 is retired by the Cardinals.

Dizzy on the Cubs

Dean won 28 and 24 games in 1935 and 1936 respectively, finishing second in MVP voting in both seasons. In 1937, Dean suffered an injury after being hit in the toe by a line drive during the All-Star Game. Trying to return from the injury too quickly, Dean hurt his arm and largely lost his effectiveness.

Traded to the Cubs in 1938, Dean spent four seasons in Chicago, including appearing in the 1938 World Series, which the Cubs lost to the Yankees.

Johnny Mize

Johnny Mize entered major league baseball in 1936, and soon took on the nickname “The Big Cat” because of the poise in his stance when he was at bat and his ease in the field.

The first baseman really came into his own in 1938, the first of three consecutive spectacular years where he led the National League in total bases every year. He led the NL in slugging percentage with a .614 mark on 1938 to go with a .422 on-base percentage. Mize followed it up in 1939 by winning the batting title with a .349 average. He also led the NL in home runs with 28 and had a .444 on-base mark. In 1940, he was once again the home run leader, this time with 43, and he led the league in RBI. He led in RBI twice more, in 1942 and 1947.

In 15 big league seasons, Mize totaled 2,011 hits, 359 home runs and 1,337 RBI to go with a .312 batting average.

Enos Slaughter

in 1938, Enos Slaughter comes to St. Louis. Slaughter was a bona fide all-star. In 1939, he led the National League with 52 doubles while batting .320. It was the first of four straight seasons in which Slaughter batted .300 or better.

Slaughter missed all of 1943, 1944, and 1945 due to military service, but comes back in 1946 to lead the league in games played and RBI, and finishes third in the MVP race.

The Mad Dash

Slaughter dashed into baseball immortality during Game 7 of the 1946 World Series against the Boston Red Sox. With the score tied 3-3 in the bottom of the eighth inning, Slaughter led off with a single. He remained at first base as the next two batters were retired and then took off to steal second with left fielder Harry Walker at the plate.

Walker stroked a double into center field, and Boston’s Leon Culberson threw the ball to shortstop Johnny Pesky. While Pesky hesitated on the relay, Slaughter kept on running, ignoring third base coach Mike Gonzalez’s stop sign and scoring what proved to be the series-deciding run.

Mort Cooper

Mort Cooper was signed as an Amateur Free Agent in 1933 but he did not make his Major League debut until 1938 when he was 25, after years of battling injuries. The hurler was a middle-of-the-road player from 1939 to 1941, but in 1942 he was phenomenal with a league-leading 22 wins against only 7 losses, and Cooper was also first in the National League in ERA (1.78), Shutouts (10), ERA+ (192) and WHIP (0.987). Cooper was finally an All-Star, and he won the MVP. The season was capped off with a World Series win.

In the following two years, Cooper remained a 20-game winner, was in the top ten in MVP voting, and helped the Cardinals win the NL pennant. The Cardinals won the World Series again in 1944, and Cooper was excellent with a 1.13 ERA.

Stan Musial

The Cardinals ended 1943 with a 105-49 record and clinched the NL pennant for the second consecutive season. Stan Musial hit .357 and won the batting title. He also led the league in batting average, doubles, and triples.

It was the first of his three National League MVP seasons.

Marty Marion

After spending four seasons in the minors, Marty Marion made his big league debut with the Cards in 1940. A sure-fielding shortstop and good hitter, he would anchor the franchise’s infield through 1950.

“Maybe I’m prejudiced because I see him every day,” said Cardinals manager Billy Southworth, who would bestow the nickname Mr. Shortstop on Marion. “But he’s the best ever. Yes, he’s Mr. Shortstop in person. He anticipates plays perfectly, can go to his right or left equally well and has a truly great arm. Some of the things he does have to be seen to be believed. And he’s just as grand a person, too, as he is a ballplayer.”

Marion won the 1944 National League MVP Award by one point over Bill Nicholson of the Cubs.

Farm System

Commissioner Kenesaw Mountain Landis shook the game’s growing player development program when he made free agents of 74 St. Louis Cardinals’ minor leaguers.

On March 23, 1938, Landis set free 74 Cardinals minor leaguers. The players were released from a total of six teams and the owners of these teams were fined $2,176. Landis found that the St. Louis Cardinals were in violation of the working agreements with these minor league clubs.

The 1940s

In the 1940s, a golden era emerged as Branch Rickey's farm system became laden with such talent as Enos Slaughter, Marty Marion, Mort Cooper, Walker Cooper, Max Lanier, Whitey Kurowski, and Johnny Beazley.

The team also got significant contributions from Harry Brecheen and Howie Pollet. It was one of the most successful decades in franchise history with 960 wins and 580 losses for a winning percentage higher than any other Major League team at .623.

Stan Musial

Musial played his entire 22-year career as an outfielder and first baseman for the Cardinals. He is the franchise's career leader in virtually every batting category: games played, at-bats, runs, hits, doubles, triples, home runs, RBI, walks, and total bases.

He has the most walk-off home runs in franchise history and the second-most multiple homer games behind Albert Pujols. His .331 average is fourth in team history. He was a 3-time MVP, and played in four World Series, winning three of them. He won 7 batting titles, and was a 24-time All-Star.

One Of The All-Time Greats

Every time I see some Stan Musial statistics, whether they're from a single season, or his career stats, my immediate thought is "wow, this guy was REALLY good."

My next thought is usually something along the lines of "how does no one ever mention his name among the inner-circle all-time greats?"

I've always just found it strange that his numbers nearly rival Willie Mays and Henry Aaron's, but his name isn't revered like theirs on a national level.

After speaking with some other filmmakers, journalists, and people who either covered Stan or spent time around him during his life and career, Ed hypothesizes that it may just be because he was kind of a boring guy.

In a 2013 article, author Luke Epplin kind of comes to the same conclusion: “Biographers and fans paint the late Cardinals outfielder as the nicest guy in baseball, but that narrative has lessened his longterm legacy when compared with the other greats of his time.”

Musial’s 1948

One of the most accomplished batsmen in big-league history, during a 22-season career that saw him set dozens of records, Musial composed no other 154-game schedule better than that of the Summer of 1948. It marked the closest he ever ever came to winning a Triple Crown:

He led the National League with a .376 batting average, his highest single-season mark and the third of his seven batting titles.

He led the National League with 131 runs batted in, the most he ever drove in during one season – this from the player who had the league record for career RBI until 1971.

He finished third in the league with 39 home runs; Pittsburgh’s Ralph Kiner and New York’s Johnny Mize tied for the NL top honor with 40 homers apiece. Musial hit 475 home runs in his career, but his 1948 total marked his single-season best and was 20 more than his previous season high.

“Why be greedy?” Musial said of missing the Triple Crown. “I had a pretty good year, so why wish for more than I had coming to me? My only regret is the Cardinals didn’t win the pennant.”

1940 Cardinals

The 1940 Cardinals wore two different caps: the interlocking STL, that we’re all incredibly familiar with, and a block STL.

The team has consistently had an interlocking STL on the cap since 1942.

This photo and the images which make up the two graphics below, courtesy of cardinalsuniformsandlogos.com

Billy Southworth wearing the interlocking STL for the 1940 Cardinals

Terry Moore wearing the block STL for the 1940 Cardinals

Pillbox Cap

For the 1976 season, in celebration of the 100th anniversary of the National League, six NL teams wore patches and pillbox style caps.

The Cardinals didn't wear them as their primary cap, but would wear them occasionally, and even painted the pillbox-style horizontal lines on their batting helmets, as well.

Zippered Jerseys

As can be seen in many of the photos within these liner notes, the Cardinals wore zippered jerseys some years. This one, which Stan Musial wore during the 1951 season, sold for $43,200 in August of 2018 via Heritage Auctions.

FDR’s “Green Light Letter” gave Major League Baseball the okay to continue playing after the bombing of Pearl Harbor.

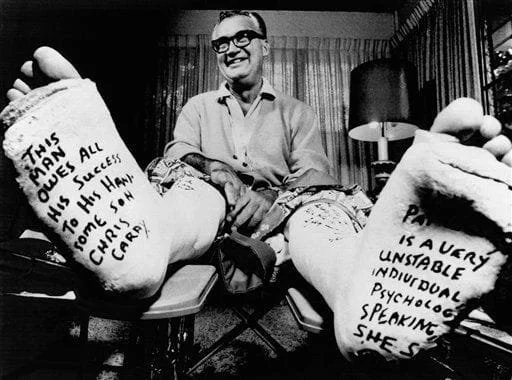

The Browns To Los Angeles?

The St. Louis Browns held Spring Training at Olive Memorial Stadium in Burbank, California from 1949 to 1952, but nearly a decade earlier, the team almost moved to California entirely.

Unable to compete in the American League on the field or with the rival Cardinals off of it, Browns ownership had decided to move the team to Los Angeles for the 1942 season, becoming the first major American professional sports franchise on the West Coast.

The Browns were so certain they were moving that they had even set up a news conference in Los Angeles at Lyman's Cafe. All they needed was for the official vote, which was expected to pass. The Browns would head west, more than 15 years before the Dodgers and Giants ended up doing so.

And so, the vote was scheduled. It was to take place in Chicago on the morning of Monday, Dec. 8, 1941. The news conference in Los Angeles was scheduled for 1 p.m. PT the same day. The Browns would triumphantly introduce themselves to Southern California. Major League Baseball would span coast to coast.

First Home Night Game

On June 4, 1940, the Cardinals played their first night game at home, losing to Brooklyn, 10-1, despite Joe Medwick’s 5-for-5 performance that included three doubles.

However, the honor of hosting the first night game in St. Louis went to the Browns 11 days earlier, on May 24, 1940, after the two teams had finally agreed to split the $150,000 cost of installing lights at Sportsman’s Park.

Streetcar Series

1944 saw perhaps the nadir of 20th-century baseball, as the long-moribund St. Louis Browns won their only American League pennant. Some of the players were 4-Fs, rejected by the military for physical defects (such as one-armed Pete Gray) or limitations that precluded duty.

Others divided their time between factory work in defense industries and baseball, some being able to play ball only on weekends. Some players avoided the draft by chance, despite being physically able to serve. Stan Musial was one. Musial, enlisting in early 1945, missed one season. He rejoined the Cardinals in 1946.

As both teams called Sportsman's Park home, the traditional 2–3–2 home field assignment was used for the 1944 World Series (instead of the 3–4 format, which had been used during wartime).

The 1944 St. Louis Browns

1944 World Series

Stan Musial said it was strange playing in the 1944 World Series because, even though it was taking place in his team’s home park, he felt like the fans were mostly rooting for the underdog Browns, who also used Sportsman’s Park as their home field.

Strikeouts

With a difficult batter’s eye in center field, there were many strikeouts during the 1944 World Series at Sportsman’s Park.

A difficult batter’s eye was one thing that players universally loathed about Wrigley Field in Chicago, as well. The Cubs’ strange and consistent issues with rigging up an acceptable batter’s eye compelled Stan Musial to once call the background “murder,” adding, “and that’s exactly what it will result in one of these days if something isn’t done.”

Joe DiMaggio was so upset this ball was caught during Game 6 of the 1947 World Series, that he went on a crusade to have the style glove worn by Al Gionfriddo outlawed - despite the fact that Joe wore the same style glove.

Satin Uniforms

For the 1946 season, the Cardinals ordered red, satin uniforms. Satin uniforms were briefly used by a handful of MLB teams in the late 1940s to enhance fan viewing with the advent of night games, because it was believed that the reflective quality of the satin would be beneficial to fans viewing the game.

But when Cardinals players saw the uniforms, they said they looked like lingerie, and didn’t want to wear them. The newspaper went on to say the Cardinals sold their red satin suits to a local teen baseball team, and never wore them in the big leagues.

Satin Uniforms

The Cardinals Museum obtained a silver-gray satin jersey, marked for the 1948 season, so it appears that the team didn’t immediately give up on the idea of playing in shiny uniforms.

Pictured here is a rare satin jersey with all the official logo embroidery and trim, manufactured by Rawlings in St. Louis. “Satins” were briefly used by a handful of MLB teams in the late 40’s to enhance fan viewing with the advent of night games. It was believed that the reflective quality of the satin would be beneficial to fan viewing the game.

Apparently they were extremely short-lived and it is thought that the players disliked them.

1956 Script Uniforms

There is just something inherently wrong about a Cardinals uniform without the birds on the bat. The 1956 Cardinals uniforms look like a movie wanted to have a Major League team depicted, but couldn’t afford the rights to use the actual uniforms, so they made these knock-off jerseys and thought “that’s close enough, right?”

Baggy Uniforms

There’s just something about the way the Cardinals wore their uniforms in these days. A little loose-fitting. A little baggy. With the pants pulled up over the knee, but with enough material that it still kind of folded down and draped over, even with the socks staying exposed.

Here, Red Schoendienst, Enos Slaughter, Marty Marion, Stan Musial, and Whitey Kurowski look the part.

Red Schoendienst

Another player to become a success on the Cardinals out of Branch Rickey’s farm system was Red Schoendienst. He joined the club in 1945 to fill in for Stan Musial in Left Field while Stan was serving in the U.S. Navy. Red batted .278 with 47 RBI and a National League-leading 26 stolen bases.

The following year, Stan returned to the Cardinals, and Red moved to third base and then shortstop before settling in at second base. St. Louis won the World Series over the Boston Red Sox, and Red began to develop into one of the best hitting and fielding second basemen of all time.

Red & Stan

Not only were they teammates for 14 years, they were also roommates. A truly special bond. When Schoendienst was inexplicably traded in 1956, Stan was visibly upset.

“The rest of us got the word that Red had been traded just as we were boarding a train out of St. Louis for an eastern trip,” he wrote in Schoendienst’s 1998 autobiography. “It was the saddest day of my career. I slammed the door to my train berth shut and didn’t open it for a long time.”

Asked by the Associated Press to comment on the trade, Stan Musial, Schoendienst’s friend and road roommate, responded with a rare, “No comment.”

Red’s Impact

Red wore a Cardinals uniform for 45 seasons as a player, coach, and manager, and was involved with the organization for a total of 67 years.

His number 2 was retired by the team in 1996.

George Kissell

You can’t really talk about The Cardinal Way without bringing up George Kissell. He spent 10 years in the minor leagues as an outfielder and served the Cardinals in several capacities after joining the organization in 1940. From 1946 to 1968, he worked as a manager, coach, scout and minor league instructor. Kissell was a Cardinals’ coach from 1969 to 1975.

José Oquendo

As a player, José Oquendo was known for his versatile defense: he played primarily second base and shortstop, but also frequently in the outfield, and made at least one appearance at every position. Oquendo has the second-highest career fielding percentage for second basemen (99.19%), behind only Plácido Polanco's career mark of 99.27%.

As of 2025, Oquendo served as Minor League Infield Coordinator of the St. Louis Cardinals, an organization with whom he has been affiliated since 1985. He managed the Puerto Rico national team in the 2006 and 2009 World Baseball Classics.

Honoring George Kissell

The Cardinals top player development award is named after Kissell, as is the quad in Jupiter, Florida where the minor leaguers compete. A permanent plaque outside the Jupiter clubhouse reads, in part: “Every player in the Cardinals’ Organization since 1940 has had contact with George Kissell and they have all been better for it … Well known for his emphasis on fundamentals, George taught several generations of Redbirds how to play baseball.”

Bill Veeck

A messy divorce caused Bill Veeck to have to sell his shares of the Cleveland Indians in 1949. He bought the St Louis Browns in July of 1951 with the same intent as the American League team had when they moved to St Louis in 1902: to run the Cardinals out of town.

The Cardinals had won three World Series in the 1940s, and six since 1926, yet it wasn’t out of the realm of possibility that the Browns could do it.

Cardinals To Detroit?

On March 28, 1935, during spring training in Bradenton, Florida, Sam Breadon told reporters he would move the Cardinals to Detroit if Tigers owner Frank Navin (seen here) approved.

The 1934 Tigers had a regular-season attendance of 919,161 - nearly three times the Cardinals’ total - and Breadon saw the job-generating Motor City as a town better suited than St. Louis to support two major-league franchises.

Sid Keener, sports editor of the St. Louis Star-Times, reported, “Breadon intimated that he would make overtures to the two major leagues during the coming season to rearrange the current setups of the National and American leagues. He said he believed baseball would profit by changing St. Louis to a one-club major league city, leaving the Browns as the sole representative in the Missouri city and by moving his own National League franchise to Detroit.”

Cardinals To Houston?!

As baseball laid dormant in the winter of January 1953, Cardinals owner Fred Saigh was mulling over his future. He’d just gotten out of a six month stay at the Federal Penitentiary in Terre Haute, Indiana, in November on parole after pleading no contest to tax evasion.

It was likely if the Cardinals weren’t sold by the next Owner’s Meeting that he’d be formally banned from baseball for life (this happened to former Phillies Owner William D. Cox in 1943 after he was found to be gambling on baseball) in which case he’d suffer public humiliation and be forced to sell anyways and possibly to a buyer not of his choosing.

Saigh would choose to sell the team prior to action from the National League and return to life away from sports and the public eye. The strongest and most serious offers had come from two groups of businessmen from Houston, Texas, they both planned to move the team to Houston by the 1954 season as the Cardinals already owned the rights to that market through their Minor League Affiliate the Houston Buffalos (later Buffs).

Anything Could Happen

On September 30th, 1951, St. Louis Browns fans had quite a day. After seeing Ned Garver win his 20th game, they were treated to a show by the Harlem Globetrotters, who set up a basketball court on the field at Sportsman’s Park after the baseball game concluded.

Being at a Browns game, especially during the years when the team was owned by Bill Veeck, was like being at a circus. You never knew what was going to happen.

Eddie Gaedel

One of Veeck’s most memorable stunts was sending 3’7” Eddie Gaedel to the plate in a game between the Browns and the Tigers in August of 1951. Bob Cain had the impossible task of trying to throw a strike to a man with a 1.5” strike zone.

Grandstand Managers Day

This 1951 stunt saw Veeck hand out signs to fans at Sportsman’s Park in St. Louis which said “YES” on one side, and “NO” on the other, and the game’s managerial decisions were put up to a fan vote.

August 24, 1951: St. Louis Browns Fans Manage To Get It Right In Veeck Promotion - SABR article

1.000 OBP

Eddie salutes the crowd after his one and only game in Major League Baseball, playing for Bill Veeck’s St. Louis Browns.

August 24, 1951

Despite the fact that the Browns somehow won this game (even though the Athletics knew every move the team was going to make before they made it??), Connie Mack was entertained by Veeck’s stunt at Sportsman’s Park.

August Busch

On February 20th, 1953, August "Gussie" Busch Jr., of Anheuser-Busch, bought the Cardinals for $3.75 million, according to KSDK. This acquisition ensured the Cardinals would remain in St. Louis, preventing them from being sold to out-of-town interests.

Much like Chris von der Ahe had done half a century earlier, Auggie Busch bought the St. Louis ballclub because he thought it would be a great way for him to sell a lot of beer.

Busch Stadium

The story goes that Gussie Busch created Busch Beer as a middle finger to Major League Baseball after they refused his proposal to rename Sportsman’s Park as “Budweiser Stadium” because they didn’t want the association with beer or alcohol. Busch agreed, told them he would name the stadium after himself, “Busch Stadium,” and then shortly thereafter, announced a new beer: Busch Bavarian Beer.

“This story is highly possible. It makes logical sense, and it’s a fantastic story,” says Neil Reid, the man behind TheBeerProfessor and professor of geography and planning at the University of Toledo. However, Reid notes, there is a lack of factual evidence to support this claim, although Busch Lager was introduced in 1955, followed by Busch Bavarian Beer the following year — several years after the park was purchased and named.”

“[The stadium] was known as Sportsman’s for 75 years, then Budweiser Stadium for 24 hours, to be renamed Busch Stadium the next day,” she says. “Fans are still known to refer to it as Sportsman’s Park.”

Harry Caray

Harry Caray was the Cardinals broadcaster from 1945 to 1969. In November 1968, Caray was nearly killed after being struck by an automobile while crossing a street in St. Louis; he suffered two broken legs in the accident, but recuperated in time to return to the broadcast booth for the start of the 1969 season.

Recovery

Gussie Busch, the Cardinals' president and then-CEO of Anheuser-Busch, who owned the Cardinals, spent lavishly to ensure Caray recovered, flying him on the company's planes to a company facility in Florida to rehabilitate and recuperate.

On Opening Day of the 1969 season, fans cheered when Harry dramatically threw aside the two canes he had been using to cross the field and continued to the broadcast booth under his own power.

Jack Buck