0501 - Larry Lester & Stephanie Liscio

Larry Lester and Stephanie Liscio are two of the world’s leading authorities on the Negro Leagues, each of whom are published authors, public speakers, researchers, and historians. During our conversation, they referenced a handful of things and people upon which you may want to do more research. Consider this page to be your “liner notes” for the episode so you can follow along.

Larry Lester, Stephanie Liscio, and me, after recording our interview at Cleveland’s historic League Park

Artistic Integrity Records

This episode is brought to you by the Chicago-based record label Artistic Integrity Records.

Email Artistic Integrity Records

Follow Artistic Integrity Records on social media:

“Nancy Faust At The Game”

Nancy Faust, the legendary sports organist who played at White Sox games for 41 years, was our guest for Episode 1 of Season 4. You can listen to that episode HERE.

Her 1978 debut album “Nancy Faust At The Game” has been painstakingly restored and remastered, and is available for the first time in nearly 50 years thanks to Artistic Integrity Records. You can buy a CD copy either signed by Nancy or unsigned HERE.

Cleveland’s Historic League Park

League Park is the former home of the Cleveland Spiders, Blues, Bronchos, Naps, and Indians from 1891 through 1946.

It was the site of John Clarkson’s 300th career win in 1892, and of Games 1 through 3 of the 1895 Temple Cup, which ended with Hall of Famers Cy Young, Jesse Burkett, and the Cleveland Spiders as the Champions of the National League.

Addie Joss

Addie Joss threw a perfect game at League Park in 1908, and after he passed away in 1911, League Park was the site of what was essentially the first ever Major League All-Star Game when a benefit game was held to raise money for his family.

League Park

Napoleon Lajoie collected his 3,000th career hit at League Park in 1914, and it was the site of the incredibly significant Game 5 of the 1920 World Series, which saw the first ever home run by a pitcher in a World Series game, the first ever grand slam in a World Series game, and the first – and to this day, only – unassisted triple play in a World Series game.

Feats of Strength

Walter Johnson got his 3,000th career strikeout at League Park in 1923, and Tris Speaker got his 3,000th hit there in 1925.

Babe Ruth hit his 500th career home run over League Park’s right field fence in 1929, and Joe DiMaggio got the last hit of his 56-game hitting streak there in 1941.

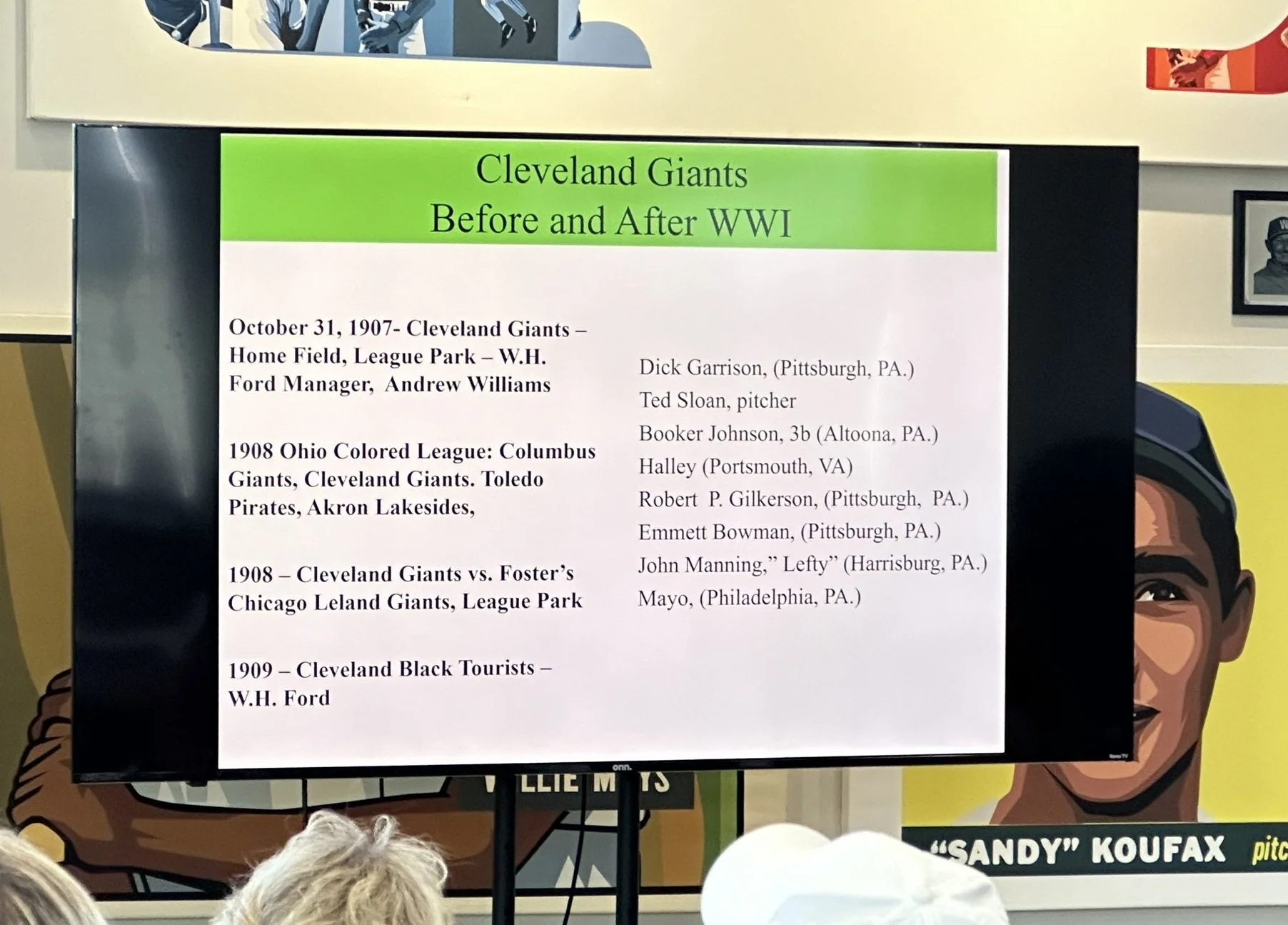

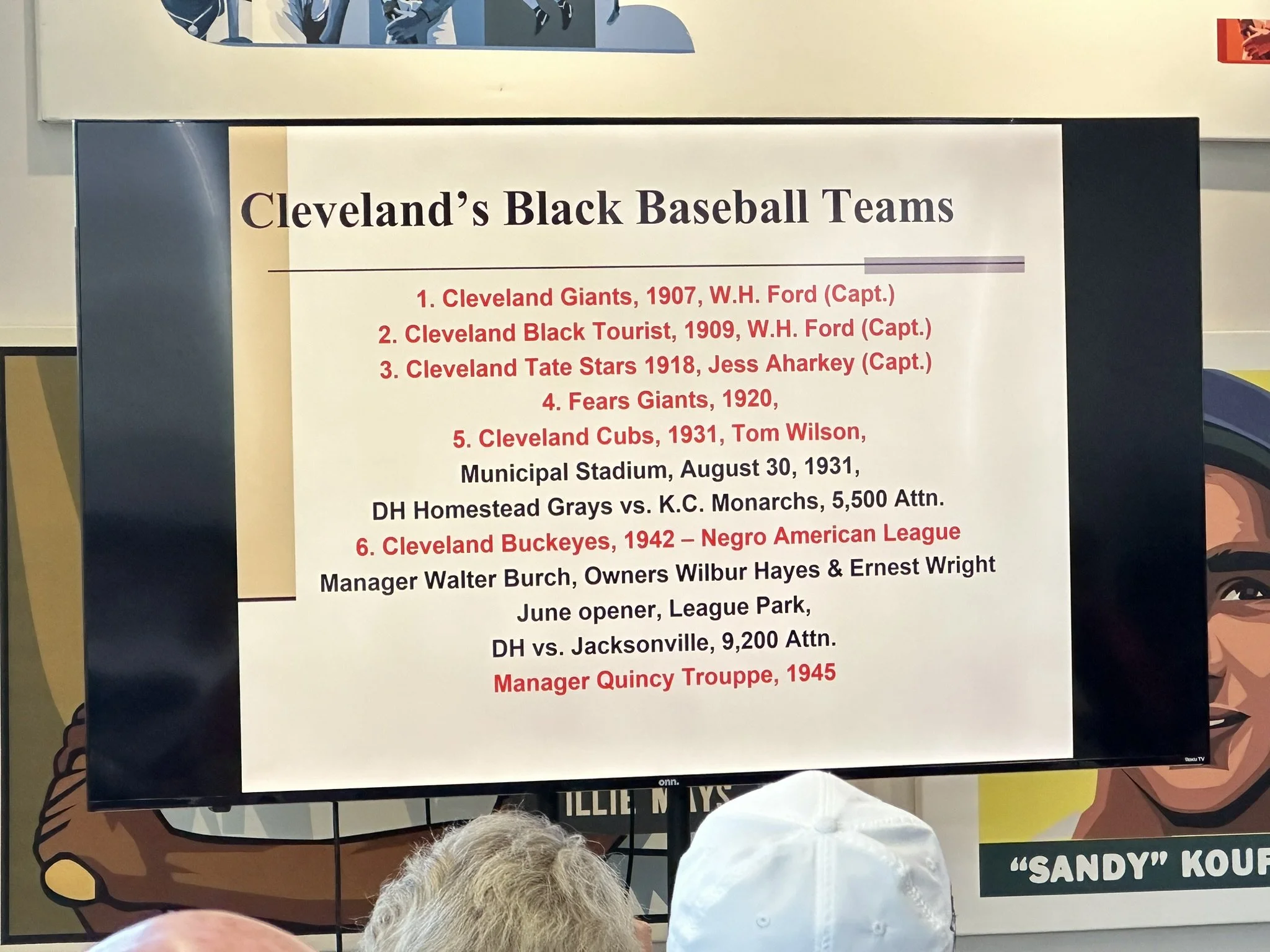

A Long History of Black Baseball

League Park hosted games played by Black baseball teams as early as 1907 when W.H. Ford’s Cleveland Giants called it home, but the most famous Black baseball team to play at League Park was the Cleveland Buckeyes, who called it home from 1942 through 1948, and then again for the first two months of the 1950 season after the team moved to Louisville for 1949.

Cleveland Buckeyes

League Park was the site of Game 2 of the 1945 Negro League World Series between the Cleveland Buckeyes and the Homestead Grays, and the site of the clinching Game 6 of the 1947 Negro League World Series between the Buckeyes and the New York Cubans.

Hall of Famers at League Park

In addition to all of these great moments, the list of incredible players who have stepped on that field is incomprehensible. Literally dozens of Hall of Famers, both Black and white, have participated in games at League Park over the years. And not just players, either, but also umpires and managers.

League Park’s Architecture

Brian Powers is an architect based out of Chicago who has digitally recreated a handful of ballparks from the early 1900s based on their original blueprints, which he has personally collected. He was our guest for Episode 5 of Season 4. You can listen to that episode HERE.

League Park Today

Today, League Park is owned and maintained by the City of Cleveland, and it was thanks to the city’s Division of Recreation that we had access to the Visitor Center to record the panel discussion you’re about to hear.

Thank you to Mike Sierputowski and Ralph King (pictured, on the left) for helping to make that happen.

Thank you, also, to Chuck Carter (pictured, on the right), who is the head groundskeeper at League Park. He makes everything look beautiful there and run smoothly.

You can rent the field at League Park, or the Visitor Center (or both), for your own event! In 2024, I hosted an 1860s style vintage base ball game on the field, and it couldn’t have been a better experience. If you want to host an event there, fill out your permit application HERE.

Stephanie Liscio

Stephanie Liscio is the author of Integrating Cleveland Baseball: Media Activism, the Integration of the Indians, and the Demise of the Negro League Buckeyes. You can buy her book HERE.

Stephanie is a member of the leadership team in Cleveland’s Jack Graney Chapter of SABR, and has contributed essays to a number of SABR publications, as well as to the Black Ball Journal.

She completed her Ph.D. in history at Case Western Reserve University, where she wrote a dissertation on stadiums and community after World War II.

In addition to her baseball-related research, Stephanie has worked as a researcher for University Hospitals’ 150th anniversary celebration, for the National Museum of Organized Crime and Law Enforcement in Las Vegas, and has contributed to several documentary films.

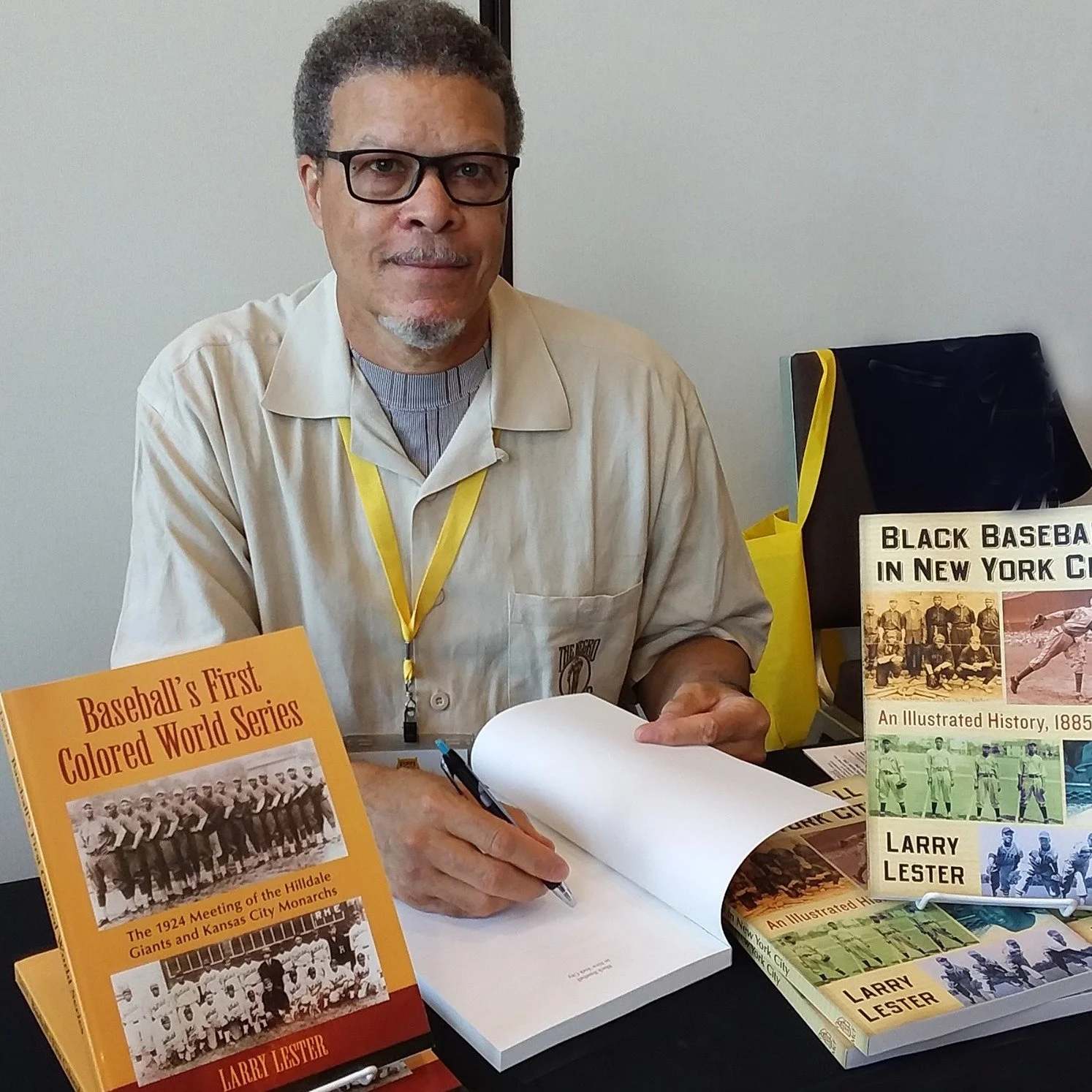

Larry Lester

Larry Lester is an esteemed author, historian, and consultant in film and museum curation. He is renowned for his lifelong dedication to preserving African American history, particularly through the lens of sports and cultural heritage.

Larry is the former chairman of the Society for American Baseball Research's Negro League Committee. He co-founded the Negro Leagues Baseball Museum in Kansas City, and served as its Research Director, Senior Editor, and Treasurer from 1991 to 1995.

In 2006, Larry chaired the Hall of Fame's Special Negro Leagues Committee, selecting a record 17 new Negro League players, executives, and managers—an unprecedented recognition of their contributions.

He is listed as a contributing researcher to more than 220 publications on African American history, and has authored, co-authored, or edited numerous books about Black Baseball history.

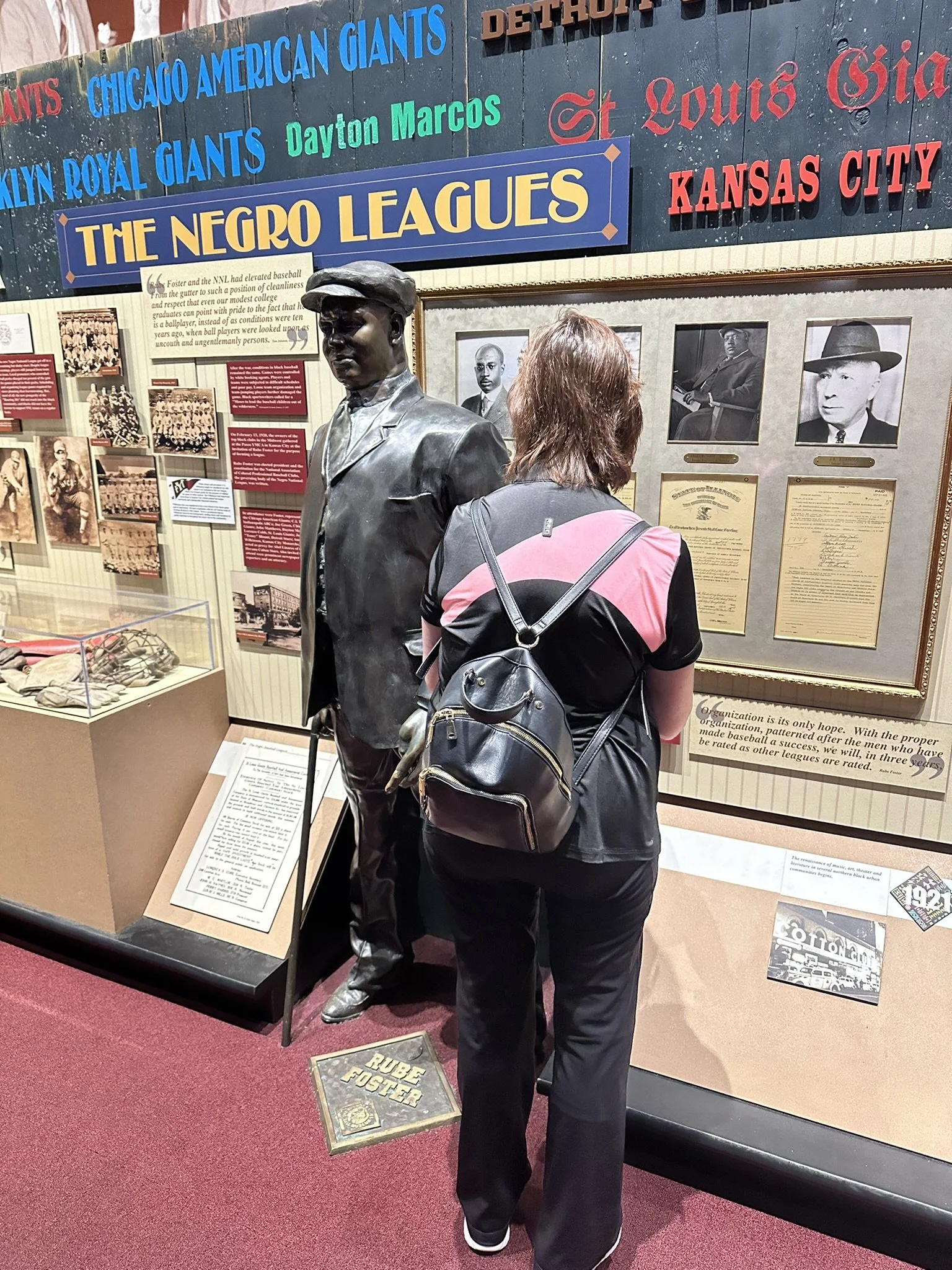

Negro Leagues Baseball Museum

With Buck O’Neil, Slick Suratt, and Phil Dixon, Larry Lester co-founded the Negro Leagues Baseball Museum in Kansas City.

Phil Dixon is also an incredible Negro Leagues researcher, interviewer, and historian with over 40 years experience in the field. Phil was our guest for Episode 4 of Season 1. You can listen to that episode HERE.

Larry Lester’s pioneering stats project has since been augmented by the efforts of others, notably the Seamheads group, with which MLB launched its first iteration of the integrated historical database, including more than 2,300 players from the Negro Leagues.

A Live Podcast Recording!

This episode was recorded in front of a live audience at League Park on August 6, 2025.

While we do touch on Black baseball topics dating back to the 19th century in this discussion, Larry, Stephanie, and I primarily focus on the Negro Leagues in the 1940s during this interview, the last great decade of the Negro Leagues.

Ticket House

League Park’s original ticket house at the corner of 66th and Lexington in the Hough neighborhood in Cleveland is still standing.

Fannie Lewis was the Ward 7 representative for the Cleveland City Council, an area which includes the Hough neighborhood, for almost thirty years. During her tenure, Lewis earned a reputation for her tireless efforts to improve the community in the wake of the 1966 Hough Riots.

Chuck Carter

Chuck Carter has been a fixture in the Black communities of Cleveland since 1962, when he and his family moved to the area.

Taking cues from his mother’s civil rights activism, Chuck became a community leader and managed the Glenville Rec Center for years, creating initiatives to get the youth involved in multiple sports.

Chuck has been the head groundskeeper at League Park for years, and continues his tireless efforts to enrich his community any way he can.

This was our setup in League Park’s Visitor Center the night we recorded this panel discussion.

Stephanie Liscio

Stephanie’s book Integrating Cleveland Baseball: Media Activism, the Integration of the Indians and the Demise of the Negro League Buckeyes is available to purchase HERE.

Jackie Robinson

I promise it wasn’t planned that my seat would be directly in front of the Michael Jordan and Jackie Robinson collages on the walls of the Visitor Center. But I wasn’t going to rearrange any tables or chairs to change it, that’s for sure.

Moses Fleetwood Walker

Moses Fleetwood Walker played for semi-professional and minor league baseball clubs before joining the Toledo Blue Stockings of the American Association for the 1884 season. Because of the American Association’s distinction as a “major” league, Walker is often credited with being the first Black man to play major league baseball.

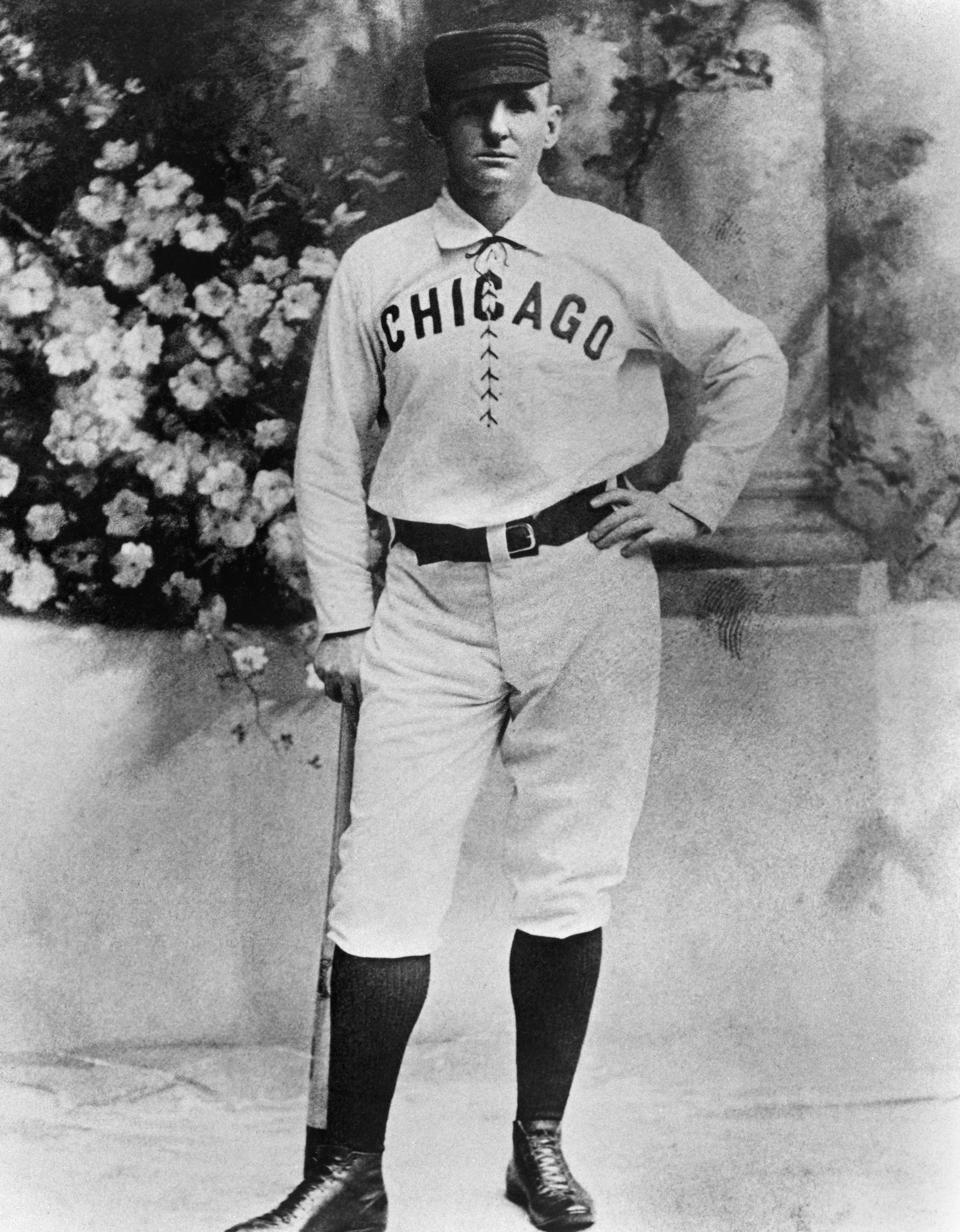

Cap Anson

Adrian Constantine “Cap” Anson was regarded as one of the greatest players of his era and one of the first superstars of the game. Anson was one of baseball's first great hitters, and one of the first to tally over 3,000 career hits. In addition to being a star player, he innovated managerial tactics such as signals between players and the rotation of pitchers.

Anson played a role in establishing the racial segregation in professional baseball that persisted until the late 1940s. On several occasions, Anson refused to take the field when the opposing roster included Black players. Because of his standing in the game, other players, managers, and teams felt emboldened to follow his lead. On July 14, 1887, the owners of the International League voted to ban the signing of new contracts with black players.

“Gentleman’s Agreement”

African-Americans played in the Major Leagues in 1878 and between 1884 and 1887. Still, racist thinking persisted and Major League club owners again came to what can only be described as a “gentleman’s agreement” banning African-American players from the Major League.

While no documentation exists, no contracts were extended to African-American players between 1888 and 1945.

Bismarck, ND

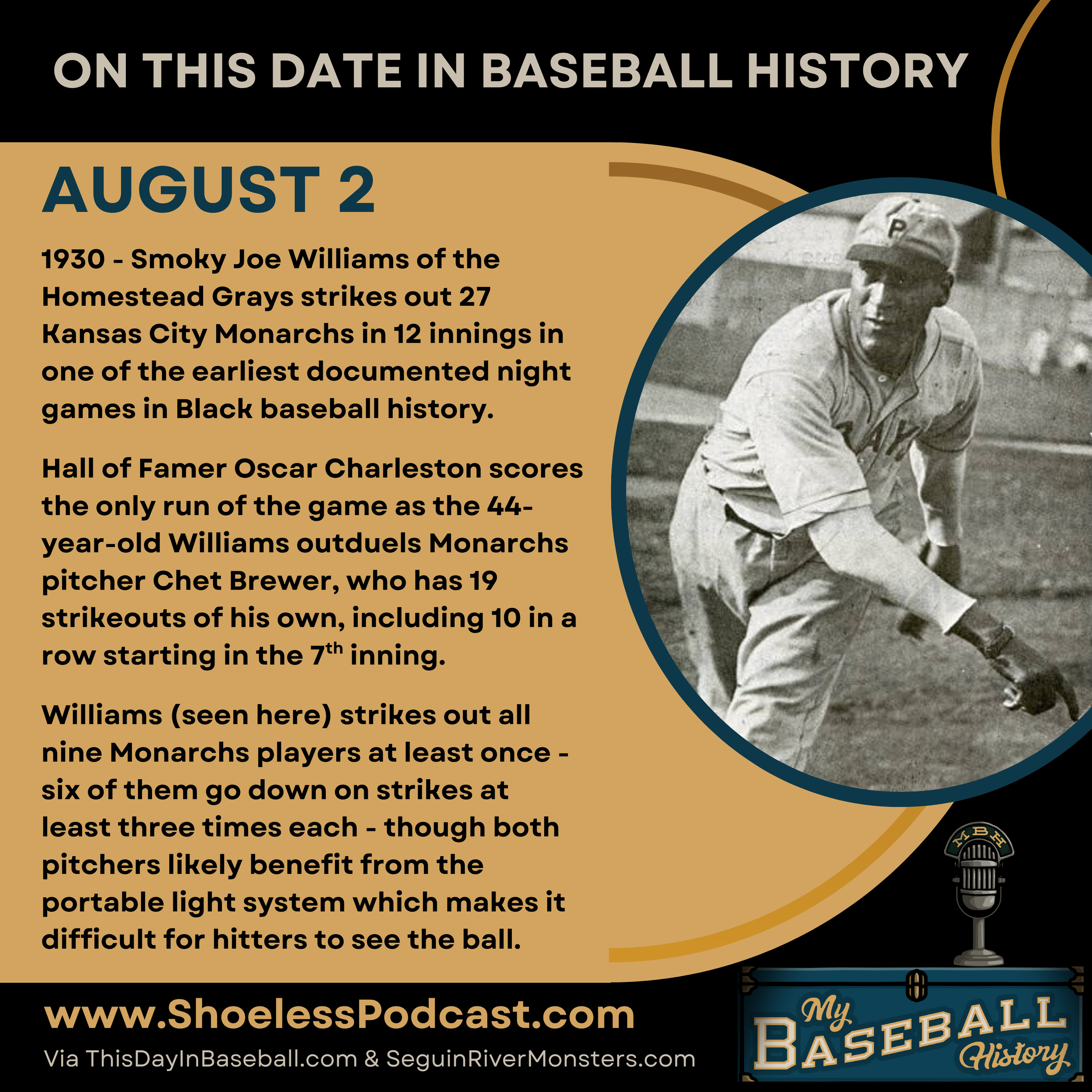

During Satchel Paige’s brief 1933 stay in North Dakota, he struck out 119 batters in 72 innings and was a perfect 7-0.

Paige’s most significant win for Bismarck was a 10-inning 3-2 Labor Day weekend win at Jamestown, in which he bested 1996 Hall of Fame inductee Bill Foster, whom Jamestown had brought in from the Chicago American Giants expressly to oppose Paige.

Neil Churchill

Neil Churchill (seen here, bottom row, center) was a car dealer in Bismarck, North Dakota who funded an integrated baseball team in the mid-1930s, more than a decade before Jackie Robinson broke the color barrier in Major League Baseball.

Churchill teamed up with Abe Saperstein, the owner of the Harlem Globetrotters and personal friend of Churchill, to attract Negro League legend Satchel Paige along with three other Negro League players to his team in 1933. The team went on that year to claim the state championship, and the Bismarck Churchills won the very first NBC World Series in 1935.

The Bob Feller/Satchel Paige barnstorming tour following the 1946 season made stops in 32 United States cities over 27 days, including a game at Los Angeles' Wrigley Field, as advertised in the Oct. 16, 1946, Los Angeles Times. (courtesy of the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum)

Kenesaw Mountain Landis

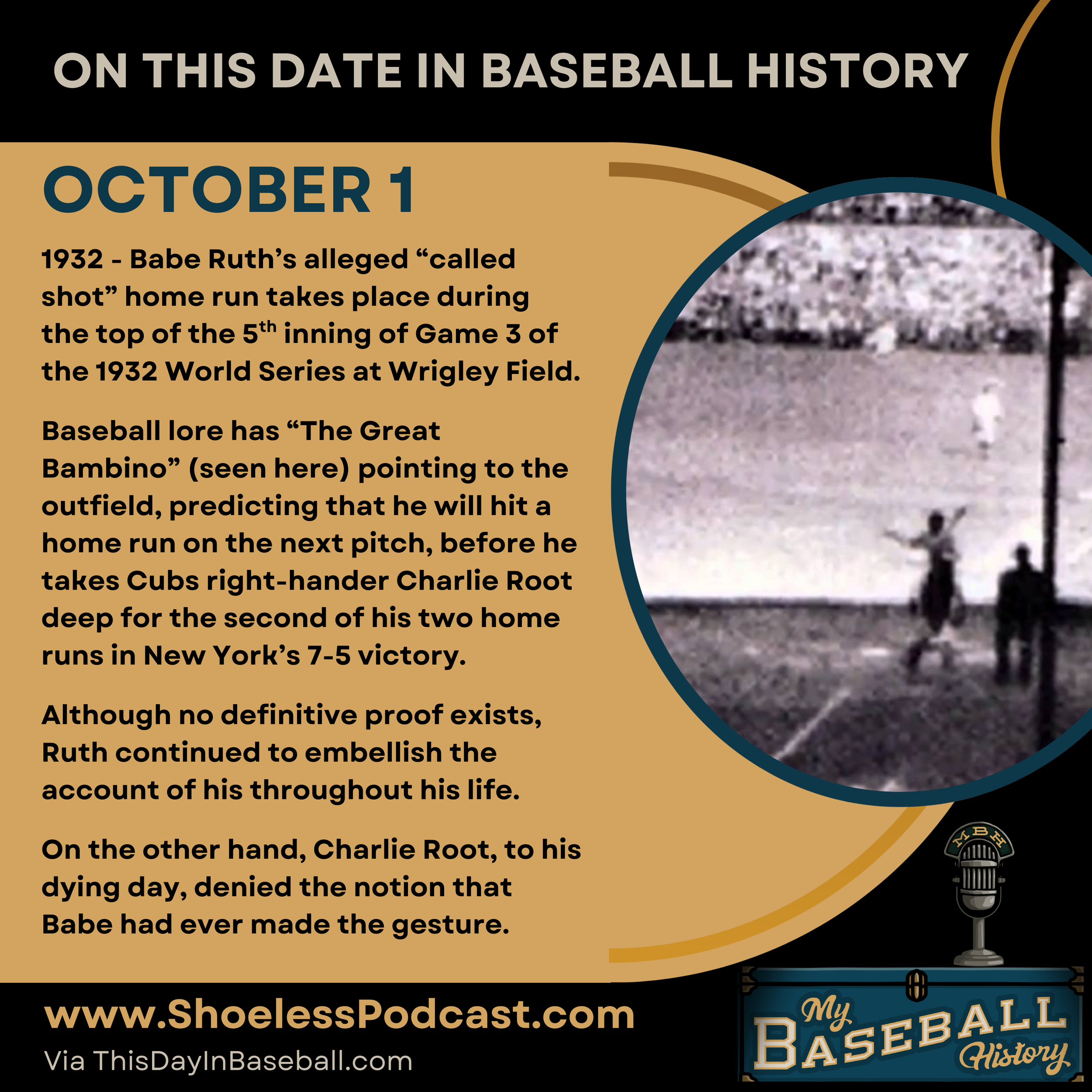

There is speculation that one of the reasons Babe Ruth was never offered a managerial position in Major League Baseball after his playing career was over is because Commissioner Kenesaw Mountain Landis told teams not to hire him.

Landis felt because of Babe’s history in barnstorming, and his knowledge of the great Black baseball players of the time, that he would have brought the best Black players to a team if he were its manager, and integrated baseball long before Jackie Robinson broke the color barrier in 1947.

Babe Ruth

Babe Ruth was incredibly familiar with the great Black players of the day because of his extensive barnstorming during the offseasons.

Babe’s All-Stars lost to the Kansas City Monarchs during a postseason series in 1922, which infuriated Commissioner Landis.

Kenesaw Mountain Landis presided over Major League Baseball from 1920 through 1945. He issued a ruling that said full Negro League teams could not play games against full white Major League teams.

Ruth continued to barnstorm against Black players and teams (much to the delight of Black fans), and happily paid the fines levied by Landis for doing so.

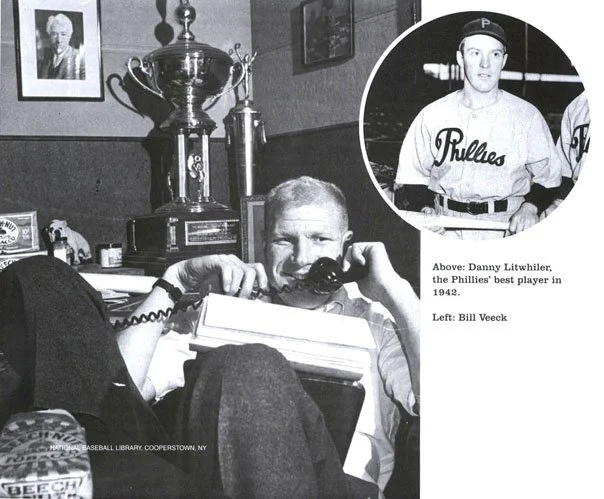

1942 Phillies

Bill Veeck wrote that he tried to buy the bankrupt Philadelphia Phillies after the 1942 season, and intended to stock the team with black players, breaking organized baseball’s color line three years before Jackie Robinson signed with the Dodgers.

In his 1962 autobiography, Veeck asserted that he had lined up financing and enlisted the promoter Abe Saperstein, owner of the Harlem Globetrotters, to help sign Negro Leagues stars. Veeck said he informed Commissioner Kenesaw Mountain Landis of his plan as a courtesy, but that Landis and National League president Ford Frick thwarted him by arranging a quick sale of the Phillies to another buyer.

Larry Doby

The controversial story about Bill Veeck potentially buying the Philadelphia Phillies with the intent to integrate the team has been debated for years as to whether it was true, but Veeck did end up breaking the color barrier in the American League in 1947 by signing Larry Doby.

Paige and Veeck

Not just a publicity stunt, Veeck signed the great Satchel Paige in 1948. The team went on to set an attendance record that season, but whether it was 2.6 million (officially) or 3.4 million (unofficially) is up for debate.

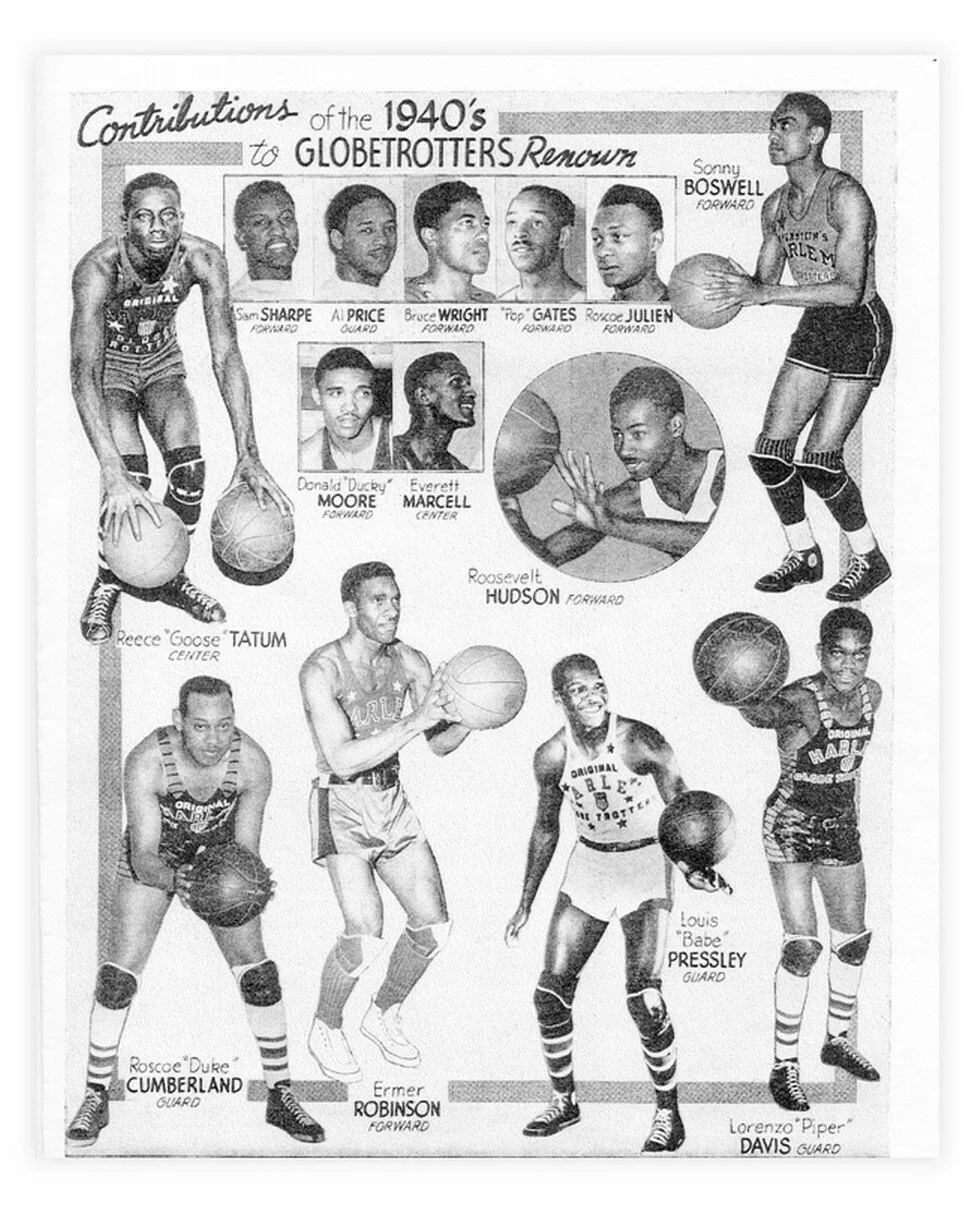

Harlem Globetrotters

The 1940 World Professional Basketball Tournament was held in Chicago in March of 1940 and featured 14 teams.

The tournament gained a local interest when the Chicago Bruins of the NBL made it to the championship round after they beat the ABL's Washington Heurich Brewers in the semifinal round.

The world famous Harlem Globetrotters (who were originally based in Chicago at the time before moving to New York and then Harlem permanently) made it to the championship round over the defending champion New York Renaissance.

The Globetrotters won their first World Basketball Championship, defeating the Chicago Bruins.

Pittsburgh Pirates

The Pittsburgh Pirates played in the same city as the Negro League’s Pittsburgh Crawfords and Homestead Grays, each of whom were dominant teams with multiple Hall of Fame players. Despite this proximity to Black excellence, the Pirates would not integrate until 1954.

From 1939 through 1954, the Pirates went a combined 1,090-1,364-25 (.44473 winning percentage). The only time they finished better than 4th in the National League during that span was in 1944, when teams were playing with short rosters due to World War II.

Logo courtesy of SportsLogos.net

Jackie Robinson, Football Star

In their first year under head coach Edwin C. Horrell (after 14 years under William H. Spaulding as head coach), the 1939 UCLA Bruins compiled a 6–0–4 record (5–0–3 conference), finished in second place in the Pacific Coast Conference, played #3-ranked USC to a scoreless tie, and were ranked #7 in the final AP Poll.

In the fall of 1939, Jackie Robinson enrolled at UCLA, where the student population was less than 1% African-American and there was not a single Black faculty member. He became the first Bruin at the Westwood campus to letter in four sports and was a genuine star in three of them - football, basketball, and track. Baseball was his worst sport at UCLA.

Kenny Washington

Kenny Washington rushed for 1,914 yards in his college career, a school record for 34 years. He was one of five African-American players on the 1939 UCLA Bruins football team, the others being Woody Strode, Jackie Robinson, Johnny Wynne, and Ray Bartlett.

This was a rarity to have so many African Americans when only a few dozen at all played on college football teams. The Bruins played eventual conference and national champion USC to a 0–0 tie with the 1940 Rose Bowl on the line.

UCLA teammates have commented how strong Washington was when confronted with racial slurs and discrimination.

Washington was the first African-American to sign a contract with a National Football League team in the modern (post-World War II) era.

College football would dominate the front page of the newspapers in the 1930s during the season, even in October while the World Series was going on.

1942 East-West All-Star Game

One of the earliest battlegrounds for integration was a Negro Leagues All-Star contest in Cleveland in 1942. That summer, MLB Commissioner Kenesaw Mountain Landis claimed that there was no formal ban on African-Americans in baseball and that it was up to individual team owners to sign black players.

This encouraged a number of African-American journalists to take the lead, but as had been evidenced by the prior half-century, no owners were exactly champing at the bit to be a trailblazer.

Sam Jethroe

The writers at the Cleveland Call and Post, an African-American weekly newspaper in the city, used Landis’s statement as the basis for their sales pitch to Indians owner Alva Bradley, who had been team president since 1927. When the paper asked Bradley about the commissioner’s comments, he echoed Landis by saying any owner could sign a black player at any time, and added that the Indians would consider it. (The Call and Post also reached out to Indians player-manager Lou Boudreau, who said that he supported the integration of the team, but would leave that decision up to Bradley.)

Bradley managed to avoid and deflect specific questions about scouting Negro Leagues games, including the annual East-West All-Star Game. At one point Bradley claimed that “No Negro players have contacted me in any way,” and implied that he would not offer a tryout until a player formally asked for one.

Almost immediately, the Call and Post proposed three players on the Negro American League’s Cleveland Buckeyes that they believed could cut it in MLB: outfielder Sam Jethroe, third baseman Parnell Woods, and pitcher Eugene Bremer.

Parnell Woods

John Fuster, one of the writers with the Call and Post, got permission from Buckeyes GM Wilbur Hayes to use the upcoming East-West All-Star Game in Cleveland as a “tryout” for Jethroe, Bremer, and Woods, since all three men would be on the roster. They penned a formal invitation to Bradley, and the request was signed by Parnell Woods, the only one of the three men who had a college degree.

Bremer had a rough night, as he walked four and allowed five earned runs, and was knocked out of the game by the third inning, departing with the bases loaded. Jethroe and Woods managed to score the West’s lone runs, but only reached base due to a fielder’s choice and an error, respectively. Woods went hitless on the night, and let two balls past him at third base, while Jethroe dropped a routine fly ball and went hitless until a single in the ninth inning with the bases empty. If it was indeed a real tryout, it was truly the worst possible scenario for all three players.

“They Just Don’t Stack Up…”

After the game, Indians owner Alva Bradley addressed Fuster, an account that was published in the Call and Post, and said “We have scouted these men… we saw them play at the Stadium on the night of August 18th, and frankly, Mr. Fuster, they are not big-league material. Why, not one of them got a hit…and the pitcher, Bremer, was knocked out of the box. They just don’t stack up as material for the Indians.”

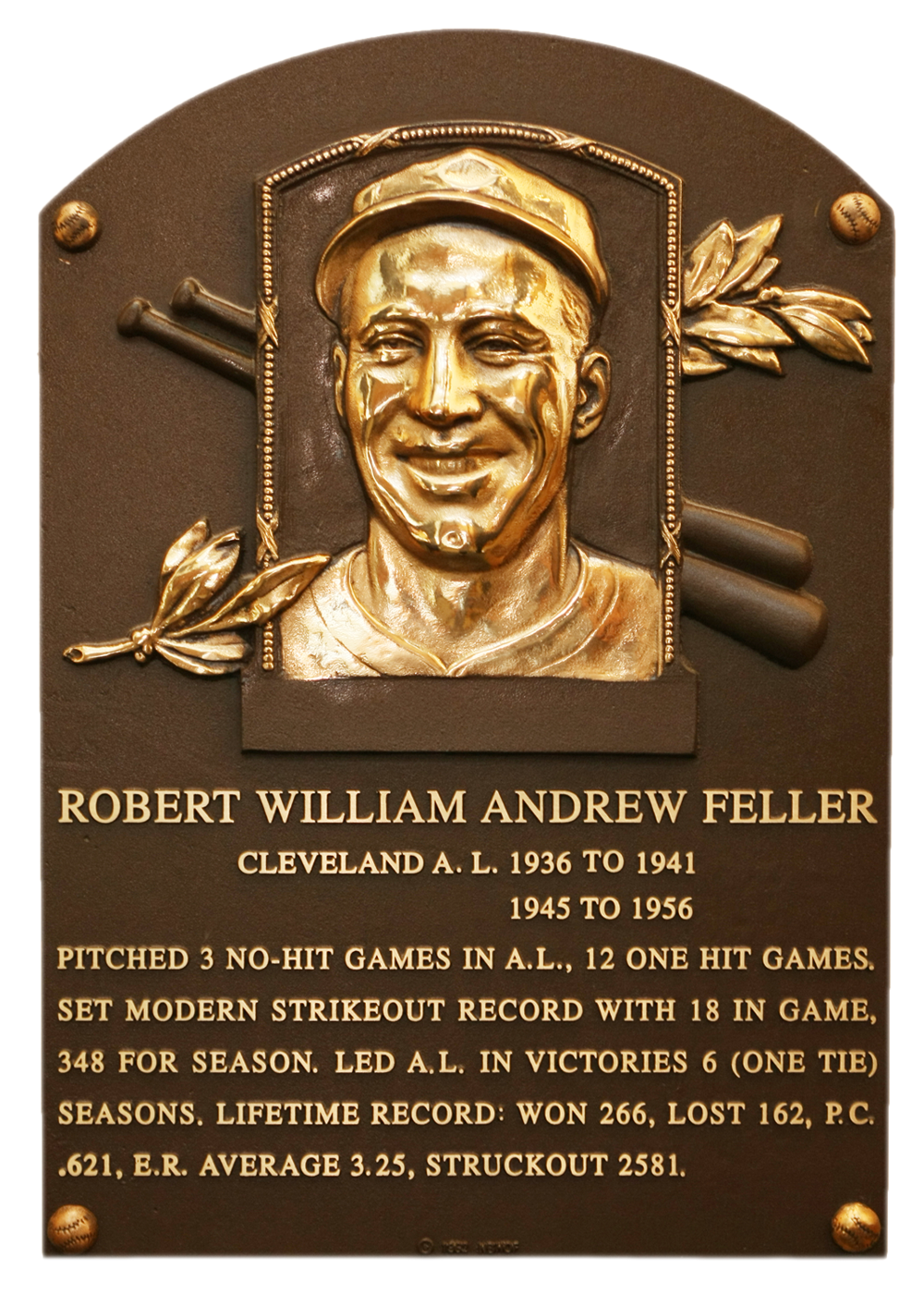

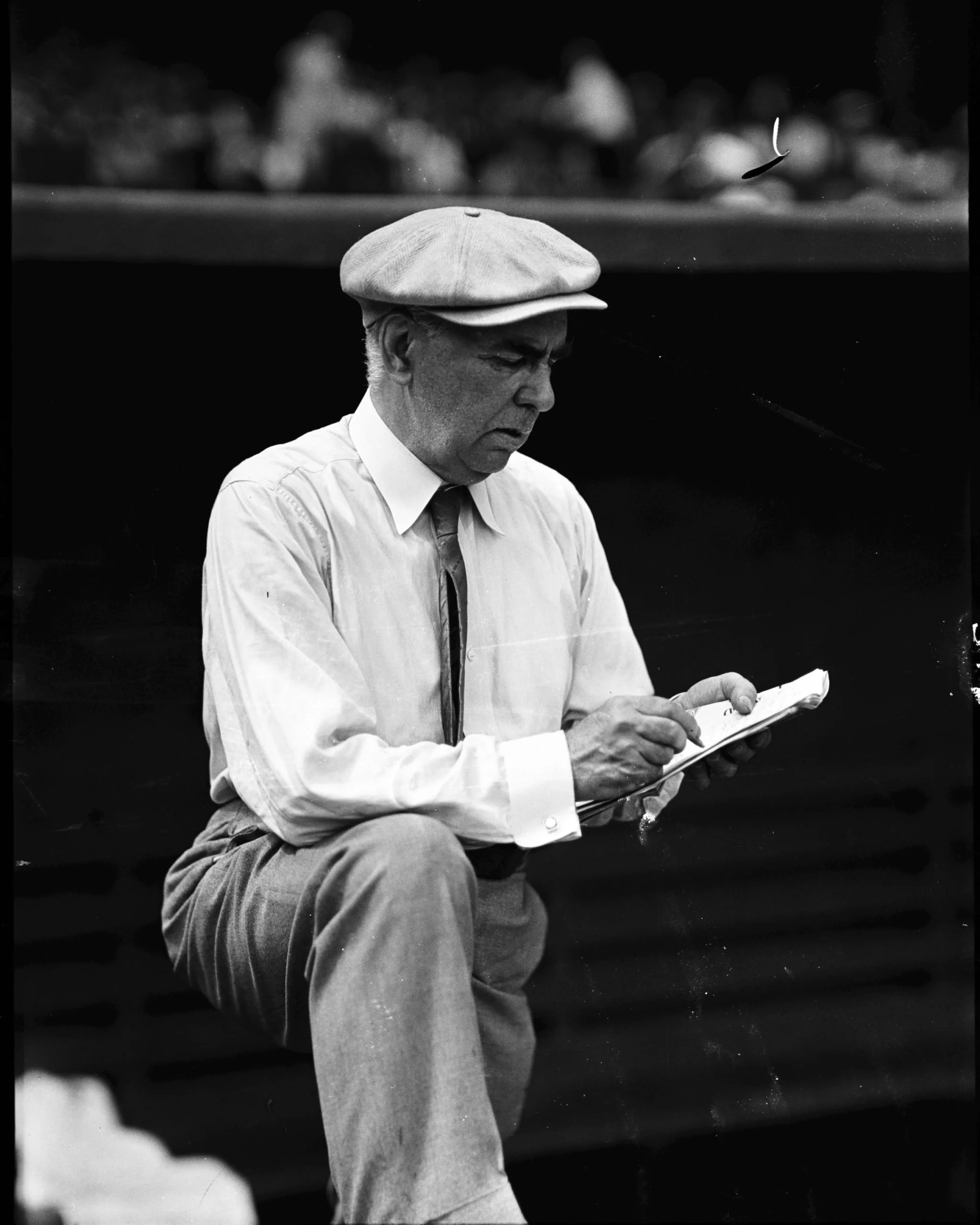

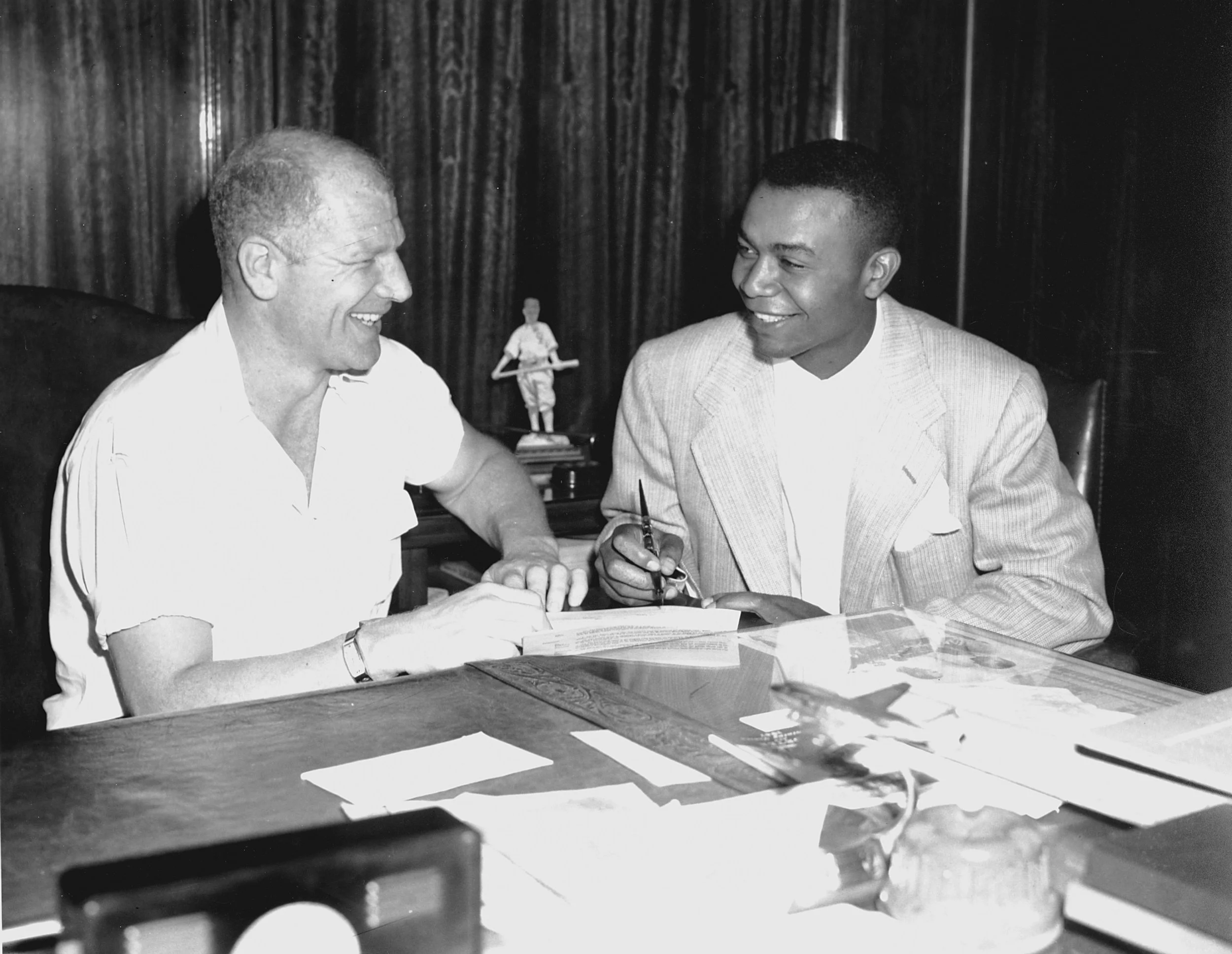

Here, Bradley (right) and Cy Slapnicka (left) are seen signing a contract with Bob Feller.

Buckeyes Accident

In the early morning hours of September 7, 1942, one auto of a caravan of three automobiles carrying Cleveland Buckeyes players and other personnel was involved in a fatal car accident. The team was using three cars as their team bus, pictured here, was in the shop for repairs.

Black Business, More Than Baseball

The Negro Leagues were the third largest Black business in America at their peak, and impacted the Black community and economy in so many ways. From employing umpires and front office people, to stadium workers like concessionaires, ticket takers, ushers, and grounds crews. But teams also traveled, so oftentimes they employed drivers, and when they were in a city away from home, they also patronized Black owned hotels and ate at Black owned restaurants.

The Majestic Hotel

Opened in 1902 as a five-story, 250-room residential hotel known as the Majestic Apartments, the Majestic Hotel emerged after the Great Migration as Cleveland's primary African-American hotel, a role it played until integration eased the need for hotels catering primarily to a black clientele. The imposing brick structure on the corner of East 55th Street and Central Avenue in the heart of the city's Cedar-Central neighborhood provided African Americans with a quality place to stay on a visit or to call home.

Street’s Hotel

The Street’s Hotel was listed in the “Negro Travelers’ Green Book,” a guidebook published annually for African-Americans traveling through America during the era of Jim Crow laws. This guide indicated places that were relatively friendly to African Americans.

It was located on 18th St at Paseo and had 60 guest rooms, each with private bath and telephone service. Conveniently located on the first floor was a haberdasher, a Tailor, a Post Office, and the famous Blue Room Cocktail Lounge and Restaurant.

The Negro Motorist Green Book

An annual guidebook for African-American road trippers founded and published by New York City mailman Victor Hugo Green from 1936 to 1967.

From a New York-focused first edition published in 1936, Green expanded the work to cover much of North America. The Green Book became "the bible of black travel" during the era of Jim Crow laws, when open and often legally prescribed discrimination against African Americans and other non-whites was widespread.

Quincy Gilmore

Quincy J. Gilmore was the secretary of the Kansas City Monarchs from 1922 through 1926, and then again from 1929 through 1939. His brief hiatus was spent acting as the secretary and treasurer of the entire Negro National League. At times, Gilmore also acted as the advance scout for the Monarchs, traveling ahead of the team to make sure their upcoming road trips went smoothly.

In 1929, Gilmore formed the Texas-Oklahoma-Louisiana League and served as the League’s President.

In 1938, Gilmore proposed a plan to nationally organize all the black semipro and independent teams in the United States into a series of regional leagues. The goal of these regional leagues would be to “feed” the Negro American League and Negro National League with ballplayers. Gilmore felt his plan would revitalize Negro League baseball. The press titled the proposed endeavor the “Rube Foster League.” The plan never materialized.

Larry’s Advocacy

Larry’s advocacy led to landmark achievements, including securing retroactive Major League Baseball pensions for over 90 Negro League veterans in 1997 and enrolling approximately 150 former players in Major League Baseball Properties’ royalty program. These initiatives resulted in $143,248 awarded to surviving Negro League players.

White Baseball Writers

We know the names of white baseball writers like Ring Lardner (seen here), Grantland Rice, Hugh Fullerton, Damon Runyon, and Fred Lieb…

White Baseball Photographers

… and we know the names of white baseball photographers like Charles Conlon (seen here), Louis Van Oeyen, Carl J. Horner, Francis Burke, George Burke, and George Brace.

But the names of the journalists and photographers who covered Black baseball in America aren't as well known, if they're known at all.

Wendell Smith

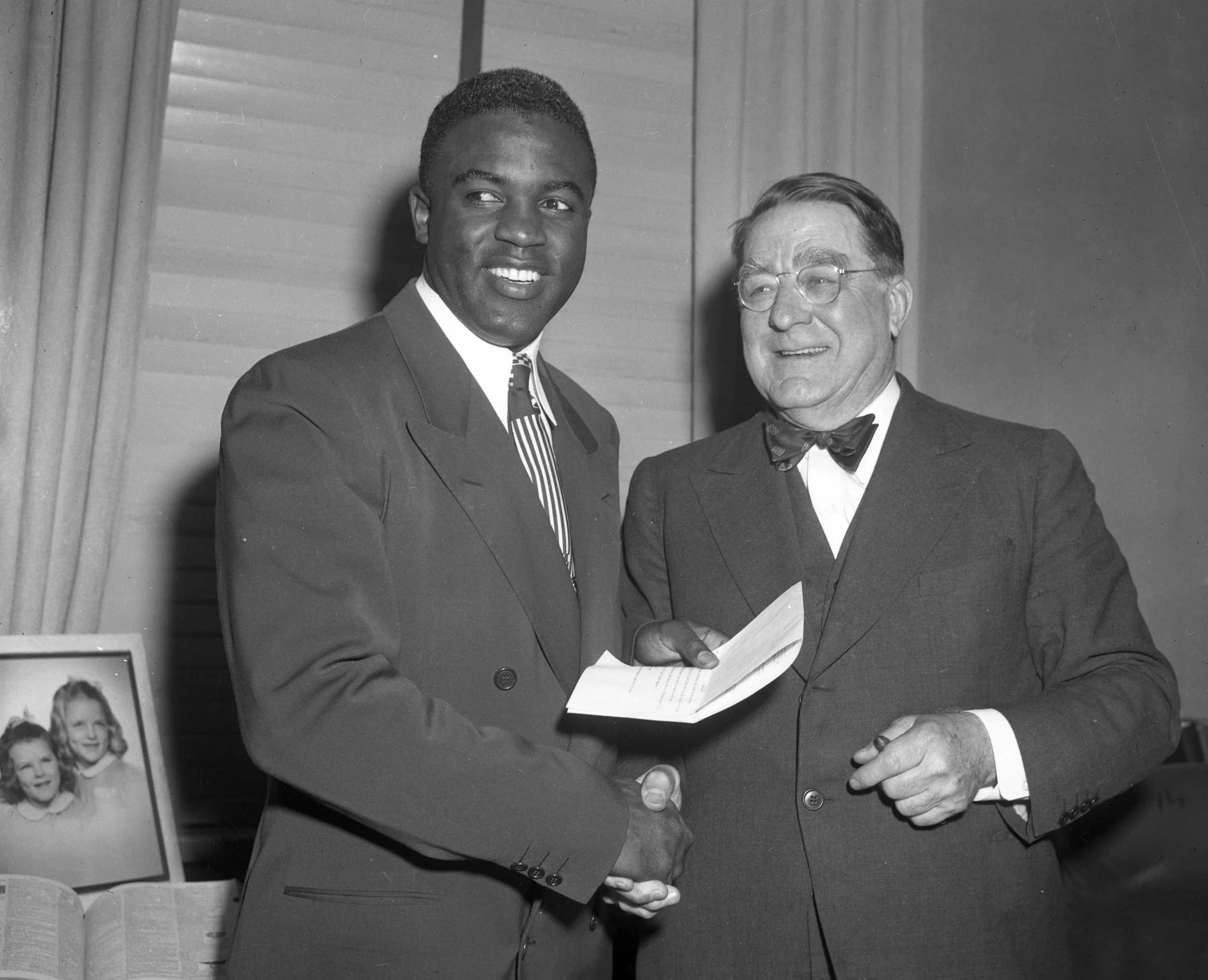

Jackie Robinson had a stellar 1945 season with the Kansas City Monarchs of the Negro leagues but was virtually unknown to most of America. That fall, he picked up a pen to write a letter to the sportswriter Wendell Smith, seen here with Robinson.

“I want to thank you and the paper for all you have done and are doing on my behalf,” Robinson wrote, referring to The Pittsburgh Courier, a prominent Black newspaper. “As you know, I am not worried about what the white press or people think, as long as I continue to get the best wishes of my people.”

The letter was written eight days after Branch Rickey, the president of the Brooklyn Dodgers, announced that he had signed Robinson for the team’s farm club in Montreal, and a year and a half before Robinson broke Major League Baseball’s color line. Decades later, the film “42” illuminated Smith’s vital role in Robinson’s story.

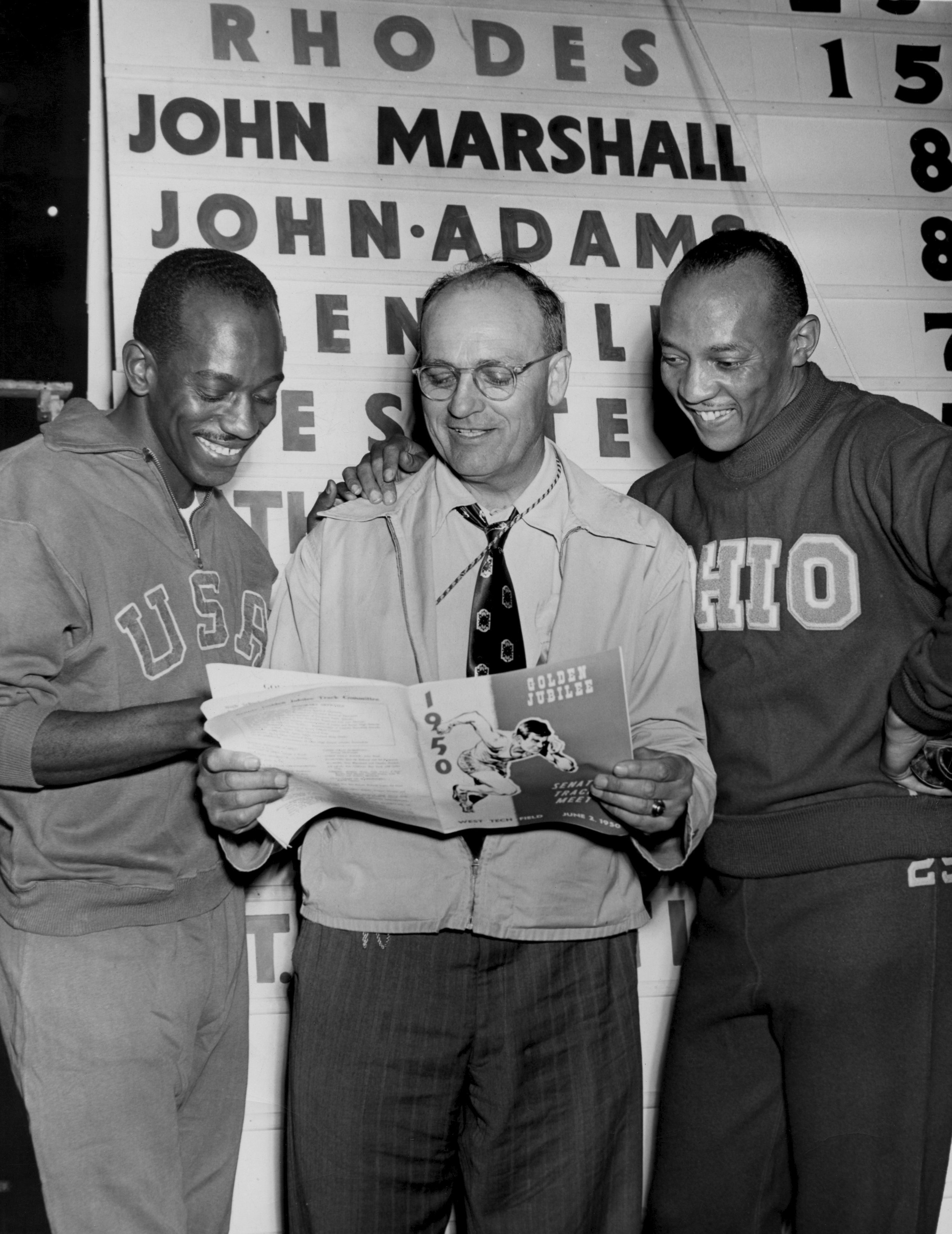

Harrison Dillard

William Harrison "Bones" Dillard (seen here, left, with Jesse Owens, right) was a track and field athlete from Cleveland. Dillard worked for the Cleveland Indians franchise in scouting and public relations capacities, and hosted a radio talk show on Cleveland's WERE. He also worked for the Cleveland City School District for many years as its business manager.

At the 1948 Summer Olympics in London, Dillard reached the final of the 100 meter sprint, which seemed to end in a dead heat between Dillard and another American, Barney Ewell. The finish photo showed Dillard had won, equaling the World record as well. This was the first use of a photo finish at an Olympic Games. As a member of the 4 × 100 meter relay team, he won another gold medal.

Four years later, at the 1952 Summer Olympics in Helsinki, Dillard won gold in the 110 meter hurdles event. Another 4 × 100 meter relay victory yielded Dillard's fourth Olympic title.

He is the only male in the history of the Olympic Games to win gold in both the 100 meter (sprints) and the 110 meter hurdles, making him the “World’s Fastest Man” in 1948 and the “World’s Fastest Hurdler” in 1952.

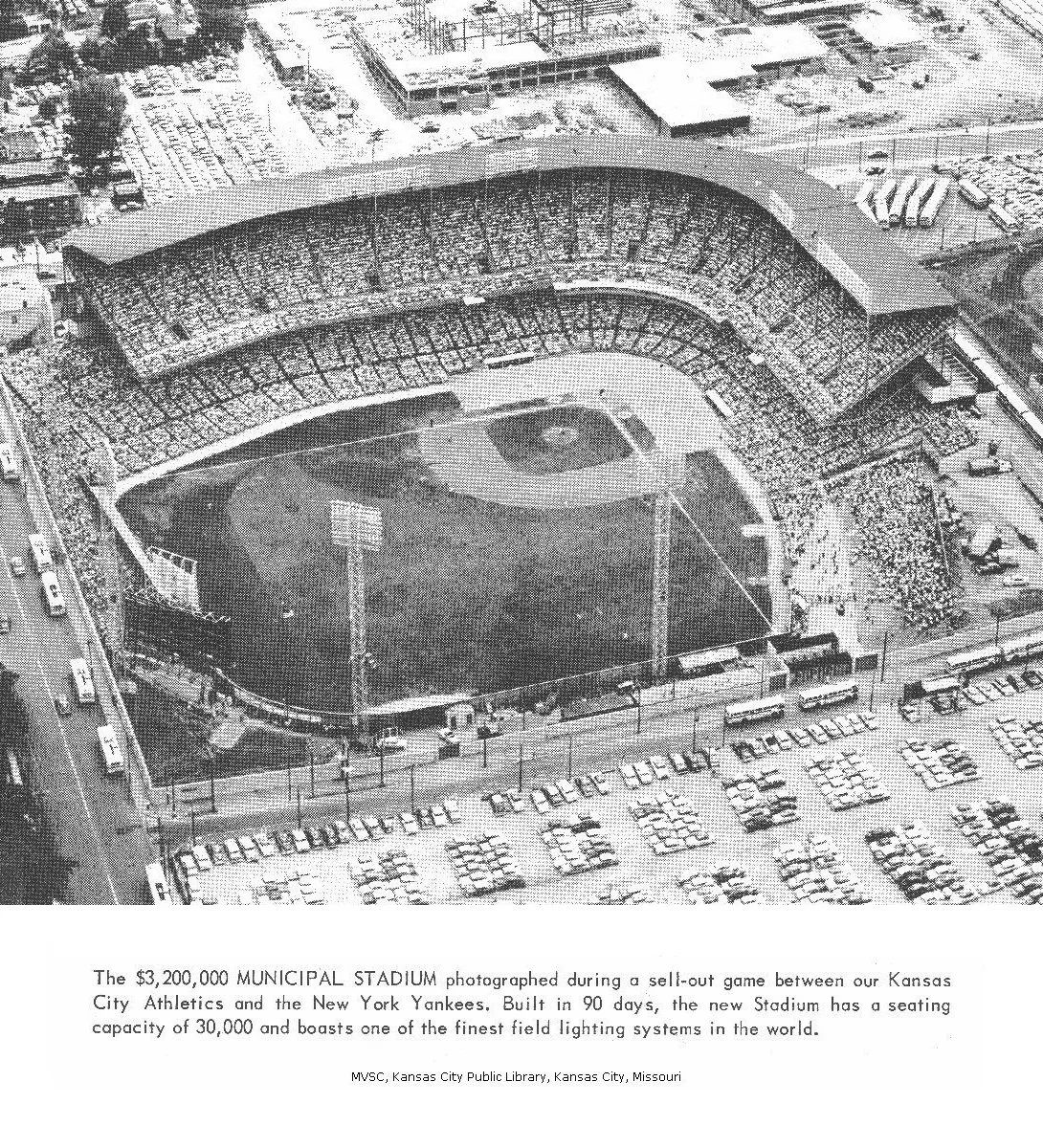

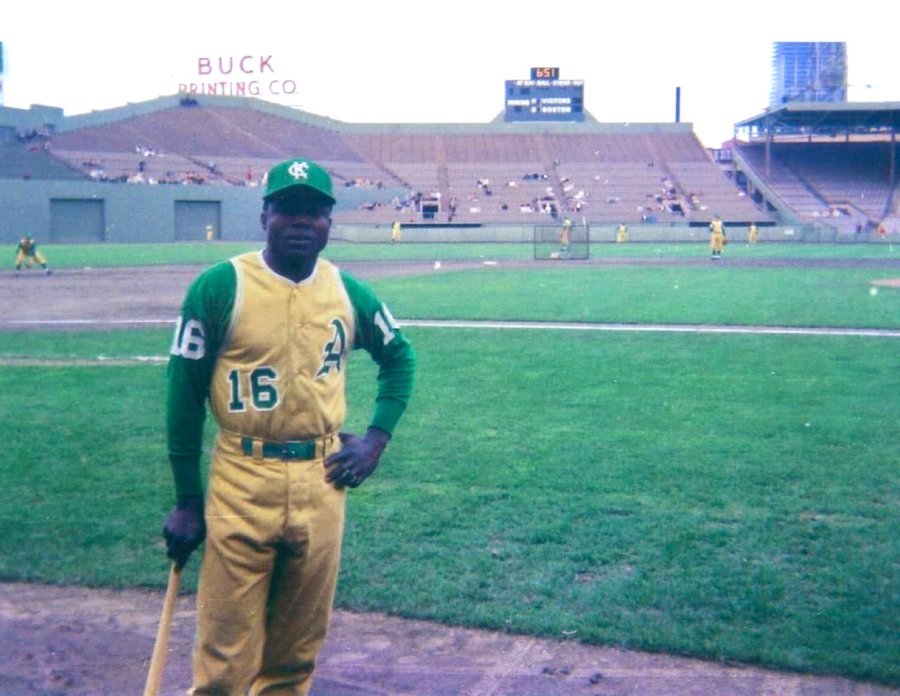

Kansas City’s Municipal Stadium

Larry grew up close to Kansas City’s Municipal Stadium and went to lots of A’s games when the team called KC home.

He asked his family where all of the Black ballplayers were, and that’s when they told him for the first time about Negro League stars like Satchel Paige and Cool Papa Bell. Larry learned that Buck O’Neil, Connie Johnson, and Herman “Doc” Horn all lived nearby, so he started to visit them at their homes where they would tell him stories about the Negro Leagues.

Ed Charles

Ed Charles played for the Kansas City Athletics from 1962–1967 and for the New York Mets from 1967–1969.

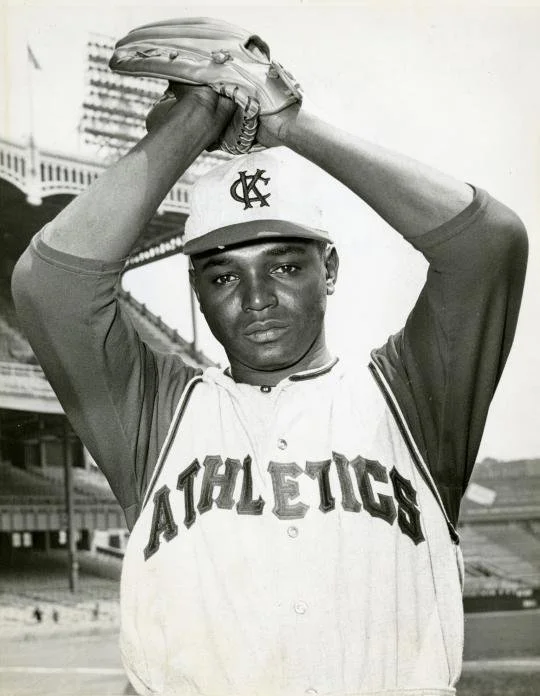

John Wyatt

A former Negro Leagues standout, John Wyatt pitched for nine seasons in the big leagues despite not making it to the majors until he was 26. But with a repertoire of several pitches – some that allegedly included slippery substances – Wyatt made his mark on the 1960s as one of the game’s most durable relievers.

Roommates

More often than not, integrated teams would have an even number of Black players to optimize hotel space. Black and white players couldn’t share a room, so instead of leaving a Black player with a room to himself if the team had three or five minorities on the team, they would structure their rosters to ensure an even split.

Johnny Wright was a right-handed pitcher with an outstanding curveball. He played for the Newark Elites, the Indianapolis Clowns, the Atlanta Black Crackers, the Pittsburgh Crawfords, and the Homestead Grays of the Negro Leagues.

In 1943, Wright won 25 regular-season games for the Grays and added two shutouts in the Negro League World Series. Branch Rickey chose Wright to room with Jackie Robinson as teammates in Montreal.

Different Sport, Same Story

In Jim Brown’s autobiography Out Of Bounds, he confirms that the NFL employed the same even-number strategy as Major League Baseball when it came to rostering Black players on teams.

Buy Out Of Bounds by Jim Brown and Steve Delsohn HERE

Larry Doby

Stephanie was enamored with the story of the 1948 Cleveland Indians, particularly the trials and tribulations of Larry Doby and Satchel Paige. When she wanted to learn more about them, and started to follow their careers backwards to the Negro Leagues, her eyes were opened to an entire new world of characters and stories.

Stephanie’s Favorite Players

Growing up, Stephanie’s favorite players included Joe Carter and Barry Bonds. As she learned more about the Negro Leagues, and the fact that Black baseball leagues had to exist in the first place, she began to wonder what it would have been like had she never had a chance to watch the great Black ballplayers of her childhood play in Major League Baseball.

That made Stephanie think about all of the players who did miss that opportunity, and missed out on a larger group of fans knowing about them and seeing their talents.

Louis Jones

In January of 1947, Bill Veeck hired Bill Killefer, a former player and longtime coach, to scout the Negro Leagues. Around that same time, he hired a Black man named Louis Jones -- a promoter and the first husband of singer and actress Lena Horne -- as the team’s assistant director of public relations. Jones, therefore, became the first Black executive in MLB, tasked with engaging with the city’s Black civic leaders and neighborhoods in preparation for the desegregation of the team.

In Doby’s book Pride Against Prejudice, he mentions arriving in Cleveland on July 4, 1947, and having Jones, the newly-hired African-American assistant public relations director, assigned to be his roomie. Satchel Paige became Doby’s bunk mate the next season.

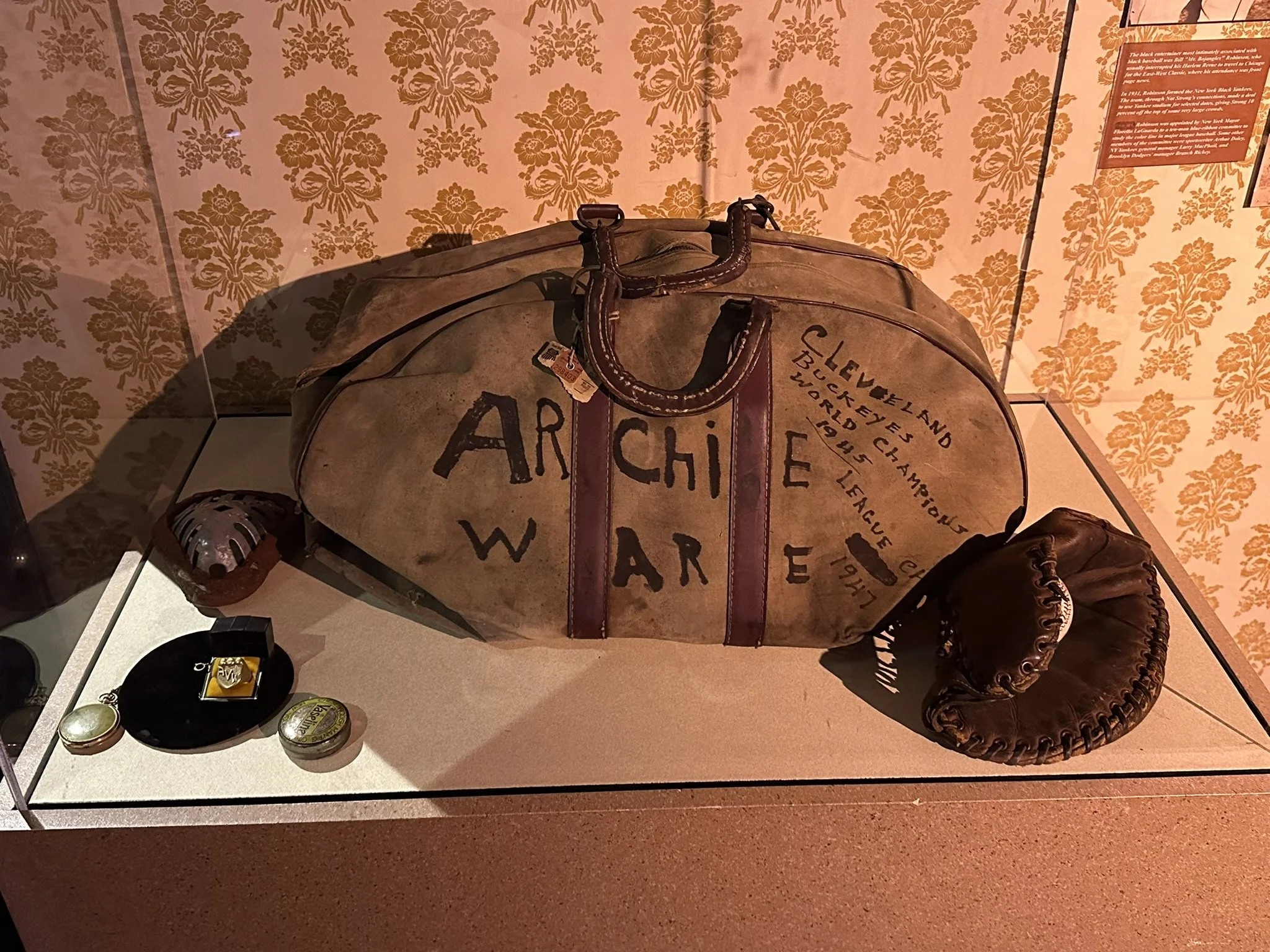

Negro League Artifacts

Larry acquired rare artifacts from the families of Satchel Paige, Oscar Charleston, Josh Gibson, Archie Ware, Chet Brewer and others for the Negro League Baseball Museum’s static exhibit and archives.

Archie Ware

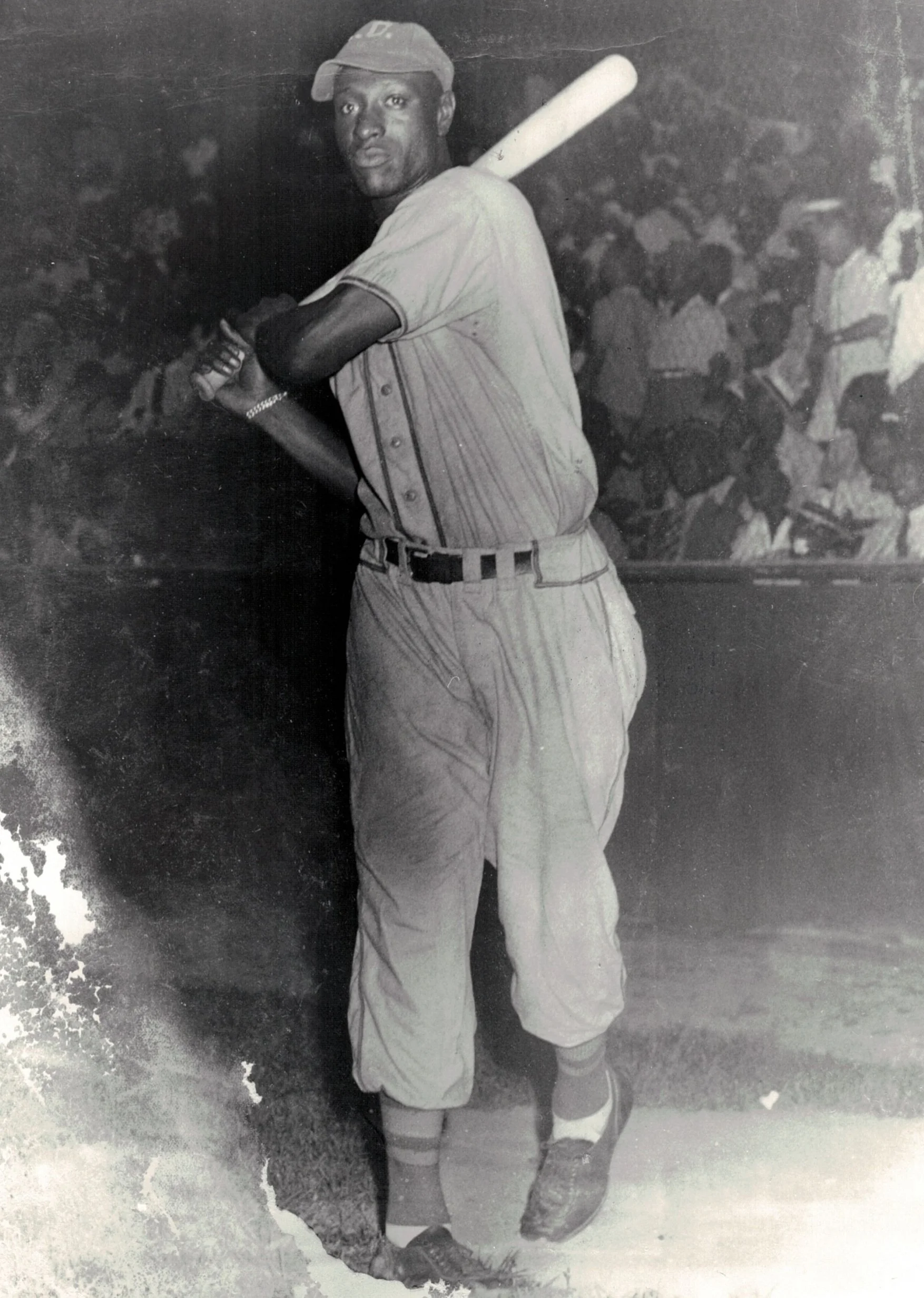

Archie Ware played first base in the Negro Leagues between 1942 and 1952.

In between, Ware also played winter ball in Venezuela with the Navegantes del Magallanes club in the 1947-48 season. He also played for the Spur Cola Colonites of Panama in 1950-51, playing for Spur Cola in the 1951 Caribbean Series.

“Major” Leagues

In December 2020, Larry’s comprehensive compilation of Negro League records from 1920 through 1948 was officially recognized by Major League Baseball, rewriting the historical record books to include Black players, Black teams, and their statistics. But only for certain years, and sometimes only certain games from those “accepted” years, and only if those leagues met certain criteria.

The seven different Major Negro Baseball Leagues whose records have been absorbed into the official Major League Baseball record books are listed here.

Turkey Stearnes

Negro Leagues legend Satchel Paige called Turkey Stearnes “one of the greatest hitters we ever had. He was as good as Josh [Gibson]. He was as good as anybody who ever played ball”.

Stearnes was widely recognized as one of the game’s all-time great players during his career. Negro Leaguer Jim Canada, who played against Stearnes said: “He hit the ball nine miles. He was a show, people would go to see him play.”

Stearnes could win games with both his arms and his legs. A swift center fielder who excelled on the bases, Stearnes led the Negro National League in batting average twice and is credited with 129 stolen bases.

"That man could hit the ball as far as anybody," Cool Papa Bell said. "And he was one of our best all around players. He could field, he could hit, he could run. He had plenty of power."

Pete Hill

Playing most of his career in the pre-Negro Leagues era, Pete Hill emerged from the backwoods of Culpeper County, Virginia, to become one of the most feared line-drive hitters in the game. His baseball years run roughly from 1889 to the mid-1920s and involve some of the pioneer programs of African-American baseball.

Hill was considered to be a premier center fielder with a rocket arm and excellent glove. His talents also extended to the batter’s box, where he was a consistent line-drive hitter with outstanding speed on the base paths.

Baseball historian Jim Riley has said that if an all-star outfield was created from the pre-1920 era, it would include Ty Cobb, Tris Speaker and Pete Hill. The Chicago Defender supports this, as noted from an article in 1910: Hill can “do anything a white player can do. He can hit, run, throw and is what is termed a wise, heady ballplayer.”

Napoleon Lajoie

“Lajoie was one of the most rugged hitters I ever faced. He’d take your leg off with a line drive, turn the third baseman around like a swinging door, and powder the hand of the left fielder.” – Cy Young

Napoleon Lajoie, hitter extraordinaire, sublime fielder, manager and executive, has been described as “the first superstar in American League history.” And indeed, to concentrate on his hitting or his fielding is to miss his all-around talent as a player.

Lajoie combined graceful, effortless fielding with powerful, fearsome hitting to become one of the greatest all-around players of the Deadball Era, and one of the best second basemen of all time.

At 6’1″ and 200 pounds, Lajoie possessed an unusually large physique for his time, yet when manning the keystone sack he was wonderfully quick on his feet, threw like chain lightning, and went over the ground like a deer.

Tris Speaker

“At the crack of the bat he'd be off with his back to the infield, and then he'd turn and glance over his shoulder at the last minute and catch the ball so easy it looked like there was nothing to it, nothing at all." – Smoky Joe Wood

Legendary for his short outfield play, Tris Speaker led the American League in putouts seven times and in double plays six times in a 22-year career with Boston, Cleveland, Washington, and Philadelphia. Speaker’s career totals in both categories are still major-league records at his position.

No slouch at the plate, Speaker had a lifetime batting average of .345, sixth on the all-time list, and no one has surpassed his career mark of 792 doubles.

“Minnie” Miñoso

Orestes “Minnie” Miñoso was traded from the Cleveland Indians to the Chicago White Sox instead of Harry Simpson. But why did Cleveland feel the need to trade either player?

Because many teams, at the time, felt like having “too many” Black players on their team might alienate their white fans. Many clubs had these self-imposed limits, though you could argue that the only thing they were limiting was their team’s potential.

Josh Gibson

Only 60-80 games per season were actually considered official Negro League games, so the statistics don't seem impressive always.

But teams would play upwards of 100 barnstorming games in addition to actual regular season Negro League games.

Because of those barnstorming games, Josh Gibson’s HOF plaque states he hit “almost 800 home runs,” but since only a fraction of those home runs came in officially accepted Negro League/“Major” League games, he is now officially credited with just 166 career home runs.

No Need To Embellish

The real stories are incredible enough.

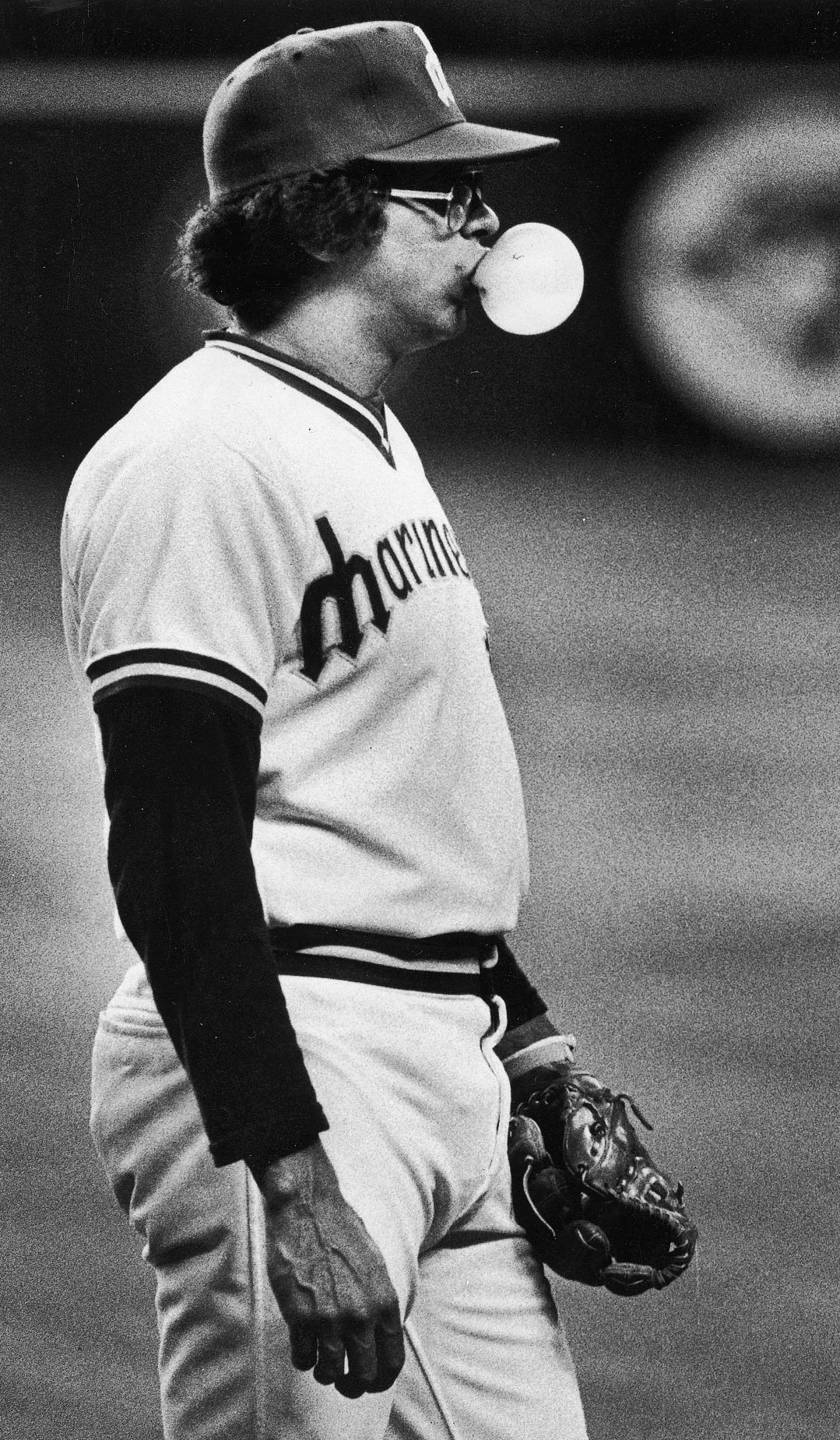

The Mendoza Line

The Mendoza Line is baseball jargon for a .200 batting average, the supposed threshold for offensive futility in Major League Baseball.

It derives from light-hitting shortstop Mario Mendoza, who failed to reach .200 five times in his nine big league seasons. When a position player's batting average falls below .200, the player is said to be "below the Mendoza Line".

Black Baseball’s National Showcase

When the best Black baseball players assembled for the annual East-West All-Star games, which for a generation paralleled the white All-Star games, the concentration of talent on the field was second to none. This scholarly work brings together the painstakingly assembled history of those games, reconstructed play-by-plays, and accurate statistical records.

Larry recaptures the vigor of the Black communities' united attention to the event, describes the players whose talents brought them to this pinnacle of achievement, and discusses the less salubrious but still important stratagem of promoters, gamblers, and petty tyrants who cast an occasional shadow on the sunlit fields of Chicago's Comiskey Park.

Buy a copy of this amazing book HERE.

East-West All-Star Game

In 1933, Arch Ward of the Chicago Tribune pitched the idea of having an All-Star Game as part of the festivities surrounding the 1933 World’s Fair in Chicago. That same summer, the Negro Leagues decided to try it for themselves, also in Chicago.

The Negro League version wasn’t just a baseball game, though. It was the place to be, and the place to be seen. Everyone in Black popular culture wanted to be at these games, and many of them were regular attendees.

People from all areas of fame: Duke Ellington, Lena Horne and her father, Teddy Horne, Lionel Hampton, Count Basie, Louis Armstrong, Joe Louis… the list goes on and on.

1939 East-West Game

Of the 32,000 people in the stands at the East-West game at Comiskey Park in Chicago, less than 1,500 were White baseball fans paying their way.

Fay Young of the Chicago Defender offered his own postgame commentary on the bigger picture, lamenting the attendance and considering the causes for such poor numbers:

“In other words, the success of the game was made by Negro newspapers and the daily press. Even as liberal as [the White press] were here, it didn’t put people in the gate.”

Black Baseball Teams In Cleveland

Cleveland had more official Negro League teams than any other city, but it's because they all failed.

Graphic courtesy of the research by Phil Dixon

Cleveland Buckeyes

The Buckeyes were the first Black baseball team to really succeed in Cleveland. They went to the 1945 and 1947 Negro League World Series, and won the 1945 Series against the Homestead Grays.

Homestead Grays

The 1945 Grays had five future Hall of Famers on their team: Josh Gibson, Cool Papa Bell, Buck Leonard, Ray Brown, and Jud Wilson.

How Did The Buckeyes Win?

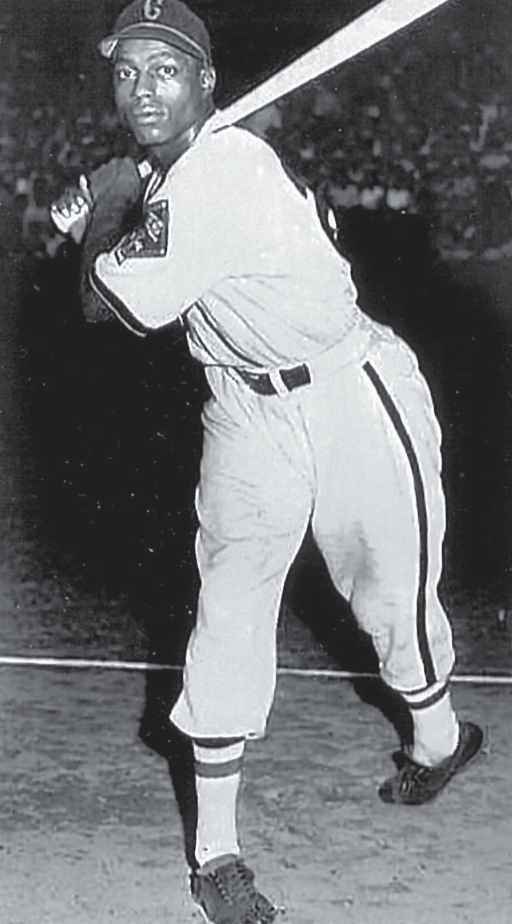

With great play from Parnell Woods, Sam Jethroe, and Eugene Bremer (seen here), who we have mentioned already. But also with the help of other players, like Johnnie Cowan and Willie Jefferson.

The Buckeyes pitching staff had the series of their lives, holding the offensive juggernaut on the other side of the diamond in check. Not only did the Buckeyes win the series, they swept the Grays, who were heavily favored.

Multi-talented

Many Negro League players were two-way stars, who could pitch and hit, as well as play other positions in the field. Not all of them were as good at playing both sides of the ball as Martín Dihigo, but many could more than adequately fill in at multiple positions on a moment’s notice.

When you allow the best players from all over the world to play in your league, regardless of skin color, the level of talent and competition is going to be fierce. And that’s exactly what it was in the Negro Leagues.

Rube Foster

Although Andrew "Rube" Foster (1879-1930) stands among the best African American pitchers of the 1900s, this baseball pioneer made his name as the founder and president of the Negro National League, the first all-black league to survive a full season. In addition to founding this groundbreaking black-owned and -operated business, the eventual Hall of Famer also founded and managed the Chicago American Giants, one of the most successful black baseball teams of the pre-integration era.

Larry’s definitive biography combines period editorials and correspondence with insightful narrative to provide a comprehensive portrait of Foster. From the unstructured early days of black baseball, when Foster gained glory as a hard-throwing pitcher, through his struggles to establish the NNL and the Giants, to his tragic death from complications of syphilis, this work pays overdue tribute to an authentic American baseball icon.

Buy a copy of the book HERE.

1914 Chicago American Giants

Front row, from left: Billy “Little Corporal” Francis (third base), Richard “Dick” Whitworth (pitcher), Joseph Preston “Pete” Hill (shortstop), Andrew “Rube” Foster (owner-manager), Bruce Petway (catcher), James “Pete” Booker (catcher) and an unidentified person.

Back row, from left: Bill Gatewood (pitcher); Jesse Barber, also Barbour (first base); Leroy Grant (first base); John Henry “Pop” Lloyd (shortstop); and Robert “Jude” Gans (outfield).

The New Negro by Alain Locke

The New Negro: An Interpretation is an anthology of fiction, poetry, and essays on African and African-American art and literature edited by Alain Locke, and first published in 1925.

Locke lived in Washington, DC, and taught at Howard University during the Harlem Renaissance.

As a collection of the creative efforts coming out of the burgeoning New Negro Movement or Harlem Renaissance, the book is considered by literary scholars and critics to be the definitive text of the movement.

Part 1 of The New Negro: An Interpretation, titled "The Negro Renaissance," includes Locke's title essay "The New Negro," as well as nonfiction articles, poetry, and fiction by writers including Countee Cullen, Langston Hughes, Zora Neale Hurston, Claude McKay, Jean Toomer and Eric Walrond.

You can read the entirety of the text HERE.

The “Red Summer” of 1919

On July 27, 1919, thousands of Chicagoans sought relief from the brutal heat on the shores of Lake Michigan. Among them was Eugene Williams, a 17-year-old African American.

When he and his friends inadvertently drifted across an invisible line that divided the waters by race, a group of whites, insulted by such an act, began throwing stones at them, one of which struck Williams, causing him to drown.

In the racial powder keg that was Chicago, his murder was the spark that ignited it during what became the Red Summer of 1919.

New York Rens

The New York Rens were the first Black-owned, all-Black, fully professional basketball team in history, formed in Harlem in October 1923. That year, basketball manager Robert “Bob” Douglas made a deal with Harlem real estate developer William Roach, the owner of the Renaissance Casino, a newly opened ballroom.

Douglas asked Roach if the Spartans could play their home games at his ballroom in exchange for changing the name of the team to the “New York Renaissance” to promote the dance hall far and wide. Douglas, now armed with a permanent home court, introduced full-season player contracts to lock in his players. The “Rens” attracted the best African American talent in basketball.

“Double V Campaign”

In 1942 the African-American weekly Pittsburgh Courier started what they referred to as the “Double V Campaign”—black Americans not only had to fight for victory in the war, but also fight for equality on the home front. Baseball was a popular target; one of the arguments for the integration of baseball was that it would lead to desegregation in other areas of society. In fact, the military was desegregated a year after Robinson broke the color barrier.

Sam Lacy

Samuel Harold Lacy was an African-American and Native American sportswriter, reporter, columnist, editor, and television/radio commentator who worked in the sports journalism field for parts of nine decades.

Credited as a persuasive figure in the movement to racially integrate sports, Lacy in 1948 became one of the first black members of the Baseball Writers' Association of America. In 1997, he received the J. G. Taylor Spink Award for outstanding baseball writing from the BBWAA.

Eric “Ric” Roberts

In April 1945, the major leagues announced the name of their new commissioner: Senator A.B. “Happy” Chandler of Kentucky. ''We went right down to see him the morning the story broke,'' said Eric (Ric) Roberts, a long time writer for The Pittsburgh Courier.

''Chandler came out immediately, shaking our hands, and said, 'I'm for the Four Freedoms. If a black boy can make it on Okinawa and Guadalcanal, hell, he can make it in baseball.' And he told us, 'Once I tell you something, brother, I never change. You can count on me.' I always thought that was a pretty stout thing for a Southerner to say.''

As Tom Conmy writes, “Ric Roberts was adept at cartoons and illustrations for all sports, but for baseball, football and boxing especially. Being a respected sports columnist since the 1930’s, he eventually became the sport editor for the Courier, as well. As with many of his contemporaries, he toiled in semi-obscurity for decades, but his work has always deserved a greater audience.”

Frank A. Young

Frank Albert Young (aka “Fay,” for his initials) was a journalist who wrote for many years for The Chicago Defender. Young was widely regarded as the "dean of Negro sportswriters."

He helped organize the Negro National League in 1920, and served as statistician until the league disbanded in 1933. He also served as an official for the Illinois Athletic Commission, serving as a timekeeper at prizefights; he was also a former secretary of the Negro American League.

The Reserve Clause

The reserve clause was part of a player contract which stated that the rights to players were retained by the team upon the contract's expiration. Players under these contracts were not free to enter into another contract with another team. Once signed to a contract, players could, at the team's discretion, be reassigned, traded, sold, or released.

The only negotiating leverage of most players was to hold out at contract time and to refuse to play unless their conditions were met. Players were bound to negotiate a new contract to play another year for the same team or to ask to be released or traded. They had no freedom to change teams unless they were given an unconditional release.

Integration Killed A Lot of Black Businesses

As written by Japheth Knopp, “The decline and end of the Negro Leagues may provide insights about the changing realities for urban African-Americans in the years after World War II.

Shifting political and economic opportunities, and the limits of those opportunities, have had a profound effect on American society, especially for African-Americans, over the course of the last eight decades. The early stages of integration in American society brought with it new hopes for marginalized minority groups; however, it also posed new challenges.

Traditionally black-owned enterprises – among them the Negro Leagues – now faced increased competition for black workers and revenue and had difficulties maintaining sustainable businesses, which resulted in the failure of most medium and large-scale black firms during the mid-twentieth century.”

Mays’ Lost Time

Willie Mays won the National League Rookie of the Year award in 1951, but then immediately missed 120 games in the 1952 season, and all 154 games of the 1953 season due to his military service.

When Willie returned for his first season back in 1954, he led the Major Leagues with 10.4 WAR, a .345 batting average, and a .667 slugging percentage, winning the MVP and leading the Giants to a World Series win.

He hit 41 home runs that year, and then 51 the following year in 1955. Even a conservative estimate gives him another 60 home runs from those missed games in 1952 and 1953, and somewhere in the neighborhood of an additional 310 hits.

That takes his career home run total to 720, instead of 660, giving him the most all time, at the time of his retirement. Only Henry Aaron and Barry Bonds have since eclipsed that total, meaning Willie would now be 3rd all-time in Home Runs, instead of 6th.

And Lost Statistics

Another 310 hits gives Willie 3,603 for his career, which would have put him 3rd all-time at the time of his retirement, behind only Ty Cobb and Stan Musial. Only Henry Aaron and Pete Rose have since eclipsed that total, meaning Willie would now be 5th all-time in hits, instead of 13th.

Another 160 runs bumps him up to 2,228, which puts him at 3rd all time, instead of 7th, just 17 behind Ty Cobb for 2nd place, and 67 behind Rickey Henderson for 1st.

Another 180 Runs Batted In bumps him up to 2,089, which puts him at 4th place all time, instead of 12th, and would make him one of only 6 players with more than 2,000 RBI in his career.

Willie is already one of only 4 players in history with more than 6,000 total bases, but adding another 500 for the time he missed in the military moves his career total up to 6,580 and in to second place all time, behind only Henry Aaron's 6,856.

Only So Much Money To Go Around

Black fans (and newspapers, as well) sometimes had a difficult choice to make, once baseball was integrated: do we go see our Black stars playing in the Major Leagues so we can witness them making history in person, or do we continue to financially support the Negro Leagues by attending those games, even if the best players have been plucked from the league? With limited money to spend on entertainment, and limited time, it was a tough choice for many fans and media outlets.

1940 Kansas City Monarchs

Suffering from an arm injury and generally thought to be done pitching, Satchel Paige joined the Monarchs' B team in 1939. By 1940, he had recovered and was called up to the Monarchs' main squad, where he became their top drawing card.

The Monarchs went 38-13-1 in Negro American League play that year, winning the first half championship and the second half championship to become the undisputed champions of the league.

The team featured six future members of the National Baseball Hall of Fame, including Paige (who was inducted in 1971), Willard “Home Run” Brown (2006), Buck O’Neil (2022), Hilton Smith (2001), Turkey Stearnes (2000), and manager Andy Cooper (2006).

1943-44 Homestead Grays

The Homestead Grays won the Negro National League’s first half championship, its second half championship, and the Negro League World Series in both 1943 and 1944, an absolutely dominating run.

The team featured five future members of the National Baseball Hall of Fame, including Josh Gibson (who was inducted in 1972), Cool Papa Bell (1974), Buck Leonard (1972), Ray Brown (2006), and Jud Wilson (2006).

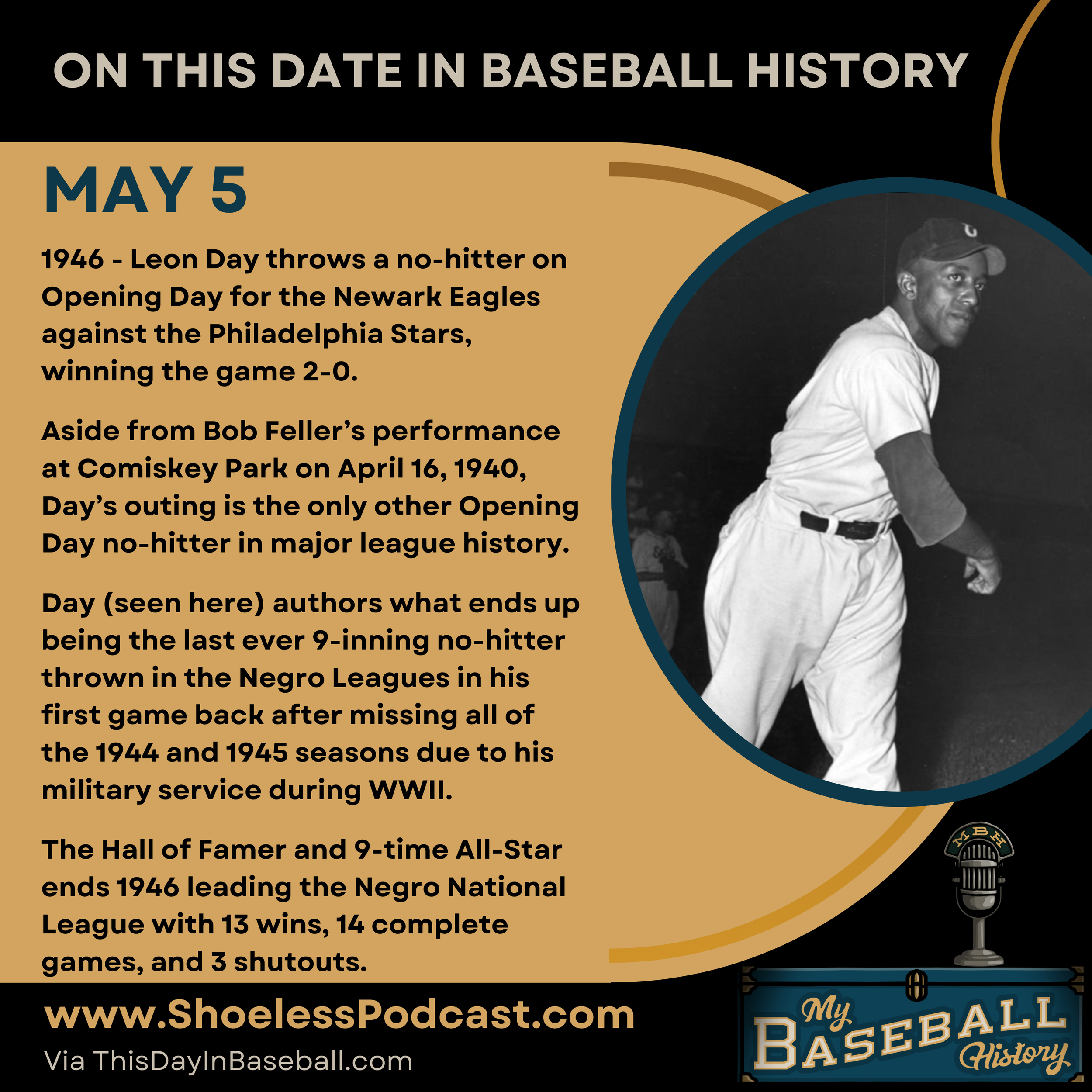

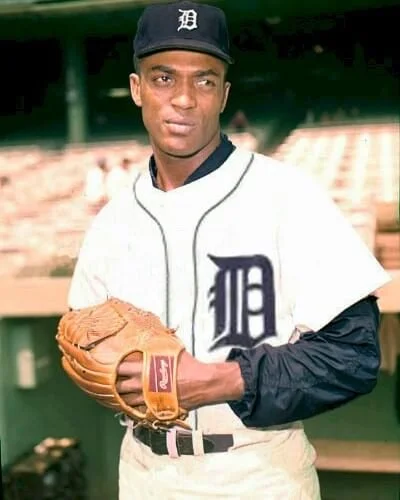

1946 Newark Eagles

The Newark Eagles won the Negro National League’s first half championship, its second half championship, and the Negro League World Series in 1946, finishing the season with a 46-16-2 record in league play.

The team featured four future members of the National Baseball Hall of Fame, including Larry Doby (who was inducted in 1998), Monte Irvin (1973), Leon Day (1995), manager Biz Mackey (2006), and owner Effa Manley (2006).

Leon Day

“People don't know what a great pitcher Leon Day was. He was as good or better than Bob Gibson. He was a better fielder, a better hitter, could run like a deer. When he pitched against Satchel, Satchel didn't have an edge. You thought Don Newcombe could pitch. You should have seen Day! One of the best complete athletes I've ever seen.” – Monte Irvin

When rumors swirled about the Pittsburgh Pirates possibly giving tryouts to Black ballplayers, the Pittsburgh Courier speculated who might be given such tryouts: “Leon Day is the type of hurler the Pirates need… He has all the qualities necessary for the majors. We believe he could do much better than the Pirates’ leading hurler, Rip Sewell.”

Day was inducted into the National Baseball Hall of Fame in 1995.

1947 New York Cubans

The New York Cubans won the Negro League World Series in 1947, defeating the Cleveland Buckeyes (who had just won in 1945) in six games, winning four while having one game called a tie due to rain after six innings. The Cubans finished the season with a 43-18-1 record in Negro National League play.

The team featured Orestes “Minnie” Miñoso (who was inducted into the National Baseball Hall of Fame in 2022), Pat Scantlebury, Ray Noble, player-manager José María Fernández, and Lino Donoso (who was inducted into the Mexican Professional Baseball Hall of Fame in 1988).

Ted Strong

Theodore Reginald Strong, Jr. played in the Negro Leagues from 1936 to 1942 and again from 1946 to 1951 for the Chicago American Giants, Indianapolis Athletics, Kansas City Monarchs, Indianapolis ABCs, and Indianapolis Clowns. Strong's career was interrupted while he served in World War II from 1943 to 1945 as a Seabee in the Marshall Islands.

In his nine seasons playing in the Negro Leagues, he was named an All-Star seven times, and his teams won the pennant five times. Strong won two batting titles, and won the Negro American League’s Triple Crown in 1942, leading the league in home runs, runs batted in, and batting average.

Strong also played basketball for the original Harlem Globetrotters from 1935 to 1942 and from 1946 to 1949, during the baseball off-season. In 1942, he also briefly played for the Chicago Studebaker Flyers of the National Basketball League, along with other Globetrotters, as one of the first Black players in the league.

Oscar Charleston

“Charlie was a tremendous left-handed hitter who could also bunt, steal a hundred bases a year, and cover center field as well as anyone before him or since… he was like Ty Cobb, Babe Ruth, and Tris Speaker rolled into one.” – Buck O’Neil

A powerful hitter who could hit to all fields and bunt, Oscar Charleston was also extremely fast on the base paths and in center field. He played a very shallow center, almost behind second base, and his great speed and instincts helped him outrun many batted balls. He had a powerful arm. Coupled with this great natural ability was an aggressive demeanor and will to win.

From the mid-1920s on, he was a player-manager for several clubs. In 1933, he joined the Pittsburgh Crawfords and would manage the 1935 Crawfords club that many consider the finest Negro League team of all time. He played nine seasons of winter ball in Cuba, amassing statistics quite similar to his big league achievements.

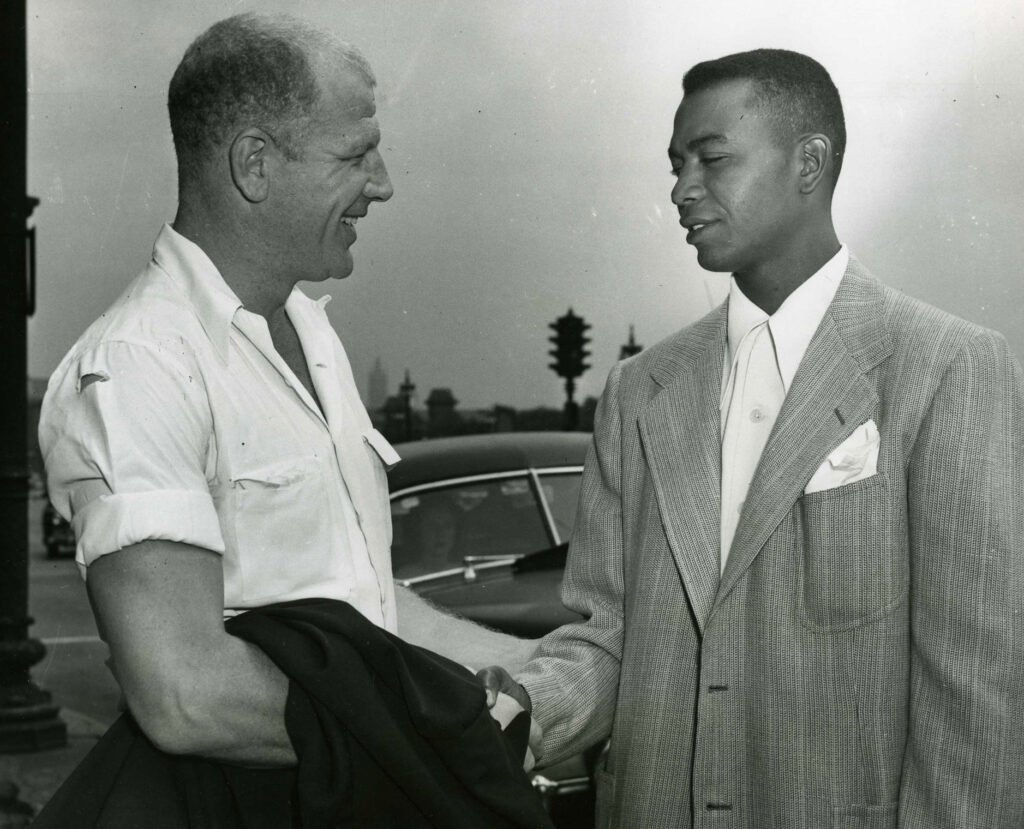

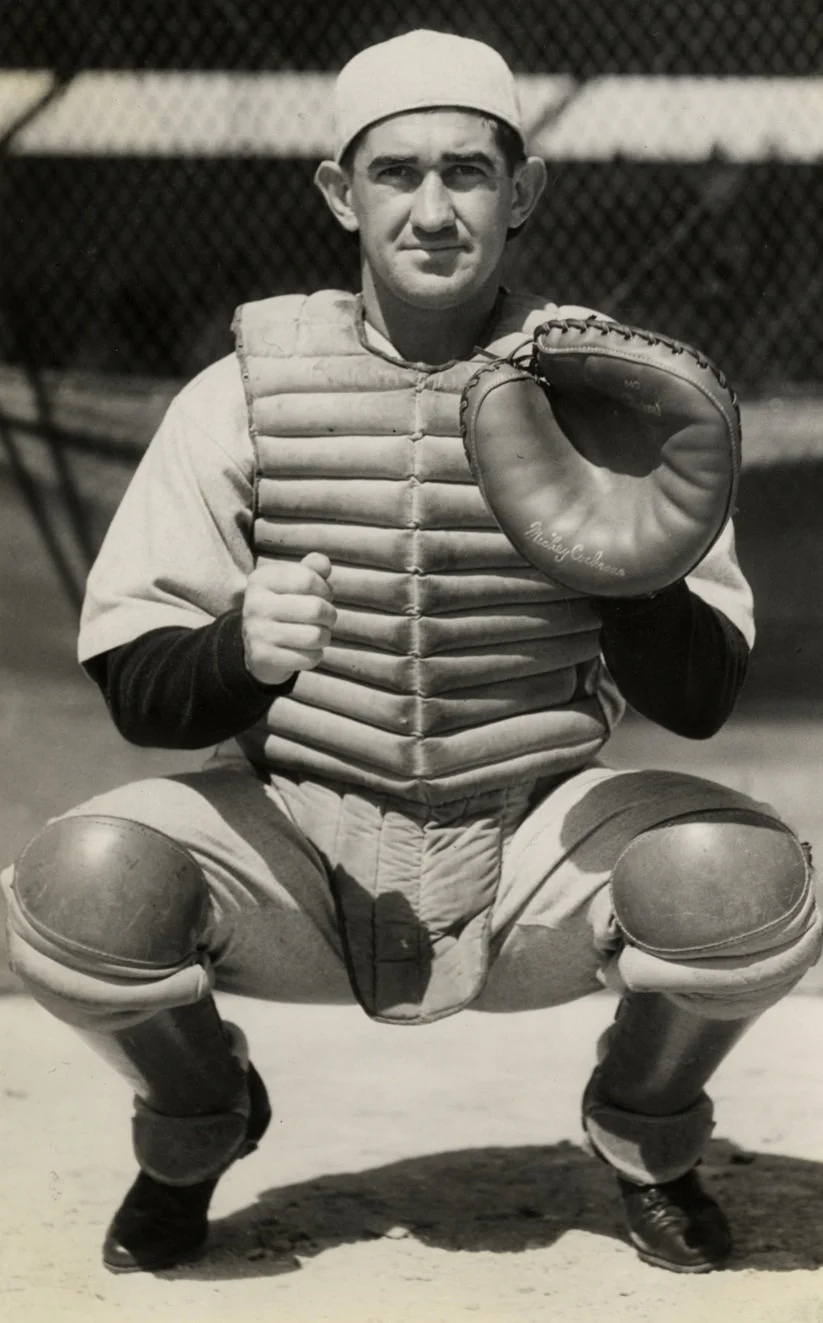

Quincy Trouppe

Quincy Trouppe was an amateur boxing champion, as well as a catcher in the Negro leagues from 1930 to 1949. He also played in the Mexican League and the Canadian Provincial League.

His teams included St. Louis Stars, Detroit Wolves, Homestead Grays, Kansas City Monarchs, Chicago American Giants, Indianapolis ABC's/St. Louis Stars, New York Cubans, and Bismarcks (aka Bismarck Churchills). He played in Latin America for 14 winter seasons and barnstormed with Black all-star teams, playing against white major league players.

He was a player-manager for the Cleveland Buckeyes, whom he led to Negro American League titles in 1945 and 1947 (he is pictured here, on the left, with Sam Jethroe). Trouppe managed the Santurce Crabbers in the Puerto Rican winter league, winning the 1947-48 season championship.

1935 Pittsburgh Crawfords

The Pittsburgh Crawfords won the Negro National League’s first half championship, and the NNL pennant in 1935, finishing the season with a 44-20-3 record in league play.

The team featured four future members of the National Baseball Hall of Fame, including Josh Gibson (who was inducted in 1972), player-manager Oscar Charleston (1976), Cool Papa Bell (1974), Judy Johnson (1975) and owner Effa Manley (2006).

1924 Kansas City Monarchs

The Kansas City Monarchs won the Negro National League pennant in 1924, finishing the season with a 57-22 record in league play. They went on to defeat the Hilldale Club five games to four in the best-of-nine 1924 Colored World Series.

The team featured three future members of the National Baseball Hall of Fame, including player-manager José Méndez (who was inducted in 2006, and was one of the first group of players elected to the Cuban Baseball Hall of Fame in 1939), Wilber “Bullet” Rogan (1998), and owner J. L. Wilkinson (2006). It also featured 1923 Triple Crown winner Oscar “Heavy” Johnson.

1930 St. Louis Stars

The St. Louis Stars won the Negro National League’s first half championship, and the NNL pennant in 1930, finishing the season with a 65-22-1 record in league play.

The team featured three future members of the National Baseball Hall of Fame, including Cool Papa Bell (who was inducted in 1974), Mule Suttles (2006), and Willie Wells (1997). Famed two-way player Ted “Double Duty” Radcliffe, who was so named because of his ability to pitch one game of a doubleheader, and catch the other, was also one of the team’s stars.

Effa Manley

Larry Doby broke the color barrier in the American league on July 5, 1947, just 11 weeks after Jackie Robinson became the first Black player in the Major Leagues.

Bill Veeck actually paid Effa Manley of the Newark Eagles, who was the Negro League team owner who had previously employed his new player.

Effa Manley co-owned the Newark Eagles with her husband, Abe. In 2006 the Special Committee on Negro Leagues elected her to the National Baseball Hall of Fame for her work as a baseball executive. As of 2025, she was the only woman inducted into the Hall of Fame.

Hall of Fame

Effa Manley’s career is a testament to her commitment to baseball and civil rights – and to her vision and dedication to creating respect for Negro Leagues baseball.

While attending a World Series game in 1932, Effa met her future husband, Abe Manley. Abe had already established his reputation in the local community as a baseball man. Together, they forged a partnership that resulted in the rapid rise to fame of the Newark Eagles, a team they owned from 1935 (moved from Brooklyn to Newark in 1936) until she sold the club to a group of investors in 1948.

As co-owner of the Eagles, Effa handled contracts and travel schedules for the Eagles, and she quickly gained recognition across the league for her ability to promote the team. Fellow owner Cumberland Posey remarked that the league could learn something from her keen sense of promotion. She also displayed personal care for the team’s players on and off the field, assisting them with jobs, serving as godparents to some, and purchasing a $15,000 bus for the team’s travel – always working to get players the best available accommodations on the road.

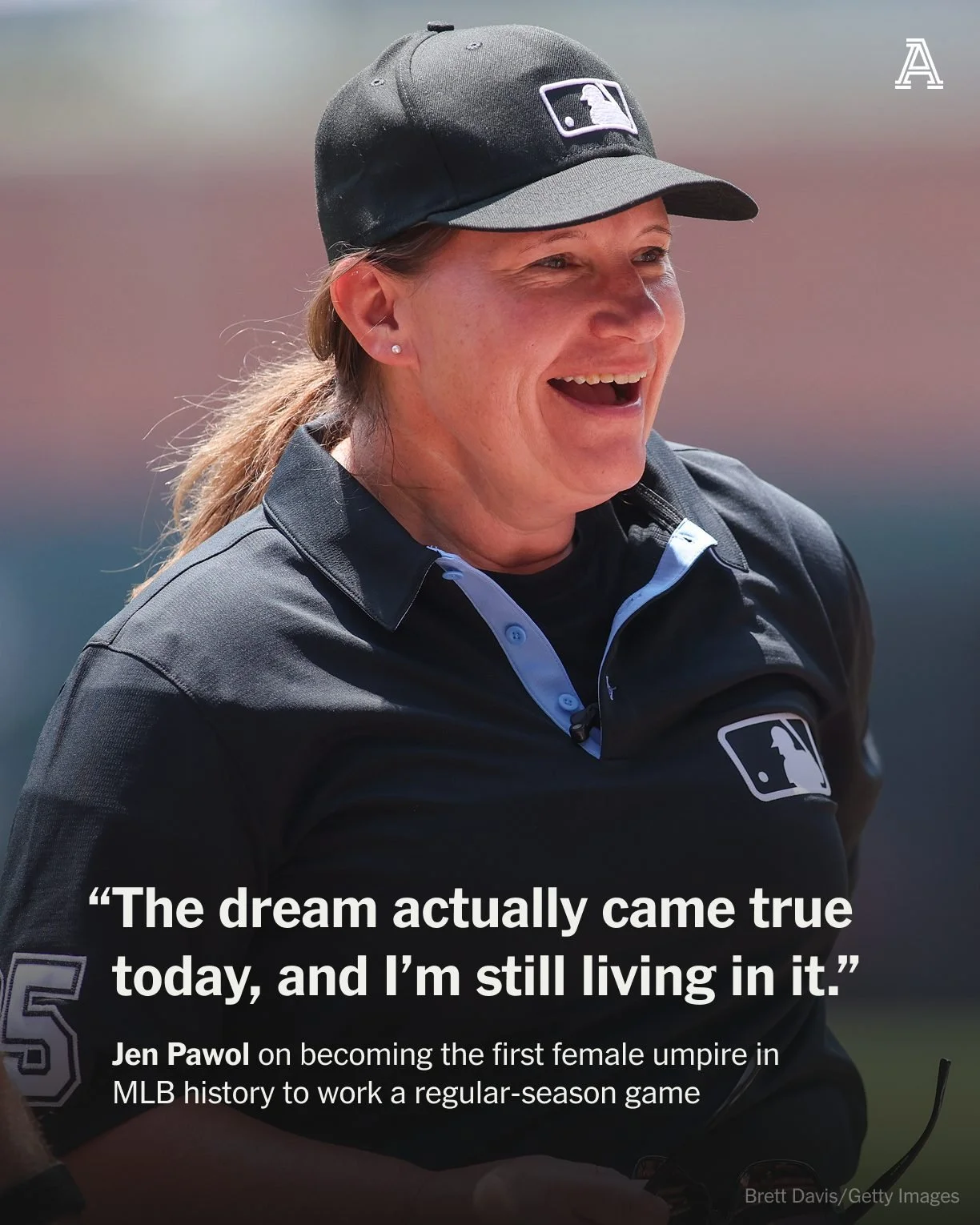

Jen Pawol

Jen Pawol became the first female Major League Baseball umpire when she debuted on August 9, 2025. She is the seventh woman to work as a professional baseball umpire.

Pawol appeared as the first base umpire in the first game of a doubleheader between the Miami Marlins and Atlanta Braves at Truist Park in Atlanta, joining crew chief Chris Guccione at second base, Chad Whitson at third and David Rackley at home plate. She was third base umpire in the second game of the doubleheader.

She continued as an umpire on Sunday, August 10, becoming the first female home plate umpire in a regular-season MLB game, in another game between the Atlanta Braves and the Miami Marlins.

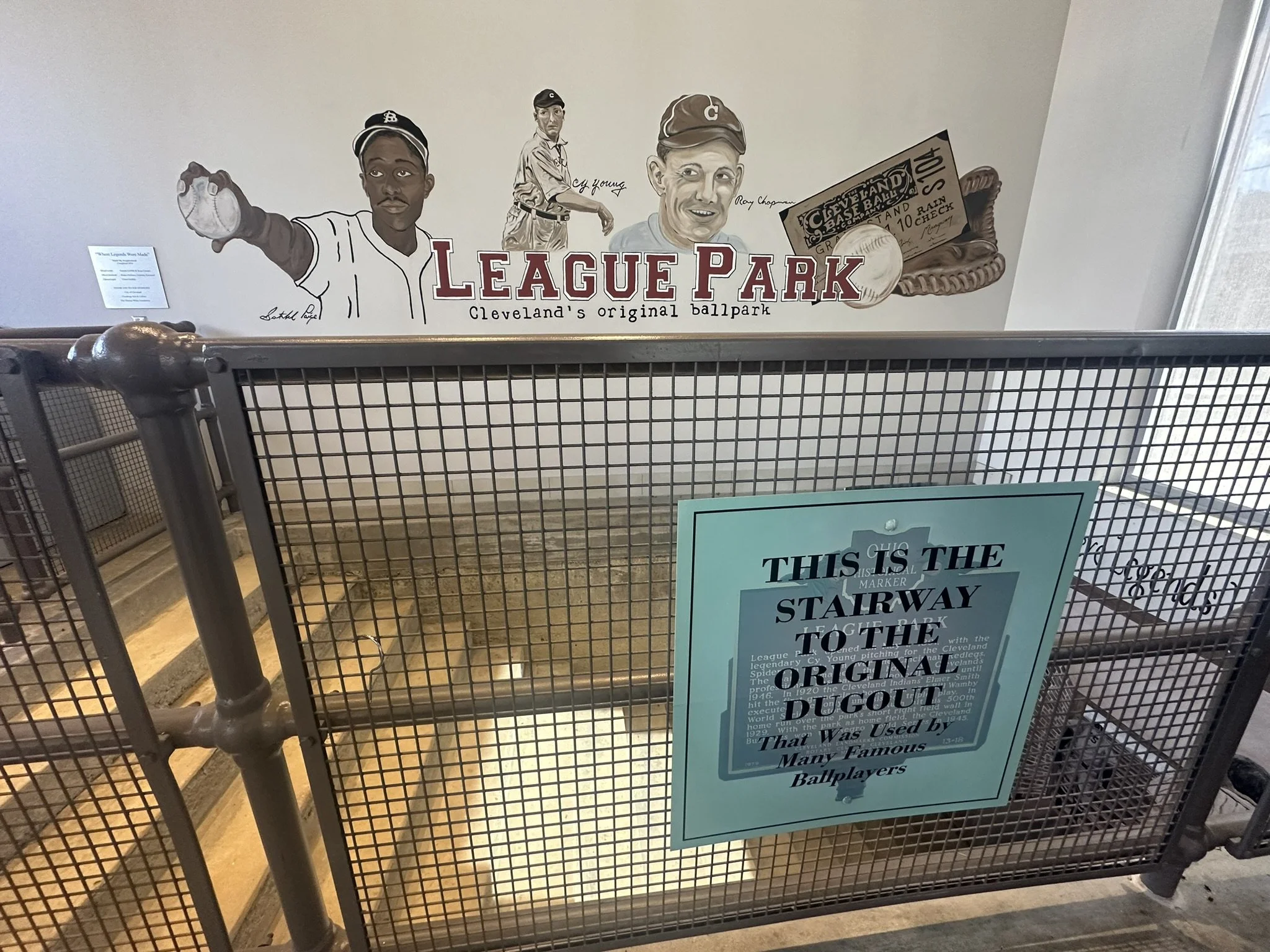

One Of Only A Few Still Standing

League Park remains significant today because it is one of only five Negro League home ballparks still in existence.

It’s a powerful thing to be able to go to the actual places where these players stood, and to walk in their footsteps.

Where They Stood

The list of players to walk down this stairwell is the Who’s Who of baseball history: Babe Ruth, Ty Cobb, Lou Gehrig, Ted Williams, Shoeless Joe Jackson, Cy Young, Bob Feller, Dizzy Dean, Jimmie Foxx. But also Negro League players like Josh Gibson, Cool Papa Bell, Buck Leonard, Ray Brown, and Jud Wilson. Even Willie Mays walked down this stairwell when he played a game at League Park on July 18, 1948.

Martin Stadium

White teams usually had their own stadiums, and often owned their own stadiums. But that wasn't a very common thing for Negro League teams.

Martin Stadium, formerly known as Lewis Park, was home of the Memphis Red Sox. During its era, the stadium was one of the few African-American-owned and operated ball parks in the country.

Robert S. Lewis, Sr., one of the pioneers in Negro baseball, built the park at the corner of Iowa Avenue and Lauderdale Street. Lewis sold the park and the team to W. S. Martin and his brothers in 1927. Before it was demolished in 1961, Martin Stadium also hosted African-American community events.

Greenlee Field

William "Gus" Greenlee, a benevolent community figure with a criminal background, built Greenlee Field on Bedford Avenue as the home of the Pittsburgh Crawfords baseball team. Greenlee, who was extensively involved in the city's numbers rackets, saw the team as an opportunity to legitimize his wealth through baseball ownership.

The presence of field lights above the stands indicates this photo was taken after September 1932.

Greatness at Greenlee

Of the many incredible games which took place at Greenlee Field over the years, my time machine game for that site may be this July 8, 1932 no-hitter by Satchel Paige.

July 8, 1932: Satchel Paige Throws First Recorded No-Hitter Of His Professional Career article by Aaron Tallent

Larry’s Time Machine Game

Pretty hard to argue against wanting to see this one in person.

Smoky and the Bandit: The Greatest Pitching Duel in Blackball History article written by … Larry Lester

Quincy Trouppe

Quincy played with the Satchel Paige All-Stars in 1946, and had some incredible stories about that tour. But he also kept everything, and was a documentarian, of sorts, taking lots of photos and even videos, keeping scrapbooks and scorecards and all kinds of artifacts from his life and career.

Trouppe was a 39-year-old “rookie” when he caught six games for the 1952 Cleveland Indians. On May 3, 1952, he and "Toothpick Sam" Jones formed the first Black battery in American League history.

It is fitting that his autobiography is titled “20 Years Too Soon.” You can buy it HERE.

This photo shows the All-Stars who accompanied Satchel Paige (top row, in hat) during his 1946 barnstorming tour. Quincy Trouppe is on the far right, wearing his camera around his neck.

Cleveland Tate Stars

The Cleveland Tate Stars were the city's representative in Rube Foster's Negro National Baseball League in 1922 and part of 1923, with offices located at 3734 Central Ave.

Owned by businessman George Tate, the team was plagued by financial problems during its short existence despite reporting decent attendance figures at their home games, and owning their own park, Tate Field. Negro National League founder Rube Foster once called the park, located E. 55th St. between Woodland and Central avenues, "one of the finest baseball stadiums owned by our people in the country."

The Tate Stars played as an independent (non-affiliated) team from 1919 through 1921, and joined the Negro National League in 1922. In their only season as a full-fledged league member, they finished last out of eight clubs with a reported 17–29 record in league play.

They returned to independent ball in 1923, loosely associated with the Eastern Colored League, but in August rejoined the NNL as an associate team, finishing with a record of 13–16–1 against all opponents. Candy Jim Taylor was the team’s player-manager.

Sam Jethroe

Dr. Layton Revel published this great piece on Sam Jethroe in 2020, but Stephanie would still like to do more research on “The Jet.”

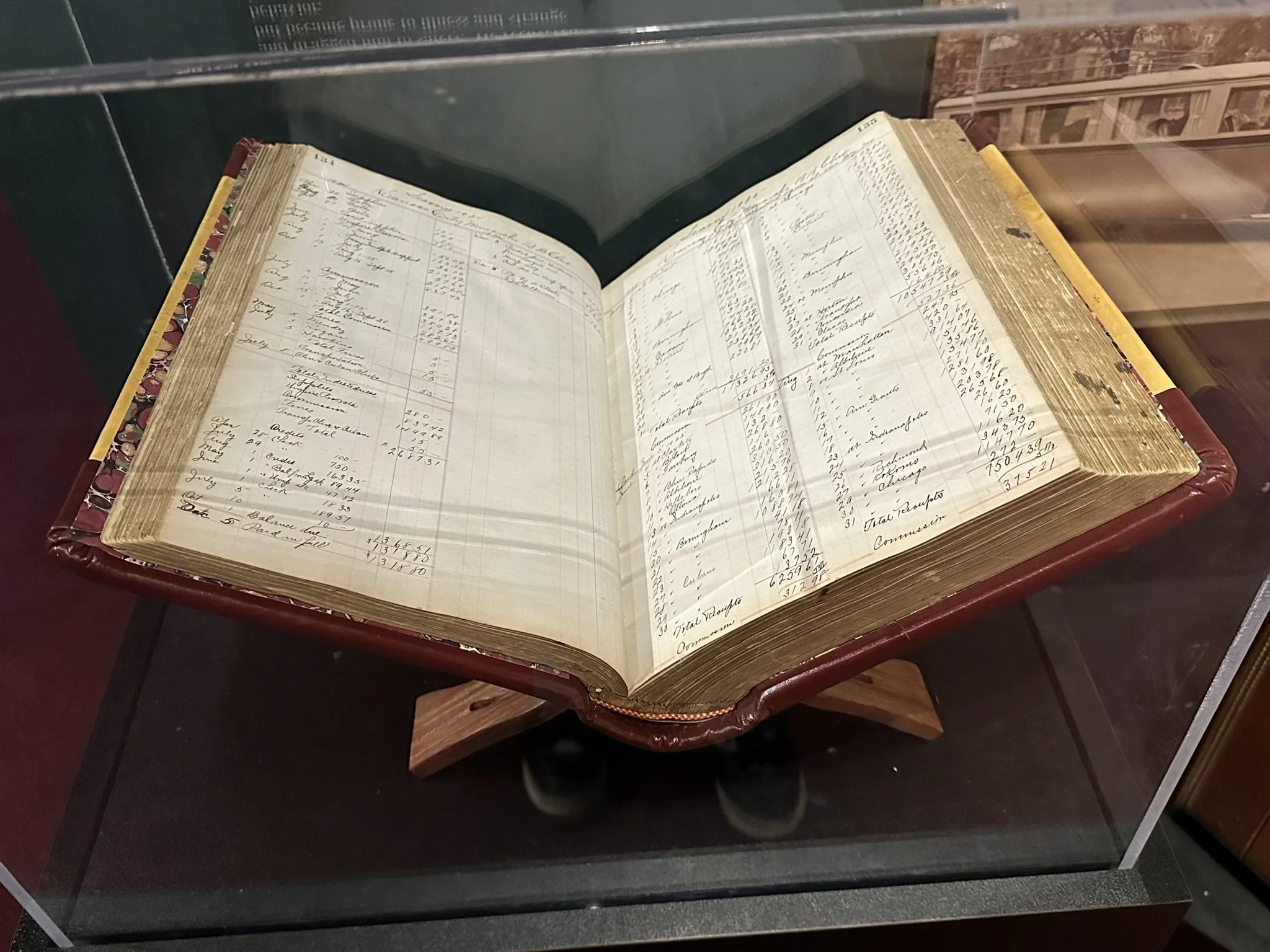

Financial Records

Thanks to historian and collector Jay Caldwell, this incredible piece now belongs to the Negro Leagues Baseball Museum in Kansas City. It is the original financial ledger of the Negro National League which was kept by Rube Foster.

Ed Bolden

Ed Bolden's first occupation in baseball was as a 28-year-old volunteer scorekeeper for a team out of Darby, Pennsylvania, under 19 year-old manager, Austin Thompson. Thompson went on to organize the Hilldale Club out of Darby in the spring of 1910.

After Thompson established the Hilldale Club, Bolden took over as owner and head of the team. Bolden transformed the team's status from amateur to professional. This aided the team in taking off financially, as the team attracted high levels of talent and scheduled games against skilled opponents. When it came to recruiting players, he would either go out and look for specific types or levels of talent, or place advertisements in local newspapers regarding open tryouts.

Ed Bolden’s Hilldale Daises in 1912

The Martin Brothers

The Memphis Red Sox played at Martin Stadium, which was owned by the Martin brothers, who owned the team. That made the Memphis Red Sox one of the only Negro League teams to own their own stadium.

A stadium owned by Blacks, that promoted Black athletics, was a unique cultural fixture in any American city - much less a major city in the segregated south.

Black Baseball’s National Showcase

Larry has written many books, but Stephanie thinks his book about the history of the East-West All-Star Game is a must-read for any fan.

When the best Black ballplayers assembled for the annual East-West All-Star games, the concentration of talent on the field was second to none. This scholarly work brings together the painstakingly assembled history of those games, reconstructed play-by-plays, and accurate statistical records.

Buy a copy of this amazing book HERE.

Baseball’s Great Experiment

In this gripping account of one of the most important steps in the history of American desegregation, Jules Tygiel tells the story of Jackie Robinson's crossing of baseball's color line.

Examining the social and historical context of Robinson's introduction into white organized baseball, both on and off the field, Tygiel also tells the often neglected stories of other African-American players - such as Satchel Paige, Roy Campanella, Willie Mays, and Hank Aaron - who helped transform our national pastime into an integrated game.

Drawing on dozens of interviews with players and front office executives, contemporary newspaper accounts, and personal papers, Tygiel provides the most telling and insightful account of Jackie Robinson's influence on American baseball and society.

Buy a copy of it HERE.

Only The Ball Was White

When Only the Ball Was White was first published in 1970, Satchel Paige had not yet been inducted into the Hall of Fame and there was a general ignorance even among sports enthusiasts of the rich tradition of the Negro Leagues. Few knew that during the 1930s and '40s outstanding black teams were playing regularly in Yankee Stadium and Brooklyn's Ebbets Field. And names like Cool Papa Bell, Rube Foster, Judy Johnson, Biz Mackey, and Buck Leonard would bring no flash of smiling recognition to the fan's face, even though many of these men could easily have played alongside Ty Cobb, Walter Johnson, Hack Wilson, Lou Gehrig--and shattered their records in the process.

In Only the Ball Was White, Robert Peterson tells the forgotten story of these excluded ballplayers, and gives them the recognition they were so long denied.

Buy a copy of it HERE.

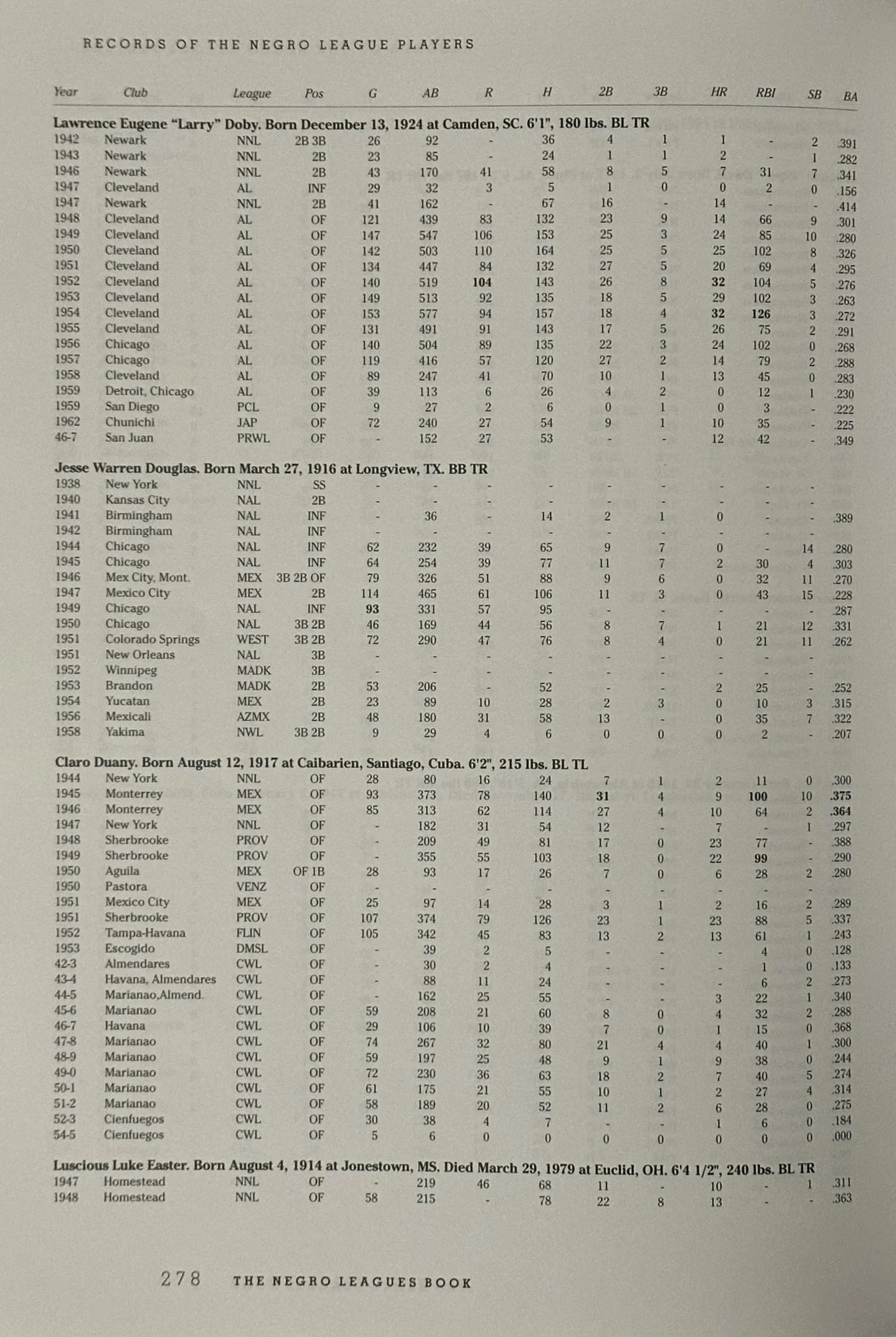

Larry’s Research

It has taken decades, but Larry’s painstaking research has allowed his player encyclopedia to be formatted the same way as The Baseball Encyclopedia, the baseball reference book first published by Macmillan in 1969.

Larry tracked down players’ heights, weights, birthdays, home towns, whether they batted left-handed or right-handed (BL or BR), and whether they threw left-handed or right-handed (TL or TR).

Here is a sample page with a couple pretty great players on it.

You can buy a copy of the updated edition HERE.

Malvin Powell

Malvin “Putt” Powell, was a pitcher in the Negro Leagues between 1929 and 1937. Powell spent his entire career with the Chicago American Giants, and was selected to play in the 1934 East–West All-Star Game.

It was only after hearing from Powell’s daughter, Malva, that Larry learned Putt’s real first name was M-A-L-V-I-N, and not M-E-L-V-I-N, as had been mistakenly written in every newspaper of the day.

Ross Davis

Ross “Satch” Davis was born on July 28, 1918 in Greenville, Mississippi. He pitched in the Negro Leagues from 1940-1947 with the Baltimore Elite Giants, Cleveland Buckeyes, New York Black Yankees, and Boston Blues.

He threw a no-hitter with Roy Campanella as his catcher as a member of the Baltimore Elite Giants against a potent Newark Eagles lineup that included Hall of Famers Biz Mackey, Monte Irvin, and Willie Wells on “Decoration Day” in 1940, which threw Larry for a loop while trying to corroborate that story. What is now known as “Memorial Day” was called “Decoration Day” from 1868 through 1967.

Davis pitched and won against Satchel Paige in 1943 and against Dan Bankhead in 1947. He played with Jackie Robinson's All-Stars in 1946, and pitched in the 1947 Negro World Series as a member of the Cleveland Buckeyes.

His career was interrupted due to his military service in World War II from November 1943 through the end of the 1945 season. During his Army service, he was awarded a Bronze Star.

Flying The Negro League Championship Flags

Larry’s current mission is trying to get each of the current Major League teams to fly the flags of the Negro League teams from their cities who previously won Negro League championships.

The Chicago White Sox are the only team to have honored a Negro League team in such a way, as of 2025. Pictured here is the Chicago American Giants flag flying at whatever the White Sox are calling their stadium this month.

A Legacy Lost

The Pirates gutted what was known as Legacy Square of its seven statues of Negro leagues ballplayers along with the associated interpretive panels which were on display at PNC Park.

As Opening Day 2015 approached, the Pirates were set to destroy the statues after having already destroyed the large Legacy Square baseball bats. Purely by coincidence, Sean Gibson (great-grandson of Josh Gibson and Executive Director of the non-profit Josh Gibson Foundation) was offered a chance to rescue the statue of his great-grandfather.

With insufficient storage or transportation, Gibson initially balked at the offer, instead suggesting the statues be redistributed throughout PNC Park, but once he realized the urgency of the situation, Gibson informed the Pirates that he would take the Josh Gibson statue – as well as the six others.

Integrated Crowds

Depending on the stadium, sometimes white fans were allowed to intermingle with Black fans.

Photo by Frank Russell Hightower, courtesy of Craig Britcher

Segregated Crowds

In some cases, such as at Rickwood Field in Birmingham, Alabama, there was a dedicated “Black” section during Birmingham Barons games, while the rest of the stadium was open to white fans.

So when the Birmingham Black Barons would play at Rickwood, the Black fans flipped the script, forcing white fans to sit in the uncovered seats beyond the right field fence, the same way they were made to during white games.

If anyone tried to buck the system, there was trouble.

Scorebooks

Scorebook from the Hilldale Club of the Eastern Colored League, dated September 18, 1926.

Photo courtesy of Gary Ashwill

More Scorebooks

Scorebook from a game between the Baltimore Elite Giants and New York Cubans in Baltimore on June 12, 1942.

Photo courtesy of Gary Ashwill

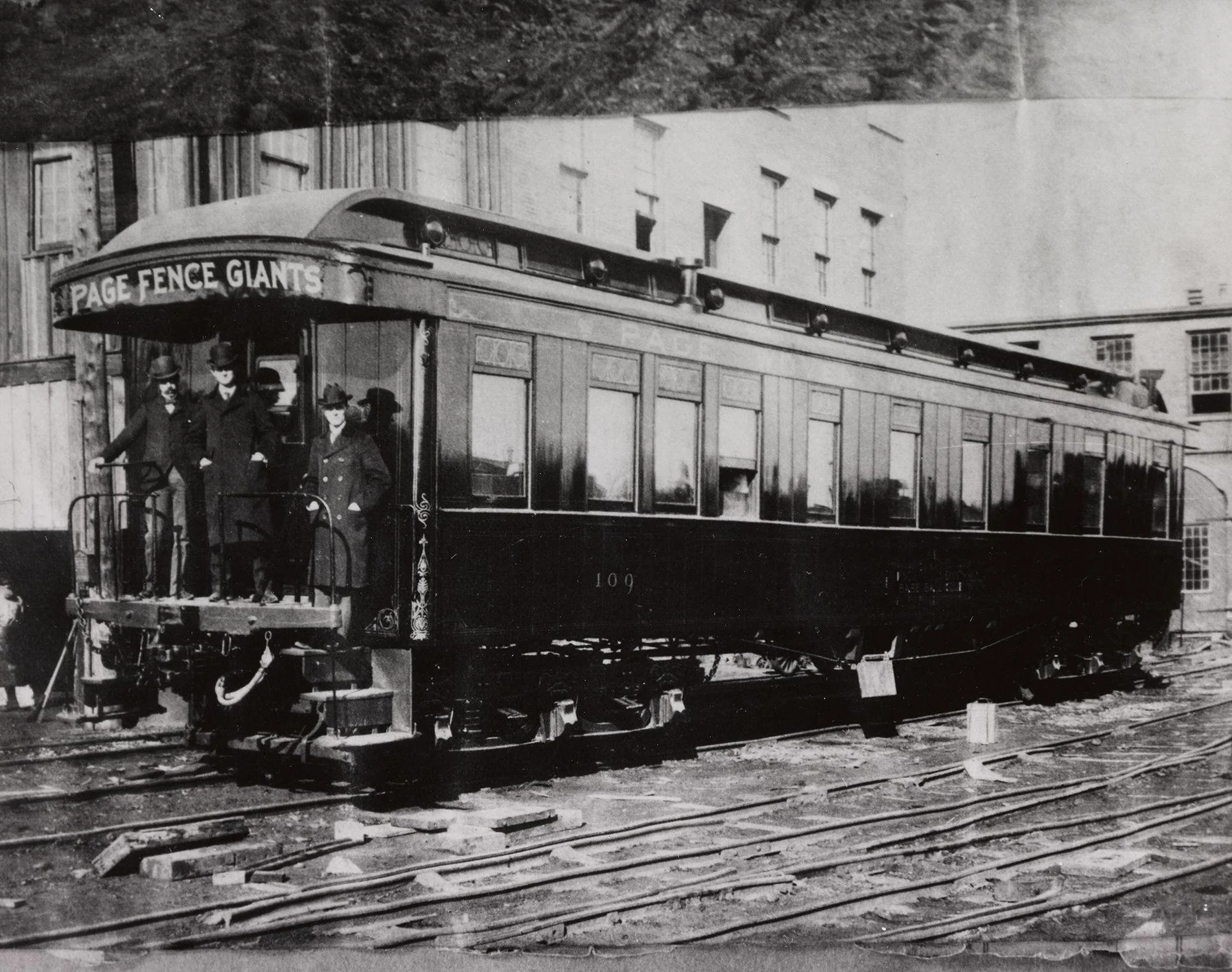

Train Travel

John W. Jackson Jr., better known as “Bud Fowler,” made his pro debut in 1878 in the International Association. He is believed to be the first Black player to play pro baseball.

Fowler played for – among other teams – the Page Fence Giants, a top pre-Negro Leagues team of the 19th century that also featured future Hall of Famer Sol White. The team traveled by train in a car that advertised the team.

Photo courtesy of the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum

Follow Stephanie Online

If you think this episode has been worth even one dollar, please use one of the QR codes you see here to make a donation in any amount on your preferred payment app. If you would rather make a donation another way, you can email me.

The Field of Legends at the Negro Leagues Baseball Museum in Kansas City, Missouri.

NLBM With My Mom

Ever since my first trip to the Negro Leagues Baseball Museum, my mom has wanted to visit it for herself. I took her there in July of 2025 so we could finally cross it off her list.

A Live Event

Larry and Stephanie were a joy to have on the show, and made it so easy for me to record this conversation in front of a live audience, something I had never done before.

Bill Veeck

Not everyone may have agreed with every decision Bill Veeck made, or the way he went about doing things sometimes, but you can’t argue with results. This plaque proves his lasting impact on the game, and on society.

Bill Veeck was inducted into the National Baseball Hall of Fame in 1991.

Bill’s son, Mike, who has been a lifelong baseball showman in his own right, was our guest for Episode 4 of Season 3. You can listen to that episode HERE.

Wendell Smith

In one sense, the story of baseball’s integration can be traced to a diamond in Detroit in 1932. Wendell Smith was an 18-year-old pitcher in a playoff game. He threw a shutout masterpiece. His team won 1-0, in extra innings. Afterward, Wish Egan, a scout for the Detroit Tigers, signed the losing pitcher, who was white, but said he couldn’t sign Smith because he was black.

“Wendell went home and cried,” author Michael Marsh said. “That helped spur his activism.” From that moment, Smith devoted himself to challenging baseball’s racial barriers.

While working for the Pittsburgh Courier in 1942, Smith wrote, “Major League Baseball is perpetuating the very things thousands of Americans are overseas fighting to end, namely, racial discrimination and segregation.”

42

Andre Holland plays sportswriter Wendell Smith in the movie 42.

“The story is that Branch Rickey hand-picks Wendell Smith to sort of follow Jackie Robinson around and teach him about the politics of the time and keep him out of trouble. And in exchange for that, he gets unprecedented access to the team,” Holland said.

Photo courtesy of Birmingham News/Bob Carlton

Turkey Stearnes

Having been to the Hall of Fame after becoming a much more informed student of the Negro Leagues and its players, it’s easier to have an image come to mind when certain names are mentioned.

That was the experience my mom had when Turkey Stearnes’ name was brought up during this discussion.

Sam Allen

Sam Allen is a former Negro League player who spent time as a member of the Kansas City Monarchs, the Raleigh Tigers, and the Memphis Red Sox. He led the Negro American League in runs scored in 1957, helping the Monarchs win the championship.

Sam was our guest for Episode 2 of Season 3. You can listen to that episode HERE.

Jackie Mitchell

If you’re anything like my mom, the more you learn about Kenesaw Mountain Landis, the more you’ll despise him.

Female Umpires

Perry Barber has been a professional and amateur baseball umpire since 1981.

Perry was our guest for Episode 6 of Season 2. You can listen to that episode HERE.

During our discussion, Perry brings up women like Eleanor Engle and Maureen Galvin, who were kept from participating in professional baseball games by Ford C. Frick, following the tradition of Kenesaw Mountain Landis of not allowing women in baseball.

Phil Dixon

Phil S. Dixon (pictured here, left) is an author, public speaker, researcher and historian, focusing on the Negro Leagues for the past 40 years.

Phil was our guest for Episode 4 of Season 1. You can listen to that episode HERE.

Jay Valentine

Jay Valentine patrolled center field in 1977 and 1978 for the Indianapolis Clowns, the last of the Negro League baseball teams.

Jay was our guest for Episode 6 of Season 4. You can listen to that episode HERE.

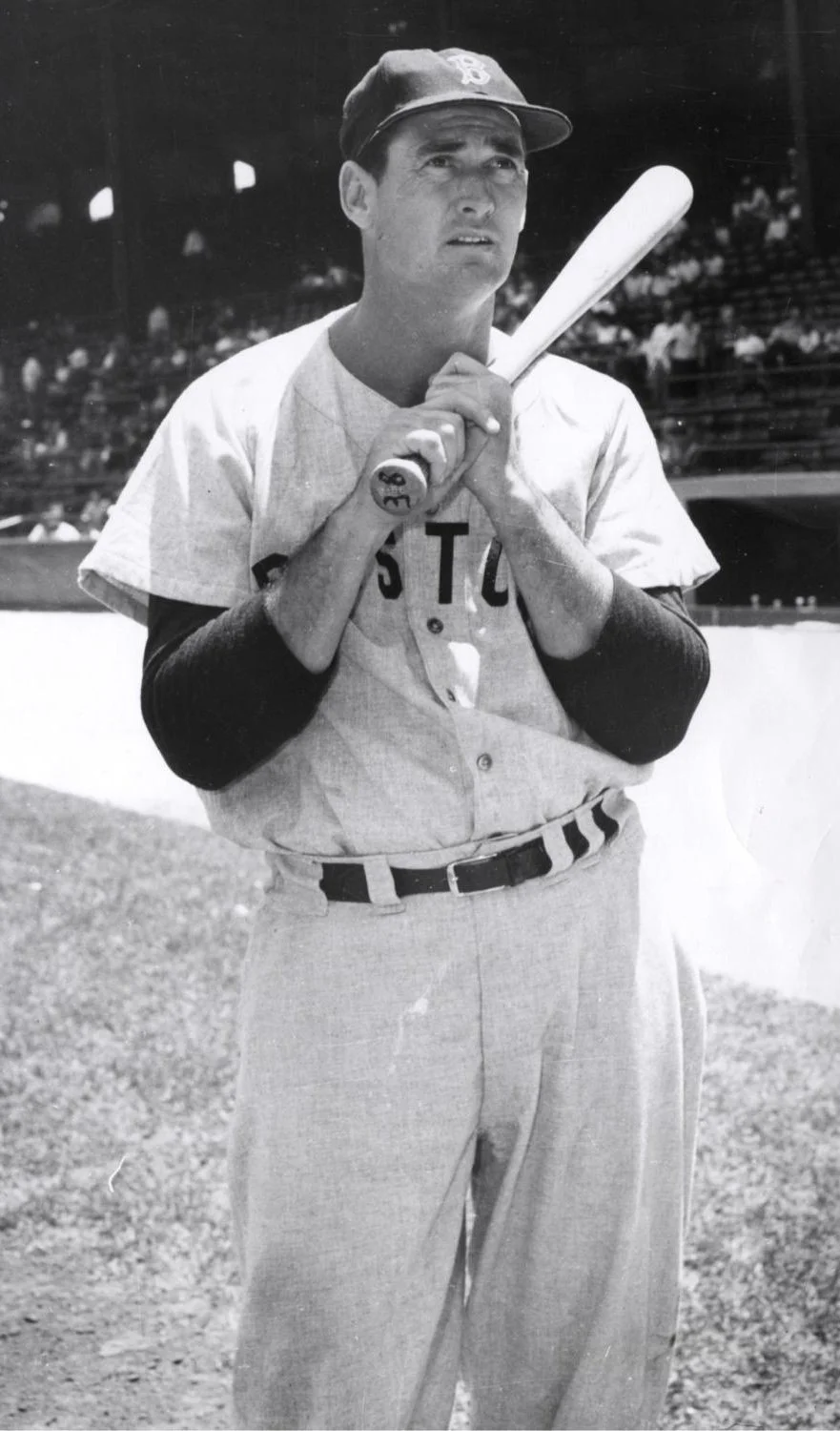

Ted Williams

As Ted Williams ascended to baseball superstardom, he made a conscious effort to distance himself from his Mexican roots. At the time, racial discrimination was rampant in the United States, and many Mexican Americans faced prejudice both socially and professionally. Williams, keenly aware of how this could impact his career, chose to identify solely as an Anglo-American.

Despite his public silence, hints of his background occasionally surfaced. His mother’s maiden name, Venzor, was well known, and some journalists speculated about his heritage. But Williams rarely addressed the subject, instead focusing on his pursuit of baseball excellence. He wanted to be known for his bat, not his background.

In March of 1946, Williams was offered $500,000 to quit the Red Sox and play for Havana in the Mexican League. The Splendid Splinter refused the offer, but a handful of other white Major Leaguers and plenty of Negro League players would accept the invitation to play in the Mexican League. By 1940, there were 63 African-American players in Mexico.

The Best of The Best

Just some of the awards former Negro League players won in the white Major Leagues within the first 15 years or so after integration:

- Jackie Robinson won Rookie of the Year in 1947, and NL MVP in 1949

- Roy Campanella won NL MVP in 1951, 1953, and 1955

- Don Newcombe won Rookie of the Year in 1949, and won the NL MVP and Cy Young Awards in 1956

- Sam Jethroe won Rookie of the Year in 1950

- Willie Mays won Rookie of the Year in 1951 and won the NL MVP in 1954 and 1965

- Joe Black won Rookie of the Year in 1952

- Junior Gilliam won Rookie of the Year in 1953

- Henry Aaron won NL MVP in 1957

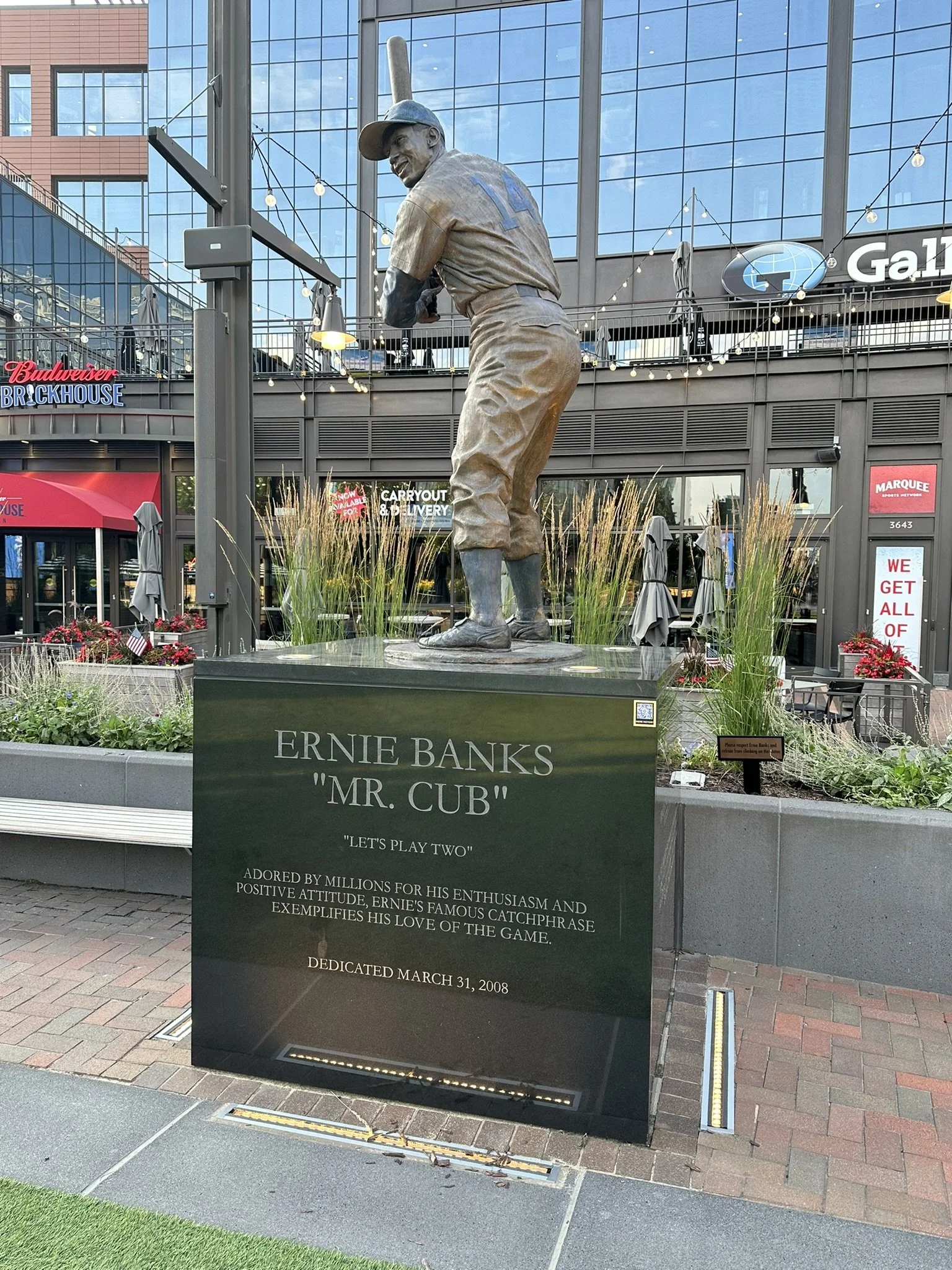

- Ernie Banks won NL MVP in 1958 and 1959

- Elston Howard won AL MVP in 1963

Frank Robinson